The key to financial sovereignty lies in the development of Capital Markets

What learnings can Africa take from India?

By Amit Jain

The global financial architecture, for most part, does not adequately address the development needs of the global south. Rising cost of development, limited fiscal space and intensifying great power rivalry between China and the United States, poses significant challenges for India and Africa in securing their development needs and maintaining economic sovereignty.

While India has traditionally relied on a mix of domestic savings, taxes and diaspora remittances to finance its development most African countries have relied on external borrowing and official development assistance (ODA) to do the same. Neither has been particularly successful in galvanising Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) either. This has left large gaps in their capacity to finance critical infrastructure, education, health and other public good. The problem for Africa has been particularly acute. ODA has been sharply cut in recently years, FDI is concentrated in the resource extractive sector and the recent hike in global interest rates has made borrowing from international markets significantly more expensive. While most developing Asian countries pay 5% interest on a bond, African governments have to pay twice as much. On Average African countries spent 16.7% of government revenue on interest payments and at least 30 of them spend more on debt servicing than public health. If that was not all, the strategic competition between the US and China has led many African leaders to green light unsustainable projects and sign resource backed infrastructure financing deals that threaten to undermine national sovereignty.

Navigating a fragmented global financial landscape

There was a time when emerging markets could access the global financial markets with abandon. Interest rates were low and hedge fund managers made fat bonuses investing in emerging market bonds and equity. There was too much liquidity in the international market, and it was landing up on the shores of India and Africa – two fast growing markets with working age populations bursting at the seams. What followed was nothing short of an economic boom. But all that changed in 2022. Russia invaded Ukraine and the era of cheap capital came crashing down. Rising commodity prices, spurred inflation and the Fed hiked interest rates, not only pulling investment out of emerging economies but also causing their currencies to depreciate.[1] All this has driven up the cost of borrowing capital for emerging markets. The willingness by the West to use sanctions, tariffs and financial action to compel Global South countries to do their bidding has created conditions ripe for the fragmentation of the global financial landscape. The BRICS group of nations have been toying with the idea of creating an alternative financial architecture. Some have even floated the idea of a BRICS currency as an alternative to the US dollar. The so-called de-Dollarisation of world trade is now no longer a fanciful idea as it may once have seemed. Nor is the use of the Chinese Yuan (CNY) of the Indian Rupee (INR) as alternative hard currencies. The CNY is reportedly already used in 50% of intra-BRICS trade and 18 countries have adopted the Special Rupee Vostro Accounts to make trade settlement with India. Seven of these are African.

There are important lessons worth drawing from this fragmentation of the global financial order. The first, is that neither Africa nor India are important actors in the world today. Their relative insignificance in global trade (3% or less), manufacturing prowess (17% of the GDP or less), and ideological weakness makes them vulnerable to great power politics. At the time of writing this article both were reeling from the slapping of tariffs on exports to the US. Second, at times of uncertainty, capital tends to bolt for safety. In 2024, for instance, foreign institutional investors (FII) started pulling out of India and other emerging markets as US interests rose. Third, unchecked illicit financial flows can be debilitating to economic development. Africa loses as much as US$90bn a year due to illicit financial outflows.[2] Neither Africa nor India can therefore depend excessively on external sources of finance. That brings me to the third most important lesson. Self-reliance. If they are to avoid becoming subordinates in an increasingly fragmented world both India and Africa would have to mobilise more domestic resources to finance their development. One way to do that is to develop a deeper, more liquid capital market.

There are important lessons worth drawing from this fragmentation of the global financial order. The first, is that neither Africa nor India are important actors in the world today. Their relative insignificance in global trade (3% or less), manufacturing prowess (17% of the GDP or less), and ideological weakness makes them vulnerable to great power politics. At the time of writing this article both were reeling from the slapping of tariffs on exports to the US. Second, at times of uncertainty, capital tends to bolt for safety. In 2024, for instance, foreign institutional investors (FII) started pulling out of India and other emerging markets as US interests rose. Third, unchecked illicit financial flows can be debilitating to economic development. Africa loses as much as US$90bn a year due to illicit financial outflows.[2] Neither Africa nor India can therefore depend excessively on external sources of finance. That brings me to the third most important lesson. Self-reliance. If they are to avoid becoming subordinates in an increasingly fragmented world both India and Africa would have to mobilise more domestic resources to finance their development. One way to do that is to develop a deeper, more liquid capital market.

