"Do The Impossible": An Hour of Inspiration with Millennium Technology Prize Winner Prof Stuart Parkin

Written by Shrikant Ameya Sunil | PhD student, CCDS NTU

It was a rare afternoon where time seemed to bend—not because of theoretical physics, but because an entire room of young minds found themselves gripped by the stories, ideas, and provocations of one of the world’s foremost experimental physicists. Prof Stuart Parkin (Millennium Technology Prize 2014), a pioneer of Spintronics and current Director at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics, joined NTU students for an hour-long interactive tea session that proved to be anything but ordinary.

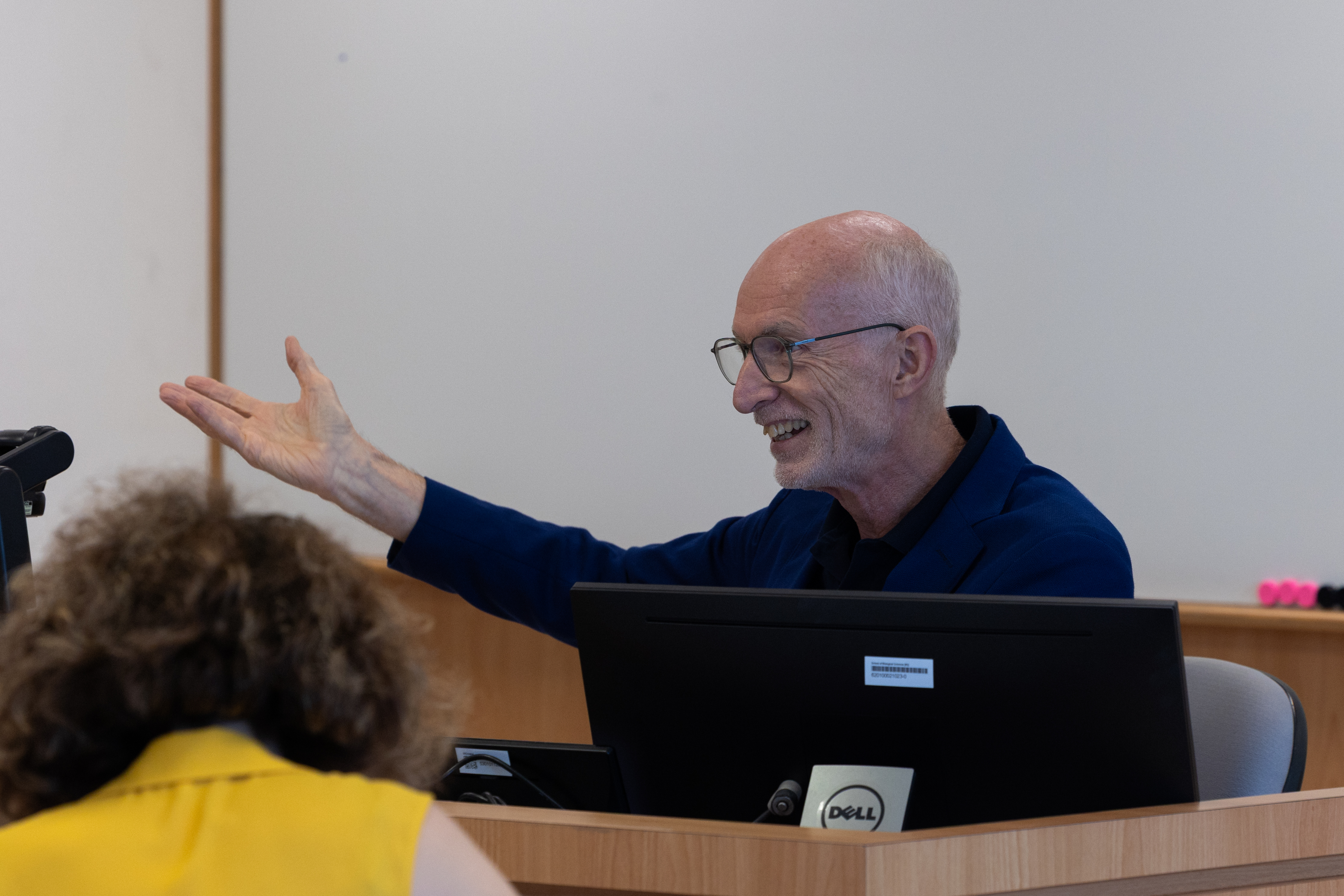

Prof Stuart Parkin captivates NTU students in an interactive tea session on spintronics and innovation.

