Published on 9 February 2023

A hero of Infectious Diseases: Wu Lien-Teh

Professor Joseph Sung

Dean, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine

As the shadow of COVID-19 is retreating, the World is gradually going back to normality, after three long years of turmoil. Although a few realise it, much of what we faced in COVID is a replay of what happened 110 years ago during the Plague – a deadly infectious disease outbreak caused by a bacterium.

During that pandemic that struck Asia in 1910, the hero was a brilliant bacteriologist Wu Lien-Teh, whom one of LKCMedicine’s houses is named after. He was tasked to deal with the Manchurian pneumonic plague of 1910 – 11. Born in Malaya, the son of Ng Khee-Hock was a Penang born Hakka. Because of his academic excellence, he was amongst the first groups awarded the Queen’s Scholarship in 1886, and at the age of 17, he enrolled in the famed Emmanuel College of Cambridge University. Wu obtained a First Class in his Bachelor of Arts final examination and was made a Foundation Scholar with a stipend of 60 Sterling Pounds. Wu was then offered to read medicine by St. Mary’s Hospital London where he won a series of prizes: Special Prize in Clinical Surgery, Kerslake Scholarship in Pathology and Cheadle Gold Medal for Medicine. He then worked briefly in Brompton Hospital (the famous Chest Hospital in London), and did research in Emmanuel College.

His interest in Infectious Disease was intensified when he spent a few months in the Tropical Disease Institute in Liverpool before he left England in 1903. He spent eight months in Germany’s University of Halle (now called Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg) under the supervision of the famous German bacteriologist Professor Karl Franekel. Then he moved to Institute Pasteur in France working under Professor Ellie Metchikoff. Wu then returned to Cambridge University, worked on his doctoral thesis and obtained his MD degree at the age of 24. However, as university regulations stipulated that there should be a minimum of three years between the first medical degree (MBBS) and the MD, Wu was conferred the MD two years later in absentia in 1905.

In 1903, Wu returned to Malaya, stopping by Singapore for a week, before returning to Penang to visit his parents. In 1904, he returned to Penang and established a private medical practice on Chulia Street. During the short visit to Singapore, he met his wife Ruth Shu-chiung Huang, whose sister was married to Lim Boon Keng. Lim himself was a medical doctor and Singapore’s first Queen’s Scholar; he promoted social and educational reforms in Singapore. (see Blog 15: “A doctor can do more - Lim Boon Keng”). Lim introduced Wu to the world of devoting one’s life to social services. Following the footsteps of Lim, Wu also played a prominent role in promoting women’s education, campaigned against opium smoking and gambling, and promoted physical exercise among youths.

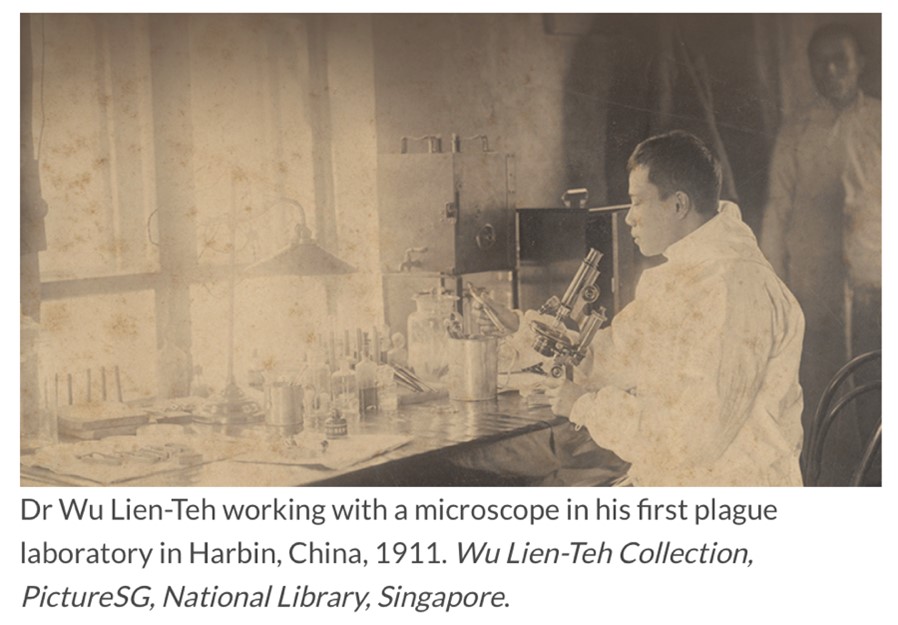

What Wu Lien-Teh is famous for really is his combat against pneumonic plague in Northeast China. The first plague epidemic started in 1910 when Wu was in Penang. General Yuan Shih-Kai (who later become President of China) offered the 29-year-old Wu the post of Vice Director of the Imperial Medical College of Tianjin. At around this time, a report came out from Peking that people in Harbin in Northern Manchuria developed a mysterious illness. Those who contracted the disease developed high fever, a cough and blood-streaked sputum, and later purplish discolouration of the skin. Almost all died within a few days. Wu arrived in Harbin on Christmas Eve 1910 during which temperatures were at minus 30 degrees. Russian doctors suspected bubonic plague was the culprit (spread by infected flea bites) and examined patients without a mask. They soon came down with the illness as well. As Chinese tradition then was to mourn and bury their loved ones, families of victims refused to provide bodies of the deceased for post-mortem. Finally, Wu got an opportunity to examine the body of a Chinese innkeeper whose wife was a Japanese. He cut open the body of the deceased and found Yersinia pestis (the plague bacterium) in the body as evidence of pneumonic plague transmitted by air through human contact.

Wu formulated a public health strategy that included putting a stop to travel (during the Lunar New Year), turning disused schools, warehouses and train cars into isolation facilities, mass cremation of bodies of the infected, and most importantly, recommended the use of face masks so that people could protect themselves from the droplets of infected persons. Wu’s plan met huge opposition from other experts in the field (e.g. a French professor Dr. Gerald Mesny); from families of the victims who refused to give up the corpses of their loved ones for mass cremation; from medical personnel who refused to wear masks; and from almost everyone against isolation. However, Wu managed to convince the government and handed down an order that all dead bodies were to be cremated as soon as possible, and all healthcare workers were to wear masks. Eventually, the containment measures started to show results and by 1 March 1911, there were no more cases of pneumonic plague in Harbin. In other Chinese cities, the outbreak lasted longer. Throughout the pandemic, a total stretch of 2,800 km cities from Manchuria to Peking were affected and in a period of seven months, an estimated 60,000 died. Wu, in his subsequent paper in the Journal of Hygiene published in 1923, pointed out that the gradual evolution of plague from the bubonic form into pneumonic form was a result of promiscuous spitting and huddling together of labour workers day and night in unventilated inns. Wu was very proud of the cotton-and-gauze masks that he promoted. He was the first Malayan nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935.

Does the story of Wu spark any ideas in you? What could be your thoughts? That medical research is worthwhile because its findings can save thousands of lives? Public Health is as important as clinical medicine because it formulates policies that could have huge societal impact? Or that success often hides behind numerous challenges and hurdles that those with a faint heart will not see? How about: where you come from should not be a limit to success in your career?