Student Profile: From Lab to Liver: Fiona Chen’s Award-Winning Research

| By Sanjay Devaraja, Editor, LKCMedicine's Redefine Newsletter |

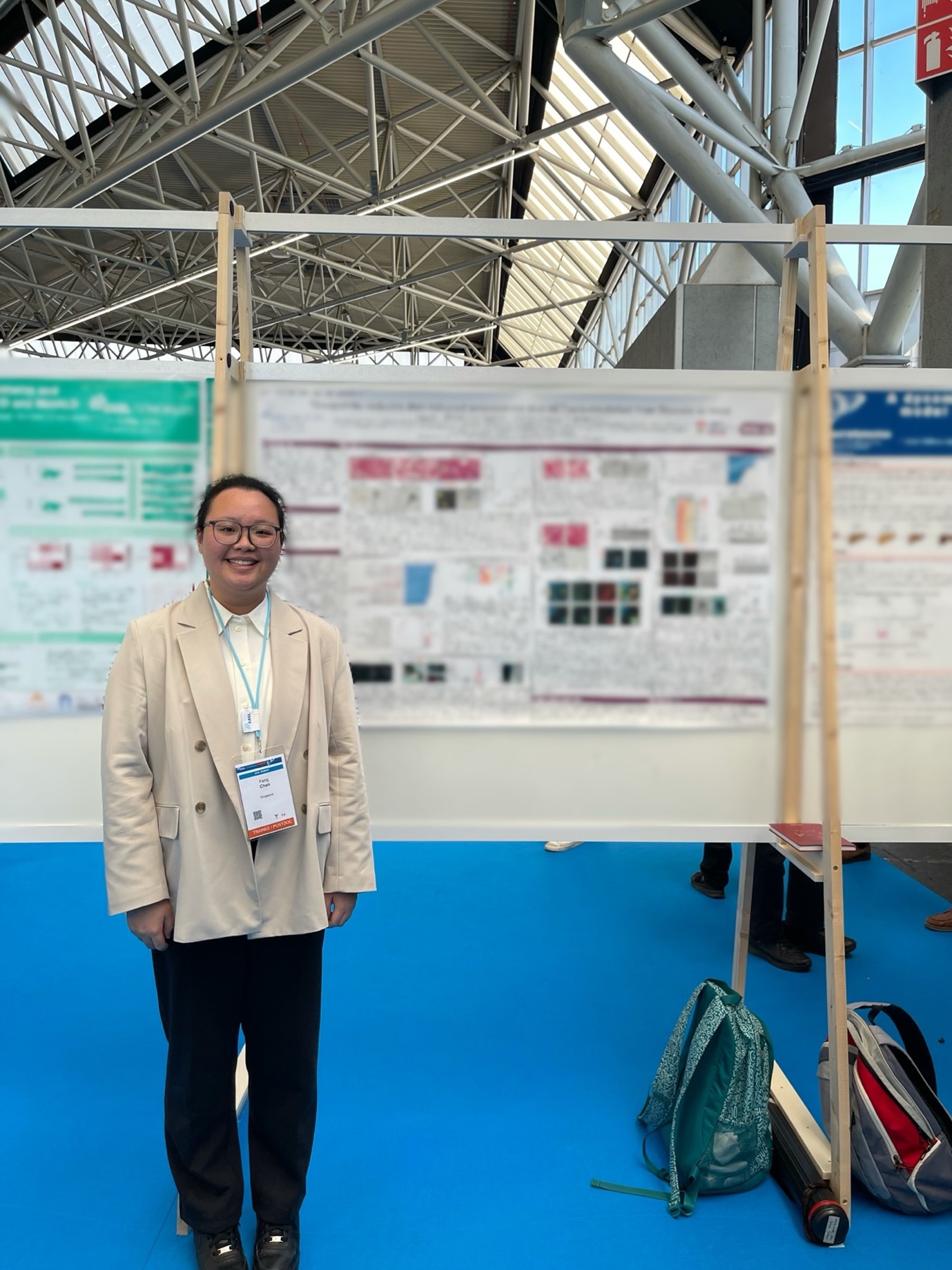

Named one of the Best Young Investigators out of more than 2,500 abstracts for the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2025. Awarded Full Bursary for Trainees and Postdoctorates by EASL. Presented a poster at a Congress in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

And a key member of LKCMedicine’s Nanyang Assistant Professor Chistine Wong’s lab that seeks to unveil a novel mechanism of how NETosis contributes to liver fibrosis and highlighted an exciting opportunity of repurposing a latest anti-diabetic drug for liver fibrosis in a non-diabetic context. And the accolades go on, for Fiona Chen, a final-year PhD candidate at LKCMedicine.

