The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics: Bringing Quantum Mechanics into the Macro World

Prof Christos Panagopoulos | School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (SPMS), NTU

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics honours John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for a discovery that seems almost paradoxical: they showed that quantum mechanics, usually confined to atoms and subatomic particles, can govern the behaviour of an entire electric circuit, large enough to hold in your hand.

In the 1980s, these pioneers worked with superconducting circuits built around Josephson junctions—tiny structures where two superconductors are separated by an ultrathin insulating barrier. Within these circuits, electrons pair up into so-called Cooper pairs, moving collectively and coherently. This synchronisation allows the entire device to behave as a single quantum object, bridging the microscopic and macroscopic worlds.

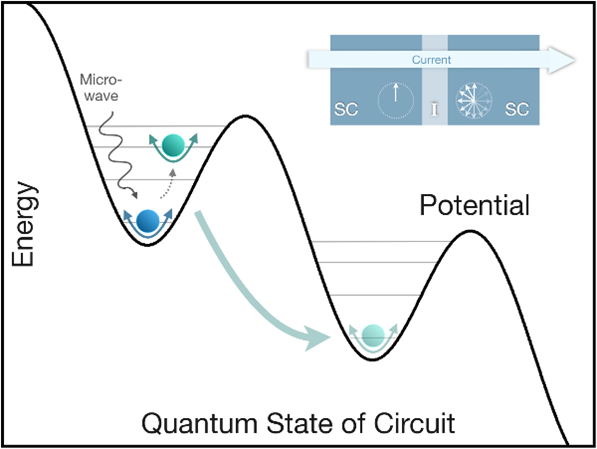

The physics behind this behaviour is beautifully captured by the tilted washboard potential. In a current-biased Josephson junction, the quantum state of the circuit behaves much like a ball trapped in one of the ripples of a slanted washboard. The slope of the board corresponds to the applied current; the ripples represent the potential wells created by Josephson energy. When Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis probed these systems, they found two astonishing phenomena that map directly onto the features illustrated in the schematic.

The potential energy landscape of a current-biased Josephson junction (top right) forms a tilted washboard, where the superconductor/insulator/superconductor (SC/I/SC) circuit’s quantum state behaves like a ball in a potential well. The phase difference between the two superconducting electrodes (shown as a clock-like phasor) changes by 2π with each tunnelling event. Two macroscopic quantum effects appear: direct quantum tunnelling between wells (green arrow) and microwave-assisted tunnelling via discrete excited states (grey arrows), revealing quantised energy levels.

The potential energy landscape of a current-biased Josephson junction (top right) forms a tilted washboard, where the superconductor/insulator/superconductor (SC/I/SC) circuit’s quantum state behaves like a ball in a potential well. The phase difference between the two superconducting electrodes (shown as a clock-like phasor) changes by 2π with each tunnelling event. Two macroscopic quantum effects appear: direct quantum tunnelling between wells (green arrow) and microwave-assisted tunnelling via discrete excited states (grey arrows), revealing quantised energy levels.

Image Credit: Adarsh Hullahalli and Xinyang Zhang from SPMS, NTU.

First, the circuits exhibited macroscopic quantum tunnelling. In the washboard picture, this is the ball slipping through the wall of a ripple rather than rolling over it. Even though billions of electrons participate, the entire circuit tunnels as a single quantum object. Notably, this behaviour was previously associated only with microscopic particles. Second, they observed energy quantisation within each well of the washboard. The stacked horizontal lines in the figure represent discrete quantum energy levels. When microwaves were applied, the circuit absorbed energy only in fixed, quantised steps, causing the “ball” to jump between these levels. This is exactly the kind of transition normally seen in atoms, yet here it occurred in a macroscopic electrical device.

By grounding their experiments in the physics represented in the washboard potential, Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis demonstrated something profound: quantum mechanics does not fade away once you scale up to everyday objects. Instead, under the right conditions, such as superconductivity, it can dominate even at human-made, macroscopic scales. Beyond its intellectual elegance, this work reshaped fundamental physics. It challenged the long-standing question: Where does the quantum world end and the classical world begin? The answer is that the boundary is far more flexible than previously thought.

These insights also laid the foundation for modern technologies. Superconducting qubits, which are the heart of many quantum computers, directly exploit the discrete energy levels and tunnelling processes depicted in the washboard potential. Today’s ultrasensitive sensors, quantum processors, and precision measurement devices all trace their lineage back to these experiments.

John Clarke’s early work illustrates the power of curiosity-driven research. During his PhD, completed in 1968 at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, Clarke was challenged by his advisor, Brian Pippard: could the strange quantum effects predicted by Brian Josephson (Nobel Prize 1973), also in their group, be harnessed to create the world’s most sensitive voltmeter? Clarke accepted the challenge, giving birth to SQUIDs (Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices). The first prototype, the “SLUG” (Superconducting Low-inductance Undulating Galvanometer), looked like a blob of solder with two wires sticking out. Yet, it ignited a revolution in precision measurement.

-(10).jpg?sfvrsn=d42ce0dc_1) Image Credit: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/summary/

Image Credit: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/summary/

The 2025 Nobel Prize is a testament to patience, vision, collective thinking, and persistence in science. Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis began with fundamental questions, trusting that deep understanding would eventually open new doors. Their decades-long work now underpins some of today’s most exciting quantum technologies.

For the NTU community, this prize resonates deeply. Like last year’s recognition of breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, it highlights NTU’s growing strengths in quantum science and engineering. It serves as a reminder that bold, curiosity-driven research can reshape our understanding of nature (φύσις, phýsis) and that the fundamental laws of physics continue to inspire the technologies of tomorrow.

For more information about the prize, watch the short video here.

-(33).tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=34b677a6_1)