The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: Metal-Organic Frameworks Open New Rooms for Chemistry

Prof Zhao Yanli and Dr Liu Bai-Tong | School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology (CCEB), NTU

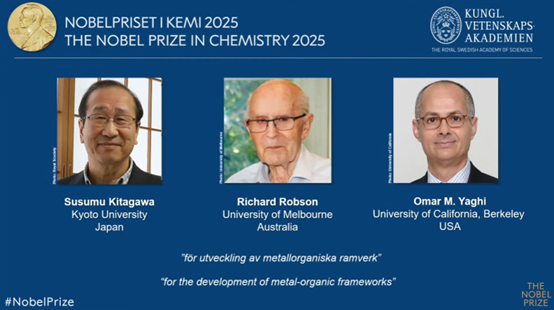

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to Prof Susumu Kitagawa (Kyoto University), Prof Richard Robson (University of Melbourne), and Prof Omar Yaghi (University of California, Berkeley) for the development of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)—a revolutionary class of materials that have transformed how chemists design and carry out practical functions.

Image credit: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/summary/

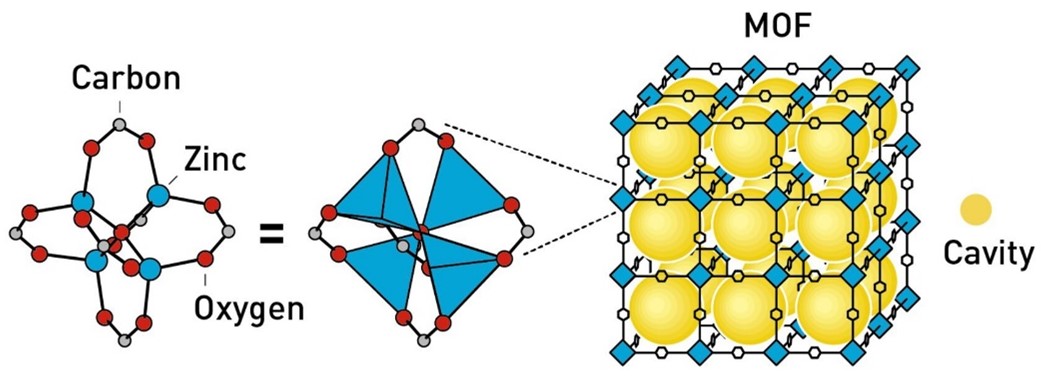

Image credit: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/summary/

MOFs are crystalline materials built from metal ions (or clusters) and organic linkers that assemble into highly ordered, porous architectures. Often described as “molecular buildings,” they contain vast internal cavities through which guest molecules can flow in and out. This unprecedented “inner space” endows MOFs with exceptional capacity for storage, separation, and catalysis.

Unlike conventional porous materials, MOFs are rationally designable. By choosing different metal nodes and organic linkers, chemists can tailor pore size, shape, flexibility, and chemical functionality with architectural precision. This modularity has enabled the creation of thousands of distinct MOFs, each optimised for a specific task. Today, MOFs are being explored to harvest water from desert air, capture carbon dioxide, remove perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances as well as other pollutants from water, store hydrogen safely, deliver pharmaceuticals for disease treatment, and confine or decompose highly toxic species.

The story begins in the late twentieth century, when Prof Richard Robson realised that metal ions and multitopic organic molecules could be combined to form extended crystalline networks, much like atoms in diamond. Against expectations, these components did not collapse into disordered “molecular bird’s nests,” but instead organised into regular structures containing large cavities. Robson’s early frameworks were fragile, yet they demonstrated a radical idea: molecular building blocks could be programmed to form spacious architectures.

In the 1990s, Prof Susumu Kitagawa took this concept further. Guided by his philosophy of seeking “the usefulness of the useless,” he showed that such frameworks could be made stable and functional. His group created three-dimensional MOFs with open channels that could adsorb and release gases without losing their structures. Even more remarkably, Kitagawa recognised that MOFs could be soft materials. Unlike zeolites, which are rigid, MOFs can be flexible—capable of “breathing,” changing shape as they take in or release guest molecules. This property opened entirely new directions for responsive and adaptive materials.

Prof Omar Yaghi provided the unifying vision and methodology that transformed these early discoveries into a global field. He coined the term metal–organic frameworks and established the principles of reticular chemistry: the rational assembly of materials from well-defined building units. In 1999, his group introduced MOF-5 (Figure 1), a landmark material whose internal surface area is so enormous that a few grams can contain the equivalent of a football pitch. Yaghi further demonstrated that entire families of MOFs could be systematically designed by varying molecular linkers, giving unprecedented control over pore size, shape, and function.

Figure 1. In 1999, Yaghi et al. constructed a material, MOF-5, which has cubic spaces. Just a couple of grams can hold an area as big as a football pitch. ©Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Because of the unique porosity and organic-inorganic nature of MOFs, they are suitable systems for drug delivery and biocatalysis in disease treatment. One of key research interests from our group at NTU focuses on the design and applications of MOF-based nanomedicine. At the nanoscale, MOFs combine high porosity, modular chemistry, and intrinsic degradability, enabling exceptional loading of drugs, proteins, and nucleic acids for stimulus-responsive release. Another fast-growing direction is MOF-enabled phototherapy. For example, porphyrin-based nanoscale MOFs have been developed as theranostic platforms that integrate drug delivery, bioimaging, and photodynamic or photothermal therapy within a single material. These properties allow MOFs not only to act as passive carriers, but also as active therapeutic agents whose metal nodes and organic linkers participate directly in disease treatment. Such capabilities position MOFs and their composite nanomaterials as a promising class of theranostic systems for precision medicine.

During awarding this prize, the Nobel Committee emphasised that MOFs have “created new rooms for chemistry.” Beyond their immediate applications, MOFs represent a new paradigm: chemistry is no longer limited to synthesising molecules but can now build spaces at the molecular scale. This architectural control opens transformative possibilities for addressing grand challenges in energy, environment, and health.

For more information, visit the Nobel Prize website and watch the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry overview video here.

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=c45c3c7e_1)