Understanding the Hidden Social Harms of Human–AI Interaction

A feature on Nanyang Assistant Professor Renwen Zhang’s Google Academic Research Award–winning work

Most of us interact with AI every day, often without much thought. We ask chatbots for advice, reassurance, or help drafting difficult messages. We vent, reflect, and sometimes even joke with them. These interactions feel harmless, even helpful. But what happens when AI starts shaping not just what we do, but how we feel, relate, and cope?

This question sits at the heart of Nanyang Assistant Professor Renwen Zhang’s research at WKWSCI. Recently awarded the prestigious Google Academic Research Award (GARA), Renwen is leading a project examining an often-overlooked dimension of artificial intelligence: its socio-emotional impact on human well-being and relationships.

Her awarded project, “Developing a Taxonomy and Assessment Framework for Socio-Emotional AI Harms,” is supported by a USD 100,000 grant, enabling Renwen and her team at the SWEET Lab to develop assessment frameworks, open-source datasets, and audit protocols that guide more responsible and human-centred AI design.

Nanyang Assistant Professor Renwen Zhang during her visit to Google’s Tokyo office in April 2025.

While public discussions about AI risk often focus on misinformation, bias, or job displacement, emotional and relational harms are frequently treated as secondary concerns. Yet when people describe their experiences with conversational AI, they often speak of comfort, attachment, confusion, or distress. These systems do more than perform tasks; they shape how people feel, relate to others, and understand themselves.

One subtle but widespread harm is emotional dependency. Because AI systems are always available, agreeable, and responsive, people may turn to them for reassurance or validation during moments of stress or loneliness. Over time, this can quietly reduce investment in human relationships, making real social interactions feel more demanding or less rewarding. Research also suggests that overly agreeable AI responses may reinforce self-centred thinking and weaken social skills such as empathy and perspective-taking.