We speak to Fiona on her PhD journey, the inspiration behind her research, and the impact she hopes her findings will have on the future of liver disease treatment.

Tell us about yourself and how has your experience been like at LKCMedicine.

I am a final-year PhD candidate in Nanyang Assistant Professor Christine Wong’s Lab. My PhD project focuses on examining whether and how neutrophils are activated and promote scar formation (fibrosis) in the liver. Given the limited FDA-approved therapies for liver fibrosis, which can become irreversible at advanced stage (cirrhosis), I also explore novel treatments aimed at suppressing pathogenic neutrophil responses, thereby reducing fibrosis progression and enhancing liver recovery. LKCMedicine actively supports graduate student development through conference travel grants, enabling us to present our studies at international meetings at least once during our candidature and gain valuable feedback. Furthermore, the collaborative culture here also facilitates first-hand knowledge exchange. I always have the opportunity to discuss with domain experts in different fields and obtain valuable input for my project.

How has your experience in Nanyang Assistant Professor Christine Wong’s lab shaped your research journey?

Working in Nanyang Assistant Professor Christine Wong's Lab is an incredibly enriching experience that allows me to progressively expand my scientific capabilities. Through my PhD, I have not only acquired technical expertise across diverse methodologies but also developed critical skills in troubleshooting and planning sensible experiments. Besides, I also have the chance to participate in the lab’s external collaborative projects, working closely with engineers and clinicians and approaching problems from diverse perspectives. I am particularly grateful to be in such a supportive lab. We actively share knowledge, overcome technical hurdles together, and exchange ideas to improve each other's projects. Beyond research, we also build friendships. While in research there are always challenging moments, having such a supportive and inspiring team spirit transforms obstacles into opportunities for growth.

For readers unfamiliar with the term, could you explain what NETosis is and why it is significant in liver disease research?

NETosis is a form of neutrophil death characterised by the release of web-like structures composed of chromatin and toxic proteins. These structures, called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), were initially discovered for their role in trapping and killing bacteria. Cumulating evidence has soon shown that NETs can also form in diseases and conditions without infection, causing damage to tissues and organs. NETs are known to have active roles in the development and progression of many diseases, including complications of metabolic disorders. In liver injury, neutrophils massively migrate into the liver and become hyperactivated. Investigating whether NETosis plays a role in liver disease progression and identifying the upstream trigger of NETosis could reveal novel therapeutic strategies from the angle of inflammation. By preventing these harmful webs from forming in the first place, we may develop treatments that protect liver function at an early stage of liver disease.

What inspired you to investigate the link between NETosis and liver fibrosis?

Liver fibrosis is a major health concern. If left untreated, it can eventually progress to liver cancer which ranks the third amongst cancer-related deaths globally. Thus, understanding the process that leads to liver fibrosis is essential for preventing progression to the irreversible stage. When I started my PhD candidature, I aimed to look into liver fibrosis from the angle of immune activation, in particular neutrophils and NETosis, which were understudied in this regard. Our inspiration came from earlier work showing that NETs promote organ scarring in aged mice and in tissue injury models. While in liver fibrosis, no study so far has identified the trigger of NETosis in the inflamed liver.

What was it like presenting your research at an international congress such as EASL in Amsterdam?

Presenting at international conference was both exciting and insightful. One of the most rewarding parts was meeting with experts that were interested in our studies. Their support reinforced the value of the findings and motivated me to keep pushing forward. Questions from them highlighted aspects that I can further explore, inspiring me to consider new angles. Besides, connecting with other researchers who faced similar hurdles was helpful. We shared experiences and solutions, which facilitated the progress of my research. Additionally, I also learned to tailor my explanations for different audiences. Clinicians focused more on practical outcomes, and basic scientists would like to know more of the mechanistic details. Adapting my message for each group improved my communication skills and deepened my understanding of our findings.

Did you receive any memorable feedback or questions during your poster session that stood out to you?