Prof Stuart Parkin captivates NTU students in an interactive tea session on spintronics and innovation.

From candid recollections of failed experiments to multi-million-dollar lab builds, the conversation moved fluidly—driven as much by students’ eager questions as by Prof Parkin’s generous storytelling. It was not a lecture. It was a journey through decades of scientific curiosity, trial-and-error, and the art of thinking differently.

When a student asked what drew him into science, Prof Parkin traced his origins not to equations, but to cacti. “I was fascinated by how plants like cacti have structure across different scales,” he said. That interest evolved into studying crystalline solids during his undergraduate years at Trinity College, Cambridge—chosen, he added with a grin, “because that’s where Newton went.”

Initially drawn to chemistry, he quickly pivoted to physics. “Chemistry felt too messy. Physics had fewer equations, but it could explain the world.” Students chuckled, perhaps recognising their own battles with organic synthesis and reaction mechanisms.

Even during his undergraduate days, Parkin showed a flair for self-direction. Despite choosing a theoretical physics track, he opted to pursue a PhD in experimental physics. He dove into research on van der Waals materials; layered systems that would later underpin graphene studies, and built his own instruments to probe their magnetic and transport properties. “I basically built everything myself,” he recalled.

Prof Parkin shares how childhood fascination with cacti led him from chemistry to physics at Cambridge.

Prof Parkin shares how childhood fascination with cacti led him from chemistry to physics at Cambridge.

After his PhD, Parkin worked in Paris on organic molecular crystals believed to hold promise for superconductivity. But when he joined IBM in California, the entire project was cancelled within two years. “Thirty people had to find new directions,” he said. For Prof Parkin, that meant returning to magnetism and eventually laying the foundation for a transformative body of work.

Determined to explore magnetic multilayers, he convinced IBM to invest $1.2 million in a Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) system. But when a specialist joined the team, Prof Parkin was sidelined. He then cobbled together a sputtering system using $50,000 and surplus parts. “That little system could make 20 wafers a day, and it outperformed the fancy MBE,” he said. It became the engine behind his landmark discoveries in oscillatory interlayer coupling and spin-valve structures—pivotal developments that redefined data storage technologies.

When asked how he chooses what problems to tackle, Prof Parkin replied without hesitation: “If you already know how to do it, then I’m not interested. We should be doing the impossible.” Even as his responsibilities grew, his approach remained grounded in deep, hands-on experimentation. After being named an IBM Fellow, he gained executive-level autonomy and built a sprawling $10 million multi-chamber deposition system he dubbed MANGO, “because I like naming my systems after fruit,” he laughed.

Prof Stuart Parkin inspires students to pursue bold, original research beyond trends, shaping science’s future.

Prof Stuart Parkin inspires students to pursue bold, original research beyond trends, shaping science’s future.

While his curiosity is boundless, Parkin emphasised the importance of real-world applications. “You can’t just show one cool property and declare victory. A material must be manufacturable, stable, and scalable. That’s what I learned from industry,” he explained.

A highlight of the session came when he discussed racetrack memory, which is a novel, non-volatile data storage system. Prof Parkin’s team is now developing cryogenic variants compatible with quantum computing systems, where classical control memory is still a critical bottleneck. “If you could build memory directly on-chip at cryogenic temperatures, you’d solve massive latency and energy problems,” he explained.

Reflecting on the nature of scientific hype, Prof Parkin warned against blindly following trends. “Everyone did 2D materials for five years, then left. Same with high-Tc superconductors. If everyone is doing something, it’s probably not that original,” he advised. Instead, he urged students to explore directions no one else was pursuing, beyond the obvious, beyond the incremental.

Asked whether he ever felt lost working independently, Parkin smiled. “Not really. I’ve always loved science. There’s nothing better to do.”

As the discussion came to a close, one student asked a heartfelt final question: “Is there anything you want the world to know, about your working style, your thinking, or just a message to us, the next generation?”

Prof Parkin paused, then responded with quiet conviction: “I want the youth to know that research has a lot to offer. Don’t run away from it. Money plays a role on the personal front, of course. But eventually, that too gets taken care of.”

It was a message not just about science, but about belief — belief in curiosity, in the process, and in a future shaped by those bold enough to chase the unknown.

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=c45c3c7e_1)