Student Profile: Up Close & Personal with NTU Students’ Union President

| By Sanjay Devaraja, Editor, LKCMedicine's Redefine Newsletter |

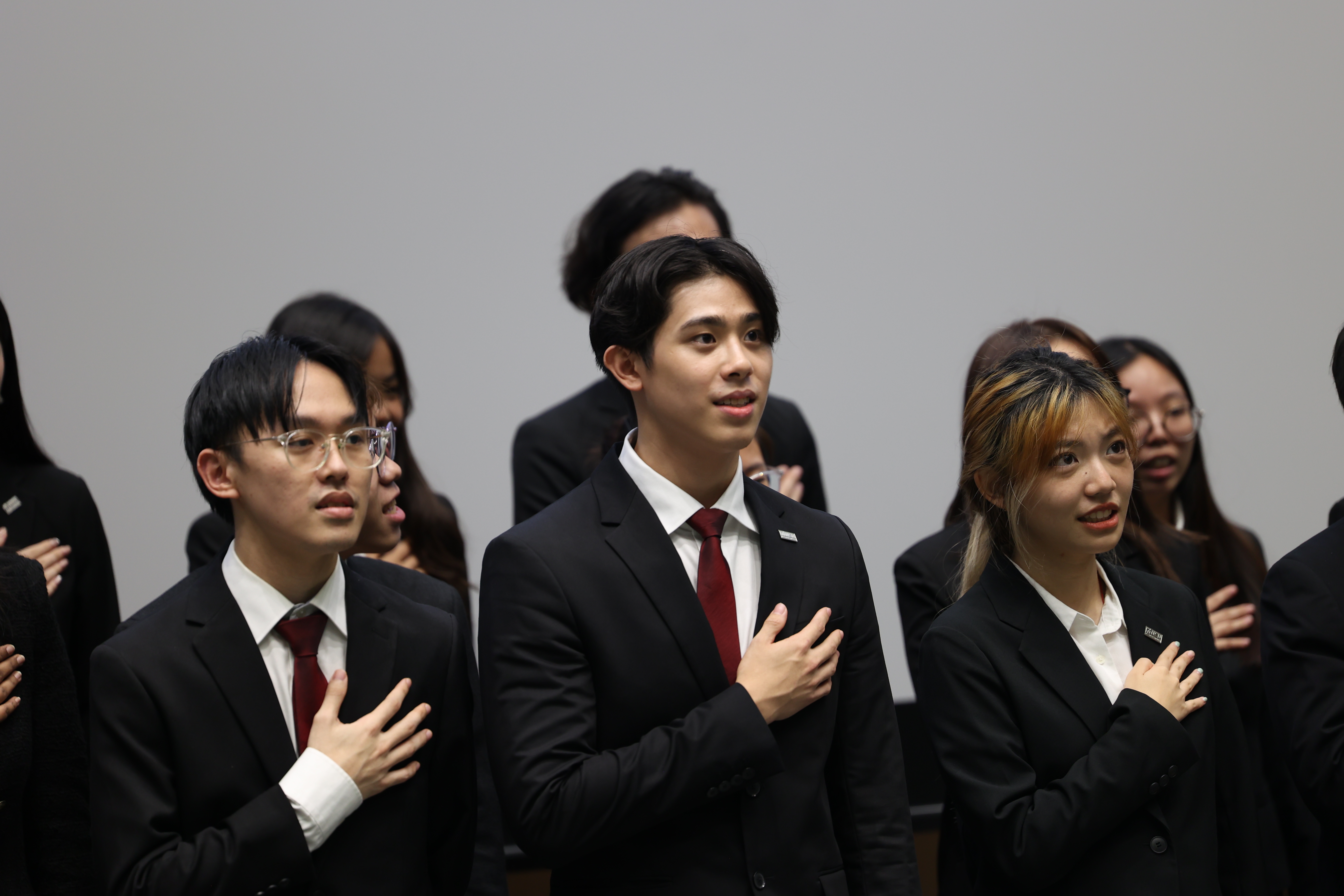

Edison Ng Wei Long is a Year 4 student at LKCMedicine and currently serves as President of the NTU Students’ Union (NTUSU). Outside of NTU, he also chairs this year’s initiatives under the Inter-University Network (IUN), working with student leaders across Singapore’s Autonomous universities on issues like mental health and redefining success.

