NTU scientists tap metal-eating microbes to recycle lithium-ion batteries

First published on The Straits Times

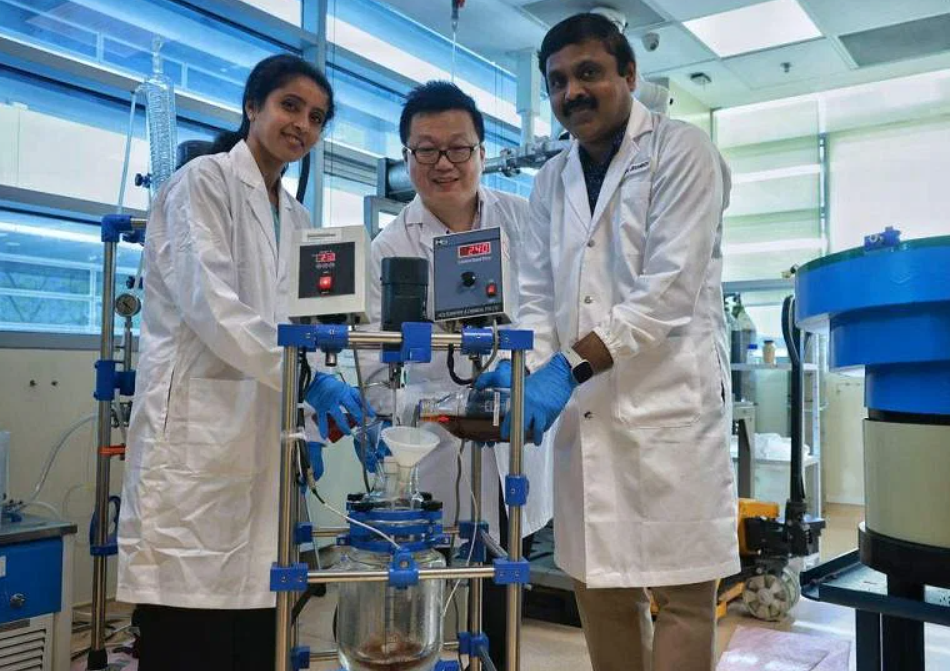

(From left) Professor Madhavi Srinivasan, team lead of the project; NTU Associate Professor Cao Bin, co-leader of the project; and Dr Joseph Jegan, senior researcher at ERI@N. ST PHOTO: JASON QUAH

SINGAPORE – Microbes that eat up valuable metals from spent lithium-ion batteries are moving out of the lab to recycling plants.

Scientists from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) are working with several companies to explore processing one to five tonnes of lithium-ion battery feedstock, said Professor Madhavi Srinivasan, team lead of the project.

Referred to as black mass, the powdered feedstock is mixed with a liquid microbial culture. The process, called bioleaching, produces metabolites that extract valuable materials like lithium, manganese, nickel, cobalt, iron and graphite.

Recovery rates of these metals can range from 85 per cent to 92 per cent in six hours, with up to 150g of the black mass being mixed into every litre of the culture.

It is one of the more efficient bioleaching processes developed so far, said Prof Madhavi, who is executive director of the Energy Research Institute @ NTU (ERI@N).

“The reason using microbes is not adopted in the industry is... the amount of black mass metabolised is too low,” she noted.

Said project co-leader and NTU Associate Professor Cao Bin, from the Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering: “The black mass is toxic to the microbes. And in other studies where researchers tried to add more black mass, the microbes also die.”

The trick lies in what is being fed to the microbes before any black mass can be added for material recovery, said Dr Joseph Jegan, senior researcher at ERI@N.

In his five years of research, he has sought suitable microbes and fed them combinations of inorganic and organic substances, from ammonia sulphate to potato and sugarcane wastes.

“When I obtained the microbes five years ago, I trained them by experimenting with the ratio of the different nutrients that they would need to produce metabolites and survive for a long time, especially in unfavourable conditions like high acidity and concentrations of heavy metals,” he said.

Prof Madhavi said such a way of recycling lithium-ion batteries would tap less resources than mining raw materials. She pointed out that to produce a tonne of lithium by traditional mining, 250 tonnes of lithium ore and 750 tonnes of brine would be needed.

To produce the same amount of lithium through the bioleaching process would require only 28 tonnes of spent lithium-ion batteries.

Energy is also saved because the microbes require 40 deg C for the recycling process. In comparison, the pyrometallurgical method heats up the spent batteries to over 1,000 deg C, which produces hazardous gases and greenhouse gases.

As raw materials such as lithium, manganese, cobalt and nickel may not be widely available globally, resource recovery to produce lithium-ion batteries can help secure certainty for cleaner energy sources and transport from electric vehicles, said Prof Madhavi, who is also co-director of the Singapore-CEA Alliance for Research in Circular Economy.

“If you’re able to recover these elements, then it makes a totally new market or a totally new paradigm for this concept of circular economy,” she added.