Research Story 1: LKCMedicine Student Plays Key Role in Uncovering Likely Early-warning Sign of Alzheimer’s Disease

| By Retna Devi D/O Shanmuga Retnam |

Being a medical student at LKCMedicine is not solely about developing an in-depth understanding of the anatomy and being exposed to patient care during clinical postings. It also entails going beyond clinical care and broadening their horizons by pursuing research through different opportunities, such as the Scholarly Project, a six-week research module in the fourth year of School.

For Justin Ong, a Year Five student, his journey to becoming a doctor included collaborating with LKCMedicine’s Dementia Research Centre (Singapore) (DRCS) to uncover a breakthrough in detecting Alzheimer's disease as part of his Scholarly Project and getting published in Neurology, the most widely read and highly cited peer-reviewed neurology journal.

The 23-year-old’s interest in the brain led to the discovery that “drains” in the brain responsible for clearing toxic wastes in the organ tend to get clogged up in people who show signs of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

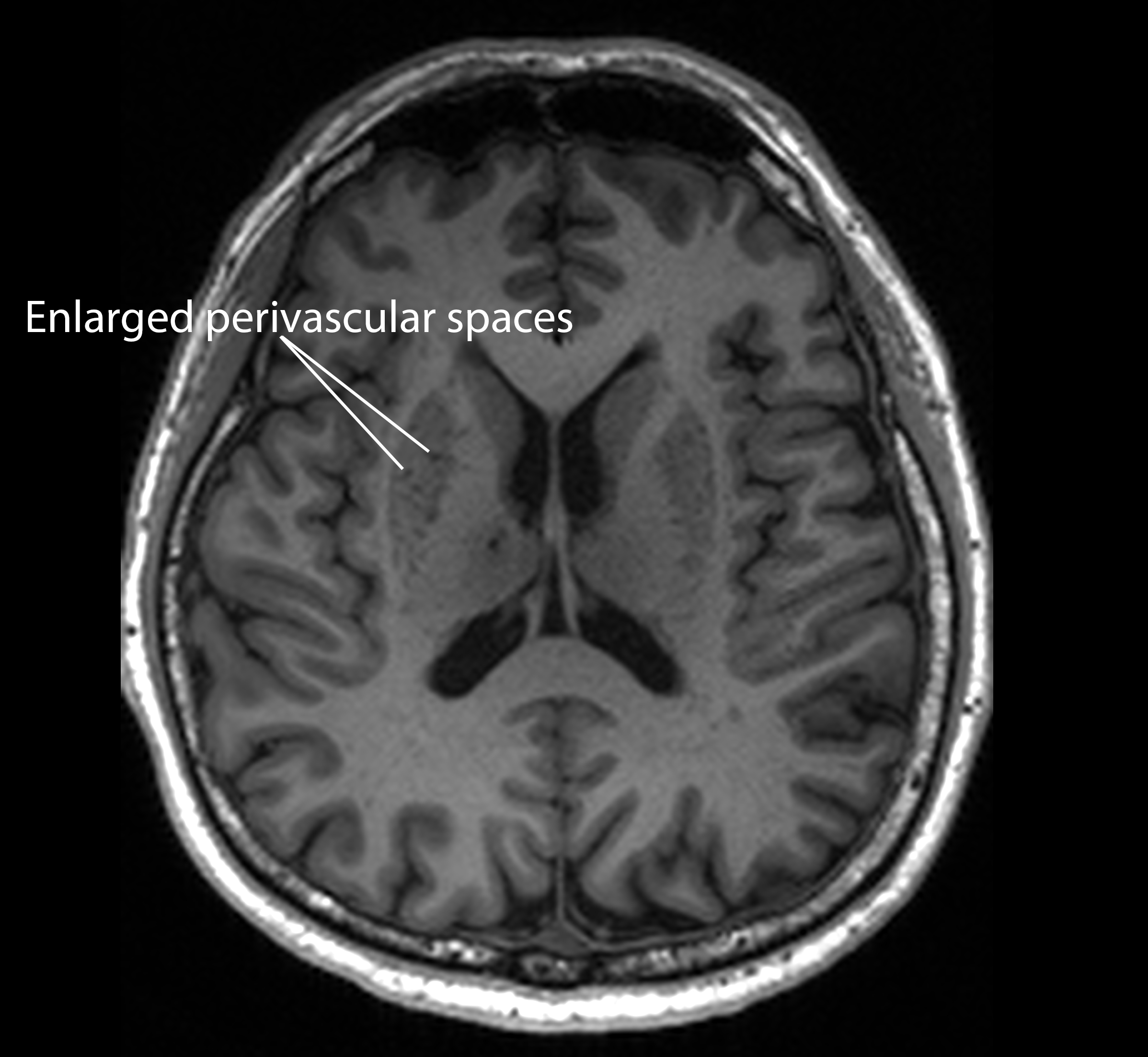

This suggests that such clogged drains, a condition known as “enlarged perivascular spaces”, are a likely early-warning sign for Alzheimer’s, a common form of dementia.

“Since these brain anomalies can be visually identified on routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed to evaluate cognitive decline, identifying them could complement existing methods to detect Alzheimer’s earlier, without having to do and pay for additional tests,” said DRCS Director Associate Professor Nagaendran Kandiah, the study’s senior author.

Justin, who primarily shaped the objective of the study, analysed the dataset and wrote the research paper as first author, added, “Detecting Alzheimer’s early is important because it allows clinicians to step in sooner to try and slow down the worsening of a patient’s cognitive issues like memory loss, slower thinking abilities and mood changes.”

The study, which took place over the course of a year, required him to gather data from close to 1,000 participants in Singapore, including nearly 350 who do not have any cognitive problems, meaning their mental abilities, such as their ability to think, remember, reason, make decisions and focus, are normal.