Developing a liquid domestic capital market

A well-regulated capital market is arguably the best available means to channel domestic private savings into productive sectors of the economy. Capital markets mobilise finance and diversify investor. Economies with stronger capital markets experience less volatile credit cycles. Capital market makes it possible to pool small savings into bigger investments. The wider the participation of citizens in the capital market, the lesser is the need for the state to rely on foreign borrowings for development. India today is a US$4trn economy backed by a liquid capital market. Last year domestic retail investors poured in US$8bn into the Indian equity market on the even as foreign institutional investors pulled out.[3] India has been able to raise hundreds of billions of dollars from its domestic capital market. It raised over US$10.8bn through infrastructure bonds in the fiscal year 2024-25 alone.[4] Indian firms raise more than 80% of their capital requirement in the domestic market.[5] There is no reason why Africa could not do the same.

Recommendation

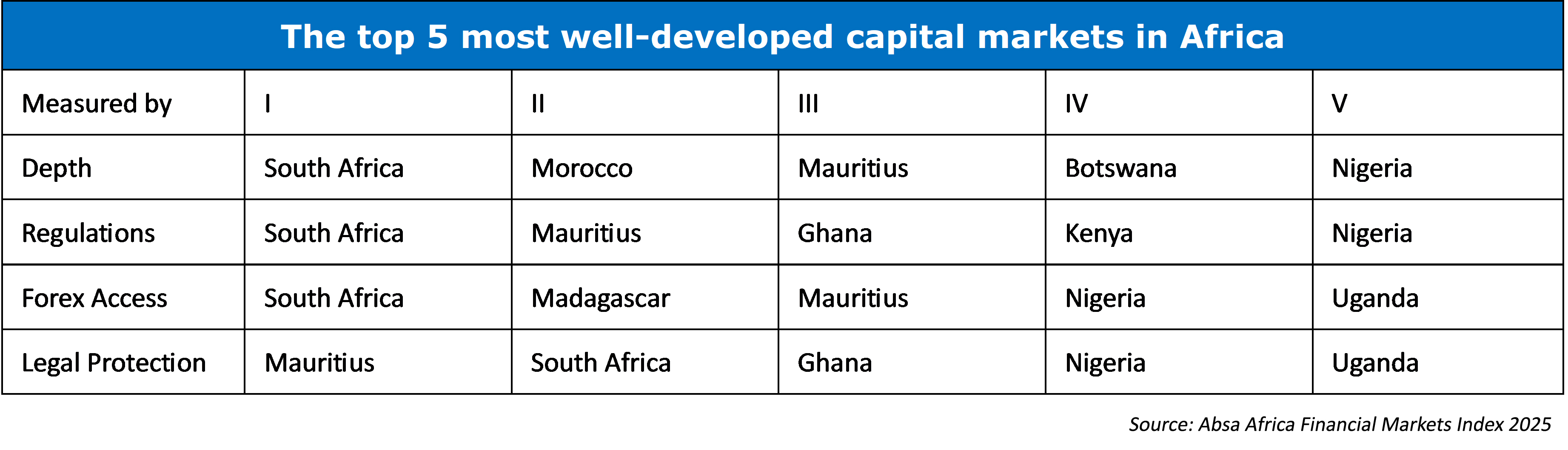

Start with the US$ $2.3trn worth of investment funds, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds that are locked overseas.[6] These could be ploughed back home if the African capital market was deeper and much more integrated. The problem is that the financial landscape of Africa is rather fragmented. There are 29 stock exchanges on the continent have a total market capitalisation of US$1.6trn. South Africa is by far the most liquid and deep capital market in Africa. The size of its equity capital market alone is US$1.1trn - nearly three times its GDP. Compare that with the Indian stock market capitalisation of US$5.5trn.[7] The ability to borrow through financial markets is viewed by investors as a sign of competitiveness. The success of the African Exchanges Linkage Project (AELP) – a pan-African experiment aimed at unifying seven regional stock markets - could, therefore, be a game changer. Facilitated by the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), which enables near-instant cross-border payments in local currency, the AELP could potentially consolidate the entire financial trading marketplace of the continent and end dependency on external funding. That sounds promising until you consider what it takes to develop a vibrant well-functioning capital market.

