Taking a closer look at Singapore Egypt economic ties

Bilateral trade has been sliding since 2001, but can this trend be turned around?

By Ronak Gopaldas

Ties between Egypt and Singapore stretch back 60 years, to when Egypt became the first Arab country to recognise Singapore’s independence.(1) Since then, the two nations have hosted numerous state visits between them, the most recent of which was in September of this year when President Tharman Shanmugaratnam of Singapore visited Cairo. The two sides signed no less than seven Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) across multiple industry and economic sectors.(2) These include maritime transport, small and medium enterprise development to health, government capacity building and agriculture. The visit came at a time when Egypt is undergoing a once-in-a-generation transformation, emerging as a prime market for business expansion, trade partnerships, and investment exploration. As Africa’s third-largest economy and a leading recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) Egypt is rapidly positioning itself as a regional hub for logistics, infrastructure, and urban development. This piece will take a deeper look at the potential of these agreements and examine which sectors stand to gain most from the increased economic cooperation and investment, and what a deepening of ties may mean for their respective economies.

Trade and investment in turbulent times

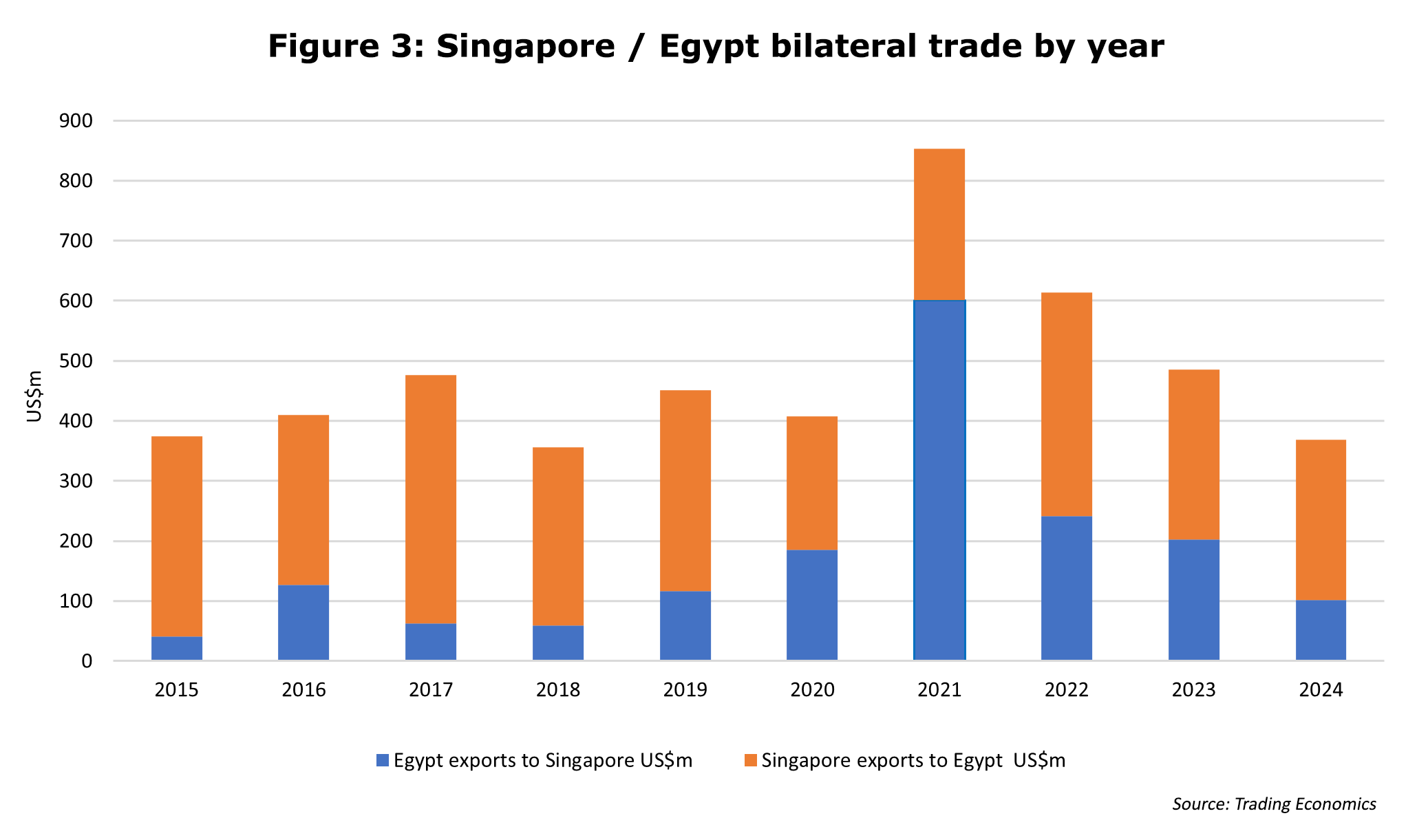

Bilateral trade between Singapore and Egypt amounted to US$360m in 2024, with Singapore’s FDI stock in Egypt totalling US$700m last year with investments from 129 Singaporean companies.(3)

Bilateral trade between the two nations peaked in 2021(4), but has been steadily declining since. The latest available data for 1H2025 shows that Egyptian imports from Singapore more than halved to US$125 from US$306 in 1H2024 (figure 3).