In the EASL Congress, while the majority of attendees were hepatologists, I was surprised that many of them were interested in the neutrophil-related immunobiology aspect of our work, and they were also working on neutrophil activation and NETosis in other contexts. Several researchers approached me on how NETs can be detected in organs, given the challenge of high autofluorescent background of the liver tissue. Through the discussions, we also shared alternative methods for the detection of NETs and discussed the pros and cons of these methods, including more sensitive biochemical assays for NET markers. I still maintain scientific exchange with the investigators along this line after the conference ended. I am delighted that our expertise in NETosis investigation has resolved methodological challenges that are encountered by scientists worldwide.

What are the next steps for your research following this recognition?

Building on the current findings, we will delve deeper into the cellular mechanisms. First, we aim to identify the specific cell types targeted by the newly repurposed treatment that we tested. This includes examining if the medication works by improving metabolism systemically, or targeting liver cells and/or immune cells directly. Second, we plan to characterise neutrophil heterogeneity in the fibrotic liver microenvironment and assess how the repurposed treatment alters neutrophil subsets. Third, given that patients with liver fibrosis also have extrahepatic comorbidities, we will also examine if there are other pleiotropic benefits of the treatment to other organs.

What challenges do you anticipate in translating your discoveries from the lab to clinical practice?

Basic science in the lab allows dissection of disease mechanism and hence discovery of new intervention targets. While the repurposed treatment is promising in treating liver fibrosis in mice, there is still some work before the findings can go into clinical practice. We will need to test in other mouse models of liver disease, such as drug-induced or virus-induced liver fibrosis, to examine whether the involvement of NETosis in scar formation (and hence the treatment) can be generalised to a wider spectrum of chronic liver disease. Besides, although drug repurposing significantly shortens the timeline for clinical application compared to novel drug development, Phase II clinical trial is still essential. Initial evaluation in carefully selected patient cohorts is required to establish proof-of-concept before expansion to larger populations.

How do you balance the demands of high-level research with your personal and academic commitments?

One of the most valuable lessons I learned during my PhD journey is the art of multitasking, especially when it comes to experiments. Since it takes long duration for disease conditions to develop in mice, I run multiple studies simultaneously to make the best use of my time. Second, maintaining a positive mindset is also necessary. When an experiment does not work (which happens often), I have learned not to get stuck; instead, the unexpected result may be pointing me toward a different question worth exploring, as my supervisor says. The biological world follows its own fascinating rules, and we need to patiently uncover them, even if it means taking a detour from our original plan. Besides, having meaningful hobbies outside the lab helps sustain stamina and clear the mind. My hobbies are my reset button, refreshing my energy which actually makes me better at science when I return to the lab.

Who or what has been your biggest source of support during your PhD journey?

My biggest source of support during my PhD journey is my supervisor, Nanyang Assistant Professor Christine Wong. While pursuing a PhD is never without its challenges, she supports me every step of the way. She remains deeply engaged in my progress, offering patient guidance on experimental design and troubleshooting. She always encourages us to think critically and explore alternatives. Her door is always open to us and she is always readily accessible, even on weekends or when she is overseas. Despite her busy schedule, she always makes time for our weekly meetings, which keep me focused and moving forward. Her mentorship helps me navigate technical hurdles and also shape the way I approach science.

You mentioned that your hobbies are your reset button, refreshing your energy. Share with us more on that.

I enjoy rock climbing, which I am grateful to discover through a friend who introduced me to this challenging yet rewarding activity. What I love the most about rock climbing is how it mirrors the problem-solving nature of research. Each climbing route presents a unique puzzle that needs to be solved step by step and I feel fulfilled about figuring out different approaches and techniques to reach the top. It has become more than just exercise; climbing builds the same kind of persistence and creative thinking that fuels my research. I am also interested in listening to investigative podcasts. They are like mental workouts. Following clues and piecing evidence together trains me to think analytically in ways that directly translate back to the lab. It is also a good way to stay curious while giving my brain a break from science.

Any other interesting experiences or thoughts/opinions you would like to share?

Curiosity and patience are precious in both research and life. In research, this means asking bold questions even if they challenge conventional dogmas, because breakthroughs often lie beyond textbook answers; in fact, textbooks do not have the answers. Maintaining the same curiosity and passion in everyday life is also essential. Research can be unpredictable. When those setbacks happen, we should keep in mind not to let them drain joy from other pursuits. Research is more than a career but also a mindset. Staying engaged with the world outside science, whether through hobbies, art, or simple observation, keeps the mind sharp and resilient and turns obstacles into stepping stones.