At LKCMedicine, Edison previously served as Publicity Director of the Preventive Medicine and Public Health Student Interest Group (SIG) and was the Dinner & Dance (DnD) Head in his first year, organising the first DnD post-COVID. He is also part of the Academic Committee, and hosted the bridging programme for incoming M3 students. Academically, he is passionate about preventive medicine and genomics.

Service has always been at the heart of Edison’s journey. He was part of Project Songkeum, an overseas community initiative at LKCMedicine in Cambodia, offering health screenings and vocational training to the rural community. He also volunteers with the Bone Marrow Donor Programme and taught art at Sunbeam Place @ Children’s Society, supporting children who have experienced abuse or neglect.

Outside of work and school, Edison enjoys painting and writing poetry. With this passion for human connection and creativity, we speak to Edison to learn more about his motivations, experiences, and purpose.

As President of the NTUSU, what has been your proudest achievement so far, and what challenges have you faced in representing such a diverse student body?

My proudest achievement has been leading the Union with a renewed sense of purpose – to empower students to grow intellectually, emotionally, and socially. That belief became our North Star and shaped the major initiatives we pursue.

One of our milestones is launching U-Care – NTUSU’s first month-long campaign focused entirely on student wellbeing. Instead of focusing on mental health talks or wellness booths, the initiative redefines wellbeing as something proactive and communal. We created opportunities for students to engage with a supportive community through a diverse array of events held throughout the month – from sports and art activities to casual movie nights.

But more importantly, we recognise that our students’ wellbeing is deeply affected by structural factors. So, we advocated for institutional support like protected break periods and a more compassionate attendance policy, to ease academic strain and reduce burnout. After months of proposals, presentations, and countless consultations with students, we finally got NTU Administration to agree to almost all our proposals.

Representing such a large and diverse student body across 17 schools with vastly different curricula and cultures is never easy. But we made it a point to listen widely. We rallied student leaders from every single school, held many consultations, and engaged ground feedback sessions to make sure these proposals were reflective of real student experiences.

One of the most significant challenges was also bringing university leadership onboard. Institutional change is slow but understandably so. Rallying institutional support for structural changes require persistent engagement and a shared language of trust. We were able to show that our proposals reflected the collective student voice, hence that trust translated into action.

That, to me, was the most meaningful outcome – not just the changes, but also seeing students and university leadership share ownership of building something better, together.

How has your experience chairing the Inter-University Network (IUN) shaped your perspective on student mental health?

Chairing the Inter-University Network this year allowed me to collaborate with student leaders from all six local universities. Together, we engaged in dialogues that challenged us to reflect deeply on what students truly need today. A recurring theme was the pressure to succeed—not just academically, but also the underlying urge to pursue internships or start-ups simply because “everyone else is doing it.”

We gathered students at LKCMedicine’s Clinical Sciences Building and posed a simple yet powerful question: “What is important to you?” For many, it was the first time they had paused to consider this. They realised they had been striving for goals set by others, running a race they never chose.

That question prompted profound reflection, even for myself. Around that time, I came across a quote: “No price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.” The words resonated deeply, reminding me how rare and valuable it is to chart one’s own course. Pursuing medicine is a conscious choice for me – a path I own. The quote reinforced my belief that every decision to follow our own compass, rather than the crowd, is an act of courage that can inspire others.

My vision is to help students discover their personal compass and foster a culture where young people feel empowered to define success on their own terms. This is what gives meaning to our work.

To advance this vision, we are launching a nationwide survey and organising roadshows across all six universities. We have also secured a platform at MCCY’s SG Youth Policy Forum to amplify this message and rally support. Our hope is to spark a broader movement—one where everyone embraces their agency to define success for themselves, becoming catalysts for change within their families, communities, and society as a whole.

Can you tell us about your involvement with the Bone Marrow Donor Programme and what you would say to encourage others to volunteer?

During COVID, I worked with the Bone Marrow Donor Programme (BMDP) to organise an online donation drive, raising awareness and recruiting new potential donors even when in-person outreach was impossible. Once restrictions eased, I helped coordinate an in-person drive where we guided students through the swab process and shared stories of patients waiting for a match.

