Staff Profile: Nanyang Assistant Professor Aditya Nair’s Endeavour in Uncovering the Neural Basis of Emotion States Using AI

| By Sanjay Devaraja |

Assistant Professor Aditya Nair was once encouraged to choose a conventional path, to satiate his curious mind, like medicine or engineering. But he chose science less a career choice and more like a calling – a way to ask the biggest questions while still keeping a clear line of sight to human health. That early tension, between wonder and practicality, still shapes his approach today: pursue fundamental mechanisms, but in a way that can ultimately make care more precise and humane.

That perspective took root during his undergraduate training at the National University of Singapore, where he studied life sciences while steadily expanding his computational toolkit. A research experience at Karolinska Institute, followed by a PhD in Computation & Neural Systems at the California Institute of Technology with Prof David J. Anderson, a renowned neuroscientist, clarified the kind of scientist he wanted to be – someone who uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) not as an end, but as a tool to discover neural mechanisms. He later continued this trajectory at Stanford University, carrying forward an approach that integrates AI with experimental neuroscience.

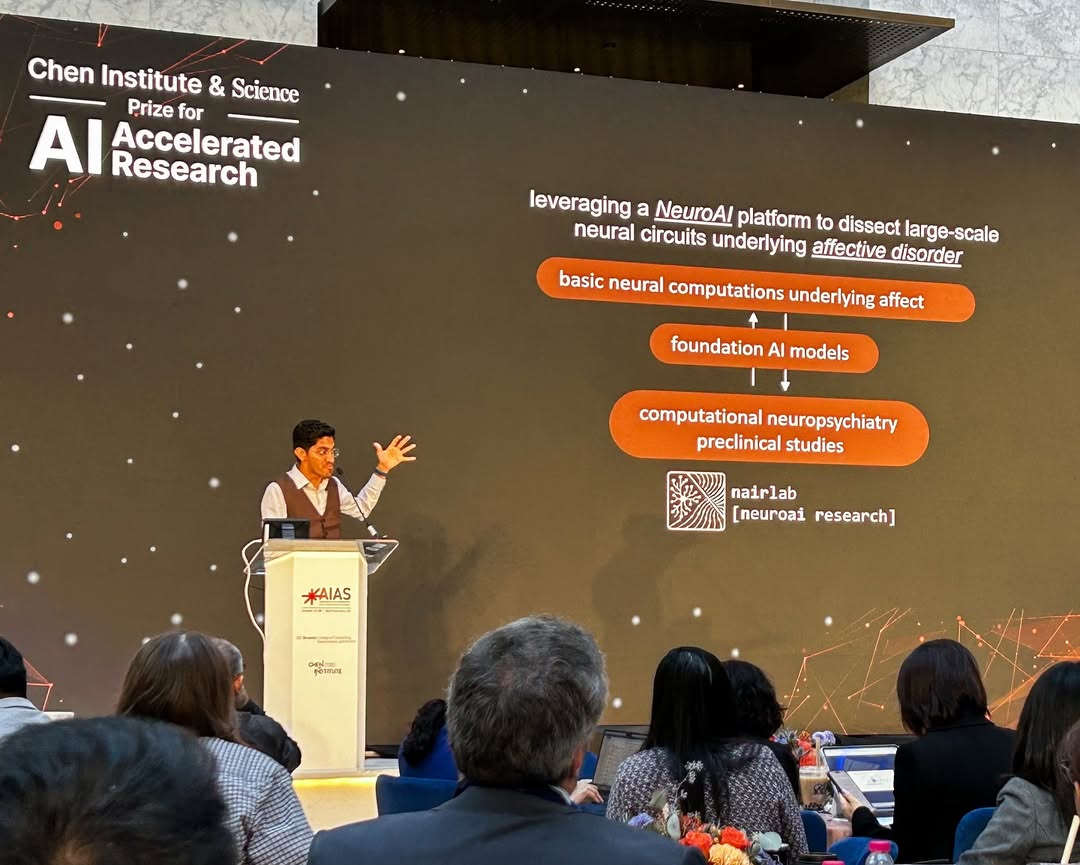

Today, Asst Prof Nair is a Nanyang Assistant Professor of Neuroscience and AI at LKCMedicine and a Principal Investigator at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research’s (A*STAR) Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology (IMCB). His work has been recognised across multiple communities, including being named a finalist for the Chen Institute & Science Prize for AI Accelerated Research, and receiving honours such as Caltech’s Ferguson Prize for Best PhD Thesis and the Society for Neuroscience’s Gruber International Research Award. These awards reflect a broader shift in the field – a growing belief that the next leaps in mental health will come from combining mechanistic neuroscience with rigorous, interpretable AI.