Bilateral trade between the two nations peaked in 2021(4), but has been steadily declining since. The latest available data for 1H2025 shows that Egyptian imports from Singapore more than halved to US$125 from US$306 in 1H2024 (figure 3).

There are a variety of factors that have led to the decline, among them broader regional instability in the Middle East, trade disruptions in the Red Sea, and Egypt actively looking to diversify its trade relations. Chief among them, however, are the wider fiscal and economic challenges Egypt has been navigating since 2023, the roots of which lie in longer-term, unaddressed structural economic imbalances.

There are a variety of factors that have led to the decline, among them broader regional instability in the Middle East, trade disruptions in the Red Sea, and Egypt actively looking to diversify its trade relations. Chief among them, however, are the wider fiscal and economic challenges Egypt has been navigating since 2023, the roots of which lie in longer-term, unaddressed structural economic imbalances.

From large trade and fiscal deficits driven by external debt-fuelled public infrastructure investment to high inflation, soaring interest rates and foreign currency shortages, Egypt has had to reach out for help.(5) The country is currently under an IMF program (US$8bn rescue package) to liberalise its exchange rate(6), introduce greater fiscal prudence and implement structural reform.(7)

In response to these headwinds and a desire to exit the IMF program after 2026, Egypt has launched a new economic narrative centring on high-productive sectors from tourism and ICT to agriculture, energy, manufacturing and logistics.(8) Key to this is crowding in private sector participation (privatisation).

