How To Build a Qubit? by Prof Valla Fatemi

IAS@NTU STEM Graduate Colloquium Jointly Organised with the Graduate Students' Clubs

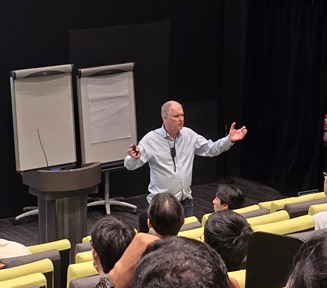

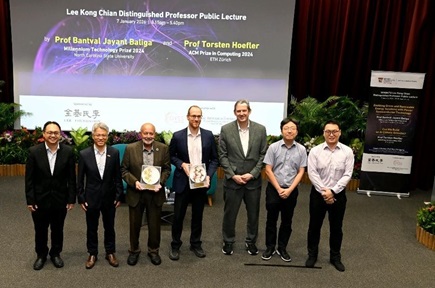

On 13 January 2026, the Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) at NTU, hosted a colloquium by Prof Valla Fatemi, in collaboration with the Graduate Students' Club of the School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (SPMS). The colloquium titled, "How to Build a Qubit?", addressed a deceptively simple question that lies at the heart of quantum technologies today: What does it actually mean to build a qubit, and why should we learn how to do it in the first place? To answer this, the talk began by stepping back to place quantum computing within the broader historical arc of technological revolutions driven by our understanding of quantum physics.

Prof Valla Fatemi explores what it truly means to build a qubit, situating quantum computing within the history of quantum-driven technological revolutions.

Prof Valla Fatemi explores what it truly means to build a qubit, situating quantum computing within the history of quantum-driven technological revolutions.