First and foremost, the expansion of capital market is related to economic growth. When the economy grows, households have more disposable income, as well as savings. Such savings make the pool of capital that can be channelled into productive investments in capital markets. Economic growth also expands business opportunities and that generates the demand for financing from firms that seek to tap those opportunities. The sustained three decade long economic boom that India has witnessed has been a key factor for the expansion of its capital market. For Africa, the expansion of capital markets could similarly serve as a catalyst for economic growth, job creation and wealth. It will help African governments raise capital domestically and make repayments in local currency. It will help African firms seek capital for growth, innovation and R&D and eventually lift their productivity and competitiveness. Participation in the capital markets will help build a more resilient financial future for everyday Africans and provide a certain buffer against inflation.

Capital market development encompasses a broad set of policy measures, rather than isolated initiatives. This covers everything from policies that increase investable savings – such as a mandated provident fund to widening of the tax net and gradual formalisation of the economy. It also requires a strong regulatory environment that can instil confidence in the market. The financial regulatory environment in Africa for most part is largely weak and fragmented. The answer is not creating an all-powerful pan-African capital markets authority but harmonising regulations and establishing listing requirements that meet some minimum baseline standards. This could include developing pricing benchmarks, strengthening investor protection, and tightening disclosure rules. The governance standards set by the Securities and Exchange Board of India may not be a gold standard, but it is arguably ‘fit for purpose’ for developing economies. In India, the two primary stock exchanges are the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and the National Stock Exchange (NSE). While the BSE is one of the oldest stock exchanges in Asia, the NSE is known for its technological advancements and high trading volumes. Beyond equities, stock exchanges also facilitate trading in commodities, bonds, and derivatives, providing diverse investment opportunities. With the rise of digital platforms, trading has become more accessible, attracting both retail and institutional investors to participate in wealth creation and economic growth. Using digital tools and investor education Africa could leapfrog the growth cycle of mature financial markets. In theory, at least. For instance, African governments can create an environment that encourages the entry of new investors and improve market liquidity by issuing local currency bonds in multiple tenors. Capital market development will also require deep engagement with third-party information providers such as underwriters, credit rating agencies, and research analysts. India attracted US$25bn more in capital when it joined the JP Morgan emerging markets bond index. Indeed, in more ways than one, India can be viewed as a case study for Africa as it attempts to mobilise more domestic resources and reduce its dependence on external sources for capital.

Capital market development encompasses a broad set of policy measures, rather than isolated initiatives. This covers everything from policies that increase investable savings – such as a mandated provident fund to widening of the tax net and gradual formalisation of the economy. It also requires a strong regulatory environment that can instil confidence in the market. The financial regulatory environment in Africa for most part is largely weak and fragmented. The answer is not creating an all-powerful pan-African capital markets authority but harmonising regulations and establishing listing requirements that meet some minimum baseline standards. This could include developing pricing benchmarks, strengthening investor protection, and tightening disclosure rules. The governance standards set by the Securities and Exchange Board of India may not be a gold standard, but it is arguably ‘fit for purpose’ for developing economies. In India, the two primary stock exchanges are the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and the National Stock Exchange (NSE). While the BSE is one of the oldest stock exchanges in Asia, the NSE is known for its technological advancements and high trading volumes. Beyond equities, stock exchanges also facilitate trading in commodities, bonds, and derivatives, providing diverse investment opportunities. With the rise of digital platforms, trading has become more accessible, attracting both retail and institutional investors to participate in wealth creation and economic growth. Using digital tools and investor education Africa could leapfrog the growth cycle of mature financial markets. In theory, at least. For instance, African governments can create an environment that encourages the entry of new investors and improve market liquidity by issuing local currency bonds in multiple tenors. Capital market development will also require deep engagement with third-party information providers such as underwriters, credit rating agencies, and research analysts. India attracted US$25bn more in capital when it joined the JP Morgan emerging markets bond index. Indeed, in more ways than one, India can be viewed as a case study for Africa as it attempts to mobilise more domestic resources and reduce its dependence on external sources for capital.

The author is the Director of the NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies at the Nanyang Business School in Singapore. A shorter version of this article will be published in a report at a high level policy dialogue at the African Union.

References

[1] ‘Does monetary tightening in advanced economies spell trouble for emerging markets?’ 11 Nov 2022, Deloitte

[2] UNECA 2025

[3] ‘Indian stock market set for record yearly flows from retail investors,’ Bloomberg NSE, 30 Dec 2024

[4] ICRA

[5] World Bank

[6] AFDB

[7] ‘India's total market cap touches all-time high of $5.5 trn for first time,’ Business Standard 30 Jul 2024

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)