Image: The coral reef at Pulau Satumu, home to Raffles Lighthouse, is a prime example of a turbid yet thriving ecosystem. The island’s orientation and shifting tides generate consistently strong currents across its reefs, says Assistant Professor Kyle Morgan, who led the study. (Credit: Kyle Morgan)

Image: The coral reef at Pulau Satumu, home to Raffles Lighthouse, is a prime example of a turbid yet thriving ecosystem. The island’s orientation and shifting tides generate consistently strong currents across its reefs, says Assistant Professor Kyle Morgan, who led the study. (Credit: Kyle Morgan)

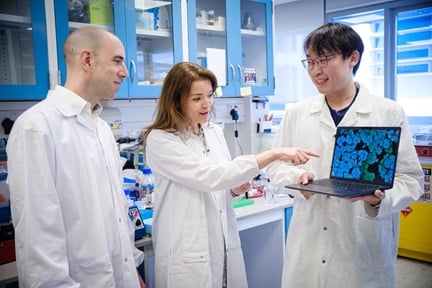

A recent study by scientists from NTU Singapore, has shown that high levels of terrestrial sediments – which are particles eroded from land surfaces – in seawater can significantly impede coral reef growth and hinder reef recovery following coral bleaching.

Suspended in seawater, these fine sediment particles comprise mud, silt, and organic matter, all of which reduce the penetration of sunlight, which is essential for coral photosynthesis and growth and can smother corals on the seafloor.

Conducted at six coral reef sites in southern Singapore, the study showed a clear link between increased sediment levels and decreased coral cover.

Coral cover on reefs with higher sediment content were also less likely to recover after a coral bleaching event.

The accumulation of mud sediments not only hamper coral growth but also weaken reef structures and reduce the amount of sand generated by reef organisms, making coastlines more susceptible to erosion.

Co-author of the study, Nanyang Assistant Professor Kyle Morgan from NTU’s Asian School of the Environment and the Earth Observatory of Singapore, explained: "As coastal development in the region increases, greater amounts of mud are being washed into the sea during rainfall events. Our study finds that even corals which have adapted to living in murky waters will struggle to grow when there is too much sediment."

The study’s first author, Ms Marlena Joppien, a PhD student from NTU’s Asian School of the Environment and the Earth Observatory of Singapore, added: "It is important for countries to have good environmental planning, which can help reduce sediment runoff and mitigate the impacts on coral reefs. At the same time, our study can inform marine scientists to carefully choose where they seed new corals for conservation since clearer waters will give corals a better environment to thrive and grow."

For instance, Singapore has been proactive in coral restoration, with initiatives led by the National Parks Board (NParks) and local researchers.

Efforts include coral nurseries, artificial reef structures, and relocation projects aimed at bolstering coral resilience.

The study's findings offer valuable insights to optimise these initiatives by highlighting the various factors in marine environments where corals are more likely to thrive.

Notably, projects like the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park serve as sanctuaries for marine biodiversity.

Enhancing coral health in such areas will help to ensure that healthy coral reefs can continue to act as natural barriers against waves and storms while contributing to sand production that replenishes beaches and coastlines.

Beyond Singapore, the research provides insights for other coastal nations facing similar challenges.

By managing coastal development and sediment runoff effectively, countries can maintain robust coral reefs that offer essential services like shoreline protection and support for marine life.

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation, Singapore (NRF), through the NRF Fellowship scheme, which funds promising early-career researchers engaged in impactful scientific endeavours.

Image: The coral reef at Pulau Satumu, home to Raffles Lighthouse, is a prime example of a turbid yet thriving ecosystem. The island’s orientation and shifting tides generate consistently strong currents across its reefs, says Assistant Professor Kyle Morgan, who led the study. (Credit: Kyle Morgan)

Image: The coral reef at Pulau Satumu, home to Raffles Lighthouse, is a prime example of a turbid yet thriving ecosystem. The island’s orientation and shifting tides generate consistently strong currents across its reefs, says Assistant Professor Kyle Morgan, who led the study. (Credit: Kyle Morgan)