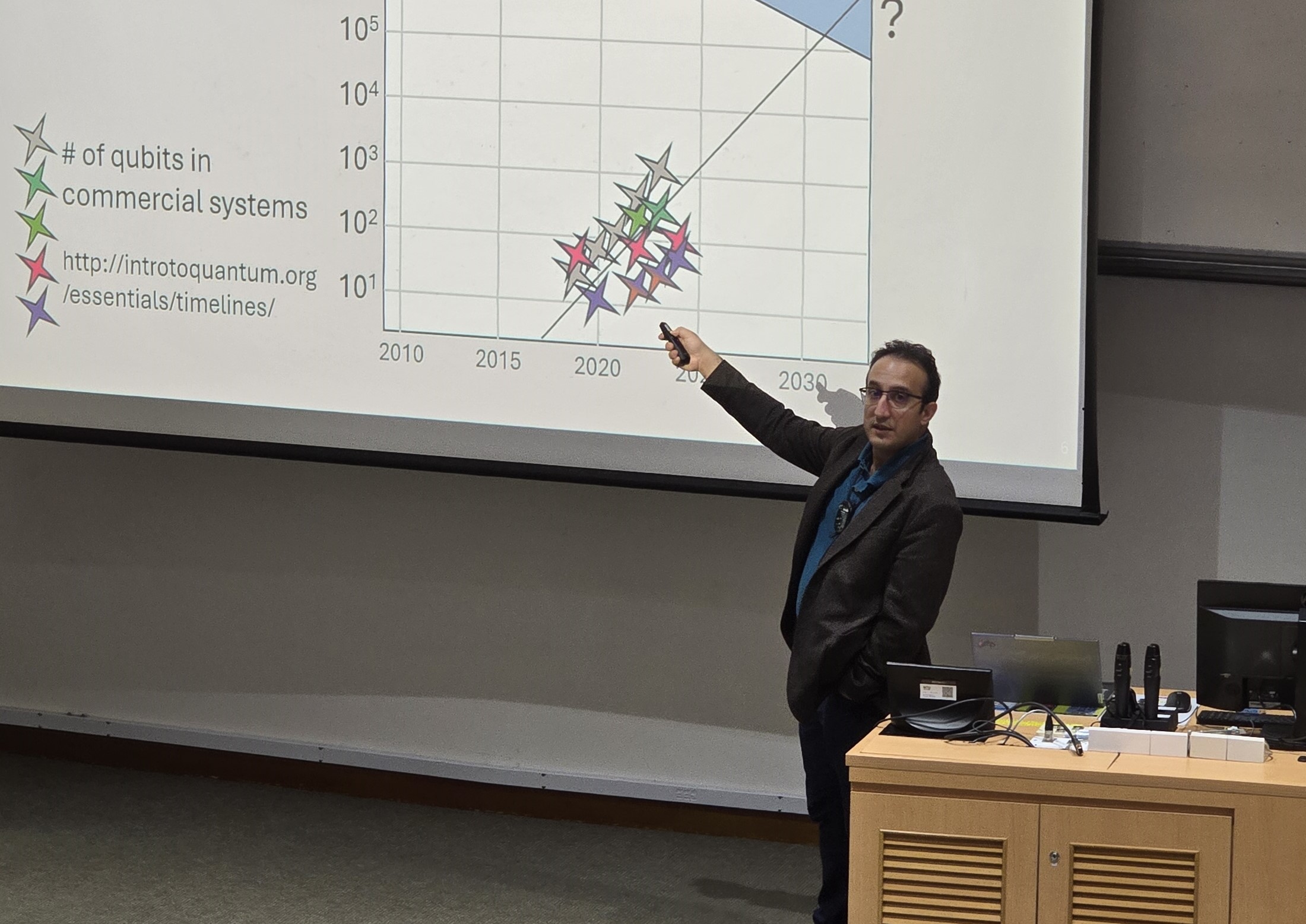

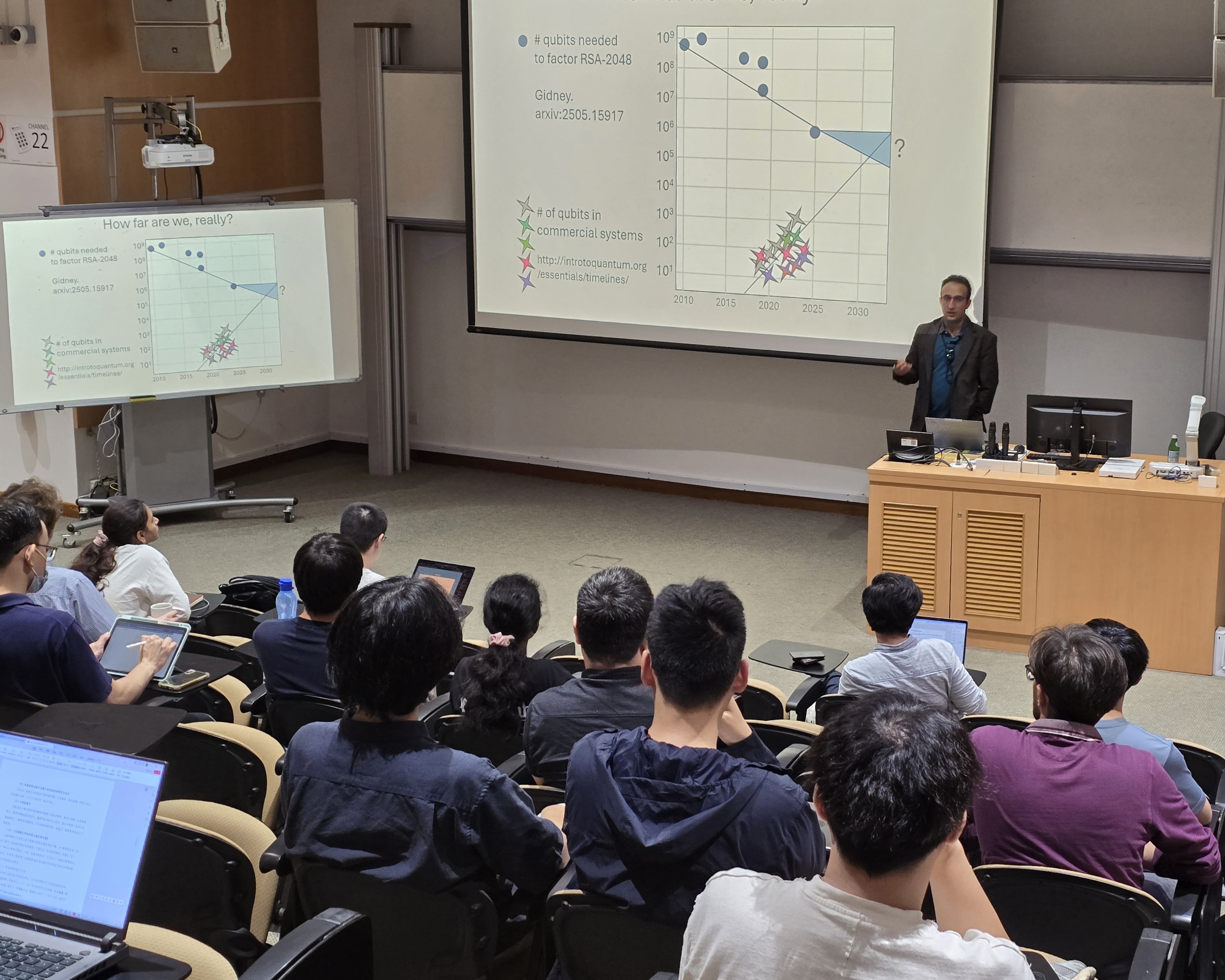

The first quantum revolution - driven by our understanding of how electrons behave in a lattice - gave rise to digital electronics, transistors, and modern computing that has seamlessly integrated into our everyday lives. That journey began with basic scientific insights from quantum mechanics, progressed through development of fundamental components, and eventually scaled into complex, useful technologies. Today, we find ourselves amid a second quantum revolution, which stemmed from our need to not only understand quantum behavior, but to control it and harness the quantum-ness - like superposition and entanglement - and build entirely new kinds of devices. The end goal is to build a quantum computer. But, how far along are we?

From a hardware perspective, state-of-the-art quantum processors currently operate on the order of hundreds of qubits. However, from an algorithmic complexity standpoint, the infamous Shor’s problem would require millions of qubits to be solved efficiently. Whether these two trajectories will converge in the coming decade remains uncertain, but it is precisely this gap that motivates a deeper examination of how qubits are built and what limits their performance.

Conceptually, a qubit is just a simple two-level system used to encode quantum information. Unfortunately, such a deceptively simple and elegant system is just too ideal to exist. A realistic two-level system interacts with the environment and with unwanted (energy) levels. These interactions lead to three major challenges: relaxation, dephasing and leakage. Instead of chasing a pipe dream, Prof Fatemi emphasised a more practical question: what characteristics make a qubit useful?

Prof Fatemi examines the gap between ideal qubits and reality, highlighting decoherence challenges shaping practical quantum computing.

Prof Fatemi examines the gap between ideal qubits and reality, highlighting decoherence challenges shaping practical quantum computing.

Answer to this question is succinctly captured by DiVincenzo’s criteria for building a quantum computer, which outlines five essential requirements for a functional and scalable quantum computer. These include the ability to initialise qubits in a well-defined state, implement a universal and fast set of quantum gates, perform qubit-specific measurements, maintain quantum coherence over sufficiently long timescales, and scale the system within a well-characterised physical platform. These criteria serve as a practical benchmark against which different qubit technologies can be assessed.