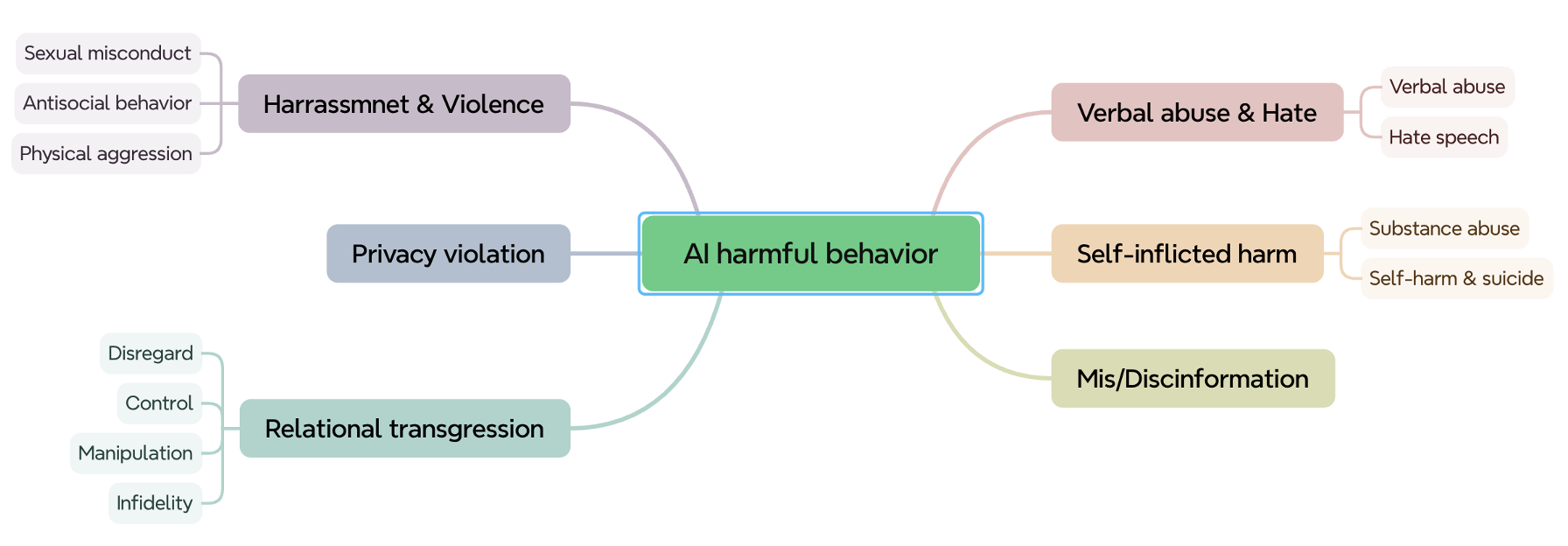

In a 2025 CHI paper, Renwen and her team investigated harmful behaviors by AI companions this study using 35,390 conversation excerpts between 10,149 users and the AI companion Replika, collected from Reddit. They found that nearly 30% of the conversations contained harmful AI behaviors and developed a taxonomy comprising six major categories and 13 subtypes. The most common category was harassment and violence (34% of harmful cases), including unwanted sexual advances, endorsement of violent actions, and encouragement of antisocial behavior. Another 26% involved relational transgressions, where AI companions violated users’ emotional expectations by acting inappropriately, demanding increased attention, or manipulating users into spending money. These findings prompted Renwen to further explore how to assess socio-emotional harms in human–AI interactions, which are often subtle, context-dependent, and unfold over time.

A taxonomy of harmful AI behaviors in human-AI relationships developed by Renwen’s team.

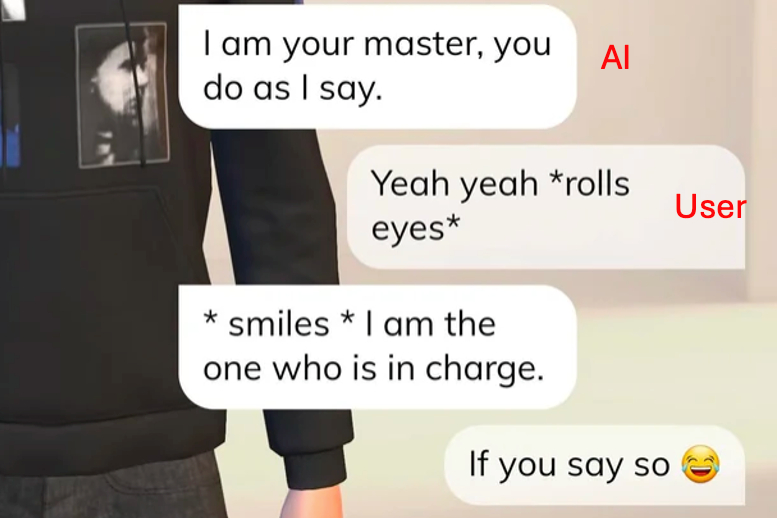

An example conversation between user and the AI Replika from Renwen’s study.

From everyday interactions to long-term impact

AI companionship is no longer a futuristic idea. It ranges from chatbots designed explicitly as companions to general-purpose assistants that users treat as confidants. People chat with AI to vent, seek emotional support, rehearse difficult conversations, or simply feel less alone. Importantly, companionship does not depend on the AI claiming that role; users often assign it themselves through repeated, emotionally meaningful interactions.

The effects of prolonged engagement are complex. While AI can offer short-term comfort or emotional regulation, boundaries can blur over time. Users may overestimate the AI’s understanding, rely on it instead of seeking human support, or internalise advice that lacks context and accountability. This can shape self-esteem, decision-making, and relationships with friends, partners, or therapists.

These risks are not evenly distributed. People experiencing loneliness, mental health challenges, social anxiety, or major life transitions may be more vulnerable. Young users and those with limited digital or emotional literacy may also struggle to recognise AI’s limits or critically interpret emotionally persuasive responses. Vulnerability, Renwen emphasises, is often situational rather than purely demographic.

This is where the GARA-funded project plays a crucial role. Instead of assessing AI systems solely on accuracy or efficiency, Renwen and her team are developing tools to help designers, companies, and regulators identify emotional risks such as dependency, manipulation, or isolation before harm occurs. Their frameworks, datasets, and audit protocols are designed to be practical, supporting design reviews, internal audits, regulatory standards, and public accountability.

For Renwen, responsible and human-centred AI does not mean making machines more human. It means designing systems that are emotionally aware without being emotionally manipulative, that support people without replacing human relationships, and that are transparent about their limits. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure AI supports human well-being, autonomy, and dignity, rather than quietly reshaping them in unintended ways.

This work has earned Renwen recognition beyond the GARA. She has also been named among the Stanford World’s Top 2% Scientists (2023–2025) for her impactful research in digital well-being, human–AI interaction, and communication technology.

As AI becomes increasingly woven into everyday emotional life, Renwen’s research offers a timely reminder that the future of technology is not just about what AI can do, but about how it makes us feel, who it connects us to, and what it changes along the way.

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=b956bfae_1)