What struck me most was the profound impact a single registration could have – matching is incredibly rare, and you might be the only person in the world who fits a patient’s genetic profile. I encourage others to volunteer, because you don’t need medical training to save a life – just the willingness to step forward. Even if you’re never called, for one person out there, you could be the reason they get a second chance.

What was your experience teaching art at Sunbeam Place, and how did it influence your views on supporting vulnerable communities?

I was roped into teaching art at Sunbeam Place after casually posting a drawing I did on Instagram. My teammates, Sean and Cheng Yat, saw it and asked if I'd be willing to teach. I said yes, not knowing it would become such a meaningful experience. I went in thinking I was there to give. But I realised I was also receiving, through their laughter, and the way they found joy in the smallest things. That's when I learned I wasn't there to 'help' them! We were just people creating beautiful art together.

Medicine is, as you say, ultimately about people. Can you share a story of a person you met who profoundly shaped your journey?

During my fourth year, I had my first experience in palliative care at Assisi Hospice – a setting very different from the diagnostic, treatment-focused approach I was trained in during the first three years of medical school. There, I met a woman in her 60s living with advanced cancer. She had been given three months to live. What struck me most was how happy she seemed to be in the hospice. It almost caught me off guard. After all, I hadn’t met many patients who smiled so genuinely while speaking about dying.

I listened as she shared her diagnosis and described how, in the early stages, she fought hard – undergoing chemotherapy, hospitalisations, and countless blood tests. But when the disease returned and her prognosis changed, she made a conscious decision: she would not spend her final months fighting. She spoke about her children and expressed gratitude for the chance to be at Assisi Hospice. Despite her illness, she radiated a profound sense of peace and thankfulness.

That experience deepened my understanding of what it truly means to walk this path as a doctor. It revealed that medicine is not merely about prolonging life but about enriching it – walking alongside people through their most difficult moments and helping them find meaning. This patient taught me that the purpose of medicine goes beyond science; at its core, it is about people and their stories, and the importance of honouring those stories at every stage of life.

How do you balance your academic, leadership, service, and personal interests, and what advice would you give to students seeking similar balance?

Balance, to me, isn’t about being balanced. Ironically, balance is being clear on what matters most in each season and communicating it to the people around you. When you’re clear on your priorities, it becomes easier to let go of the guilt that often comes with feeling like you’re not doing enough.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is to lean on teammates. Trusting others, asking for help, and building systems of support makes everything more sustainable. I also try to make time for people, even when things get busy. Whether it’s a late-night supper, or a short walk after classes, these are the moments that kept me going. And over time, I’ve realised that balance doesn’t always mean strict boundaries between academics, CCA, and personal life. Sometimes, you can blend both. In fact, some of my closest friendships were formed through the work itself. Dominic and I worked together for four years. What started as project meetings slowly turned into long conversations about life, and now he’s one of my closest friends. The work brought us together, but the shared experience is what deepened the bond.

So, if I had one piece of advice, it would be this: don’t chase the perfect schedule. Instead, be clear and intentional, stay flexible and don’t feel guilty if things feel messy.

What are your aspirations for your final year in medical school and beyond?

My aspiration is simple: to grow into the kind of doctor I would want to care for my own family. The kind of doctor who would sit down when talking to my grandmother and who would explain things clearly to my anxious mother.

One of the things I’m most looking forward to is my upcoming medical elective in London, where I’ll finally get the chance to observe neurosurgery which is a field I’ve long been curious about but haven’t had exposure to in Singapore. It’s a chance to learn not just from a different specialty, but from a different system, and to see how medicine is practiced in another part of the world. Back in school, I also hope to mentor juniors and pass on the lessons I’ve received, just as others have done for me.

Looking ahead, I see myself exploring roles that combine clinical care with a strong focus on the patient experience, whether it means improving how care is delivered. I believe healthcare is as much about people and processes as it is about medicine, and I hope to help shape systems that are more compassionate and human centered.

Ultimately, I want to keep growing into someone who listens deeply and never stops learning in service of those I care for.

What are your hobbies? How do you unwind when you’re not in School?

I paint and write poetry. These are two things that help me slow down and make sense of thoughts that don’t always fit neatly into words. I also train at the gym around four times a week. Beyond that, I enjoy spending time with friends.