Qubit technologies today broadly fall into two categories: natural atomic qubits and artificial atomic qubits. Natural atom qubits, like trapped ionic qubits and Rydberg atom qubits, rely on well-defined energy levels that occur naturally in atomic spectra. In trapped ion platforms, individual ions are confined using a combination of static and oscillating electric fields and cooled with lasers, with quantum information stored in either hyperfine states or long-lived electronic states. These systems offer exceptional coherence and precise control, but face challenges when it comes to large-scale integration. Rydberg atom qubits, created through strong interactions between highly excited atoms via the Rydberg blockade mechanism, enable fast gate operations and flexible geometries, yet come with their own trade-offs in stability and control.

Exploring natural atomic qubits, from trapped ions to Rydberg atoms, balancing coherence, control, scalability, and fast quantum operations.

Exploring natural atomic qubits, from trapped ions to Rydberg atoms, balancing coherence, control, scalability, and fast quantum operations.

Artificial atomic qubits take a different approach. Rather than relying on naturally occurring atomic spectra, these systems are discrete, quantised energy levels in man-made engineered systems, typically using electronic circuits. Among these, superconducting qubits have emerged as one of the most widely explored and technologically mature platforms. The basic building block is an LC circuit, whose quantised energy levels resemble those of a harmonic oscillator. On its own, however, such a system does not form a qubit, as its energy levels are evenly spaced. The crucial step is the introduction of anharmonicity by replacing the inductor with a Josephson junction, a nonlinear circuit element that fundamentally alters the energy spectrum and enables the isolation of two usable quantum states. By tuning the relative strengths of the Josephson energy and the charging energy, different types of superconducting qubits emerge, including charge qubits, flux qubits, and phase qubits. These engineered systems exemplify the idea of artificial atoms: quantum devices whose properties can be designed and optimised.

Since the first breakthrough in 2001, when Nakamura et al. demonstrated coherent control of a superconducting charge qubit based on a Cooper-pair box, the field of superconducting qubits has advanced rapidly along multiple fronts. Progress has been driven not only by the development of circuit quantum electrodynamics - which enabled strong coupling between qubits and microwave photons - but also by sustained efforts to understand and mitigate loss mechanisms at the materials level, as well as to improve scalability and gate fidelities. The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis, stands as a recognition of how the macroscopic manifestation of quantum mechanical phenomena in electrical circuits has transformed both fundamental research and technology development, further cementing the prominence of superconducting qubits. Today, superconducting platforms remain at the forefront of quantum hardware, with processors comprising hundreds of qubits and gate fidelities approaching the thresholds required for fault-tolerant quantum computation.

Looking to the future, Prof Fatemi outlines key challenges and champions hybrid qubit systems shaping the next phase of the quantum revolution.

Looking to the future, Prof Fatemi outlines key challenges and champions hybrid qubit systems shaping the next phase of the quantum revolution.

Despite remarkable progress, coherence remains a key limiting factor. Looking ahead, Prof Fatemi highlighted several critical challenges that must be addressed to realise a fully functioning quantum ecosystem: achieving high-fidelity gates, improving device packaging, filtering out undesirable radiation, and perhaps most importantly - developing ways to connect and integrate different types of qubits. Rather than searching for a single “best” qubit technology, the future of quantum computing may lie in hybrid systems that combine the strengths of multiple platforms. By placing individual qubit platforms within the context of the second quantum revolution, the colloquium underscored both how far the field has come, and how much remains to be done.

---copy.jpg?sfvrsn=54c7f8c0_1)

This colloquium is held in conjunction with the ongoing IAS Frontiers Seminars: Quantum Horizons series. Find out more about the upcoming seminars and register here.

Written by: Adira Mohitha | NTU School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences Graduate Students' Club

“The discussion of the various types of Qubits and how one type can be more suited for certain purposes was really enjoyable.” – Mustafa Ameer (PhD student, EEE)

"I enjoyed when he explained about ion traps and the Josephson junction" - Rafika Rahmawati (PhD student, MSE)