Finding the “State” Beneath the Noise

Asst Prof Nair says that emotion states can escalate, persist, and colour our perception long after the original trigger disappears. Yet the signals that underlie those states are notoriously difficult to pin down. Today’s technologies can record from hundreds to thousands of neurons at once – an extraordinary window into the brain – but the resulting data can be so complex that it obscures the governing principles we need to see.

His research starts with a simple idea: beneath the apparent complexity, the brain may be governed by a small set of underlying “variables” that evolve according to learnable rules. In this view, emotion is not best described as a list of categories; it is more like a trajectory, something brain activity enters, moves within, and eventually exits. The challenge is to identify those state variables and the rules that govern them.

To do that, he uses interpretable machine learning and computational models that search for latent structure in large-scale neural recordings. The goal is not to replace the brain with a model as complicated as the brain itself, but to find models that are understandable and testable, models that generate sharp predictions about what neural circuits are doing, moment by moment.

Attractors, Persistence, and Why Emotions Can “Stick”

A recurring theme in Asst Prof Nair’s work is that emotional states may be organised by stable dynamics in populations of neurons. One powerful concept from physics and engineering is the “attractor”, a pattern that complex systems like the brain naturally settle into and maintains. For emotion, this is especially compelling because it offers a mechanistic explanation for persistence, how an emotion state can remain stable even as noisy neural activity continues underneath.

In hypothalamic circuits, regions deeply involved in motivated behaviour and emotion, Asst Prof Nair and collaborators have found evidence for attractors that can explain the escalation and persistence of emotion-related states. A helpful metaphor is that activity in the brain moves like a volume knob, not a binary switch. Instead of the brain switching cleanly between two categories, certain neural circuit dynamics can support a continuous, graded representation of intensity. That kind of mechanism maps naturally onto experience – emotion states that ramp up, sustain, and only gradually return to baseline.

Importantly, these aren’t just descriptive patterns. They are hypotheses about how the brain stabilises emotion over time, hypotheses that can be tested causally. This model-to-mechanism philosophy is central to why his work has resonated beyond a single subfield.

For Asst Prof Nair, AI models are not the endpoint. They are hypothesis engines. His lab’s workflow is intentionally circular: AI-driven discovery leads to a clear prediction, which motivates a targeted experiment, which refines the biological mechanism. Bridging AI and biology is difficult: biological systems are noisy and context-dependent, while AI systems can be powerful but opaque. Asst Prof Nair’s strategy is to prioritise interpretability and falsifiability – build AI models that can be “read,” then pressure-test them with experiments designed to prove them wrong. If they survive, they earn the right to be treated as explanations, not just predictors.

Why it Matters for Mental Health – Toward Digital Twins

When emotional states linger too long, the consequences can be life-altering. Yet much of psychiatry still relies on symptom descriptions that are essential, but hard to quantify longitudinally and hard to map to neural mechanism. Asst Prof Nair’s work aims to add a complementary layer – measurable neural dynamics.

“If emotions can be treated the same way that cardiology treats heart rhythms, in terms of stable neural patterns, trajectories, recovery rates, then we can quantify not only what someone feels, but how their brain transitions between states, how easily it escalates and how long it persists. These properties align naturally with clinical concepts like resilience and vulnerability but translate them into trackable signals,” he says Asst Prof Nair.

This motivates a longer-term vision: digital AI twins for psychiatry. In Asst Prof Nair’s framing, a digital twin is not a sci-fi replica. It is an AI model that captures an individual’s brain-state dynamics well enough to simulate “what happens next” when the model is provided simulated drugs or therapeutic approaches. The promise is to move beyond trial-and-error care toward AI simulation-guided therapy. It is an ambitious goal, but it follows a pragmatic logic: if mental health is shaped by dynamical brain processes, then the most effective therapies may be those that can precisely target, and predictably reshape, those brain dynamics.

Priorities Shaped by Singapore’s Needs

At LKCMedicine, Asst Prof Nair is building a programme at the intersection between neuroscience, AI, and mental health, because that node is where Singapore has both urgent needs and unique strengths. Mental health challenges are increasingly visible across the lifespan, from over a third of young individuals in Singapore facing significant stress and anxiety according to the Institute of Mental Health.

His near-term focus is to develop robust, interpretable AI models that extract signatures of emotion and translate them from neural circuit-level principles to human-compatible signals. In parallel, he aims to lay practical foundations for digital twin approaches by building large scale AI models through collaborations that keep AI tethered to biology and clinical reality. What excites him most about LKCMedicine is the chance to do this work in an environment where medicine, computation, and rigorous basic science can genuinely co-design questions from the very start.

Asst Prof Nair often emphasises that scientific careers are not sustained by brilliance, but by a particular kind of endurance, a willingness to keep going when experiments fail, models break, or the truth refuses to be simple.

“Science is one of these places where it’s not really about being good or smart, but rather about being relentlessly hungry about wanting to know. That intrinsic drive will keep you going when your experiments fail or when things look challenging, because you always know that something beautiful and fascinating might just be around the corner.”