The data was drawn from DRCS’ on-going Biomarkers and Cognition Study that collects neuroimaging, blood biomarkers, and neuropsychological data from participants.

To make the link between enlarged perivascular spaces and dementia, specifically Alzheimer’s disease, Justin, together with researchers from DRCS, compared the blocked drains against beta amyloid proteins and damage to the brain’s white matter, which are hallmark indicators of Alzheimer’s disease; took seven measurements based on specific biochemicals in the participants’ blood, including beta amyloid and tau proteins that are known warning signs of the disease; and analysed MRI scans of the participants.

They found that those with mild cognitive impairment tend to have clogged drains in their brains, or enlarged perivascular spaces, compared to the other participants.

Additionally, the presence of clogged drains in the brain was linked to four of the seven biochemical measurements. So, people with enlarged perivascular spaces are likely to have more amyloid plaques, tau tangles and brain cell damage in their brains than normal, and thus at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Taking the study further, Justin compared white matter damage against enlarged perivascular spaces, and discovered that in participants with mild cognitive impairment, the link with biochemicals tied to Alzheimer’s was stronger for enlarged perivascular spaces than white matter damage. This suggests that choked brain drains are early indicators of Alzheimer’s disease.

Knowing all this allows clinicians to better figure out what kind of treatment they should use to slow and prevent Alzheimer’s disease early, possibly before permanent brain damage has happened.

Conducting an in-depth study with substantial clinical implications and juggling his studies was certainly no easy feat for Justin. “Working on a long project like this builds resilience. There were plenty of frustrating and tedious days where I felt like I was hitting a wall, but pushing through them was rewarding,” he reflected.

“Research has taught me to slow down and think more carefully about what I am seeing. It has also made me more aware of how much uncertainty there still is in conditions like Alzheimer’s. That awareness, I feel, will make me a more thoughtful doctor, someone who can explain diagnoses and limitations honestly to patients and their families. Being aware of this will also make me a more curious doctor, who will want to look a little deeper in day-to-day clinical practice.”