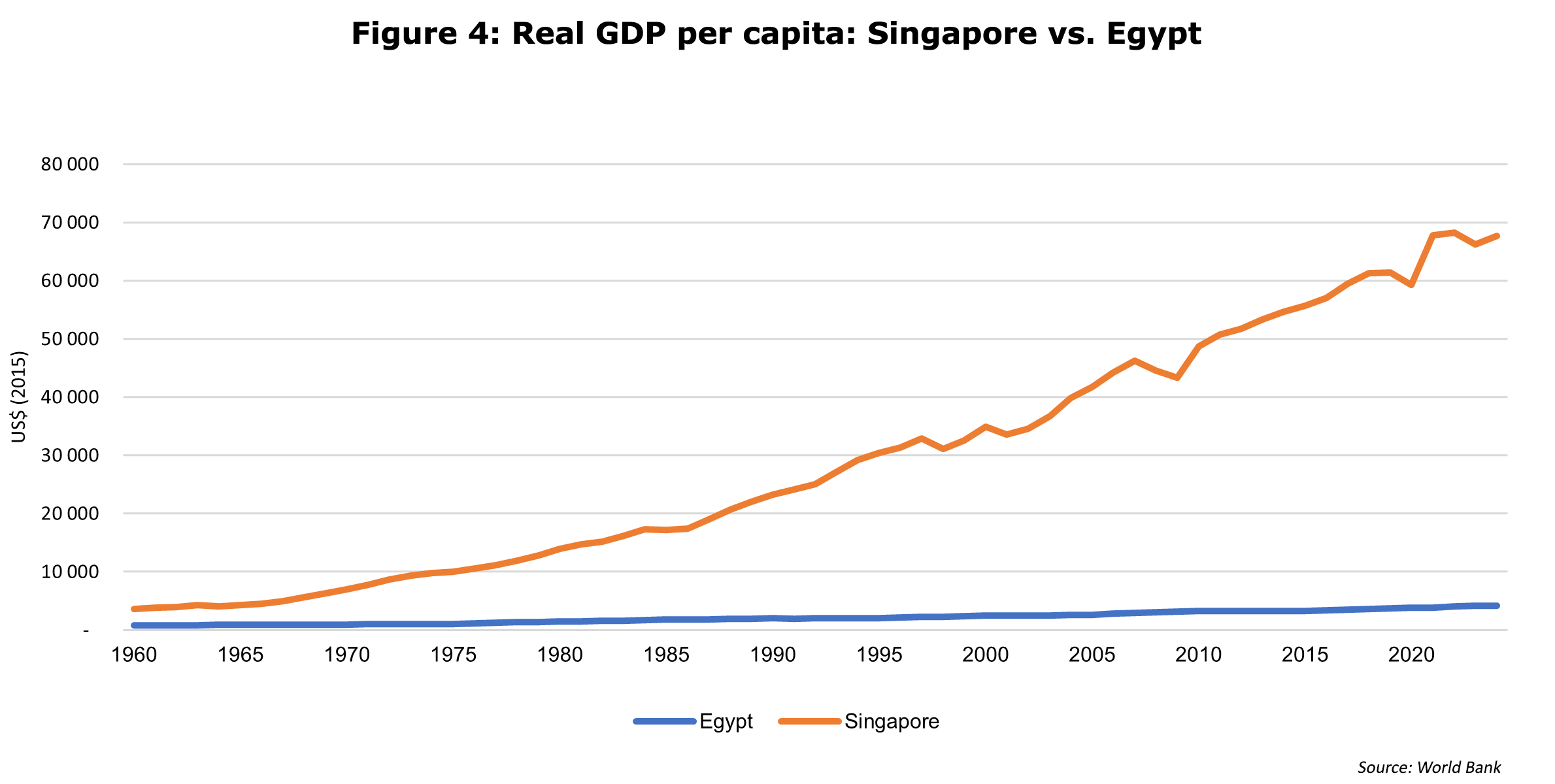

The challenges facing the Egyptian economy make the deepening of ties with Singapore all the more timely. Singapore has long been held as a model of what structural reform, a pro-business environment and active private-sector participation can achieve.(10) Since independence, Singapore’s real per-capita GDP has risen from US$4,215 (11) to US$67,700 (16x). Over the same period, Egypt’s per-capita GDP has gone from US$936 to US$4,138 (4.4x)[iv] (figure 4).

The development model adopted by Singapore rested on attracting foreign capital, investing in education, social development, building infrastructure, and following an open trading regime coupled with clean governance, predictable policies and rule of law. This transformed a small, underdeveloped island nation into the economic powerhouse that it is today. In short, Singapore has been where Egypt currently is and knows what it takes to turn an economy around.(9)

The development model adopted by Singapore rested on attracting foreign capital, investing in education, social development, building infrastructure, and following an open trading regime coupled with clean governance, predictable policies and rule of law. This transformed a small, underdeveloped island nation into the economic powerhouse that it is today. In short, Singapore has been where Egypt currently is and knows what it takes to turn an economy around.(9)

A hand up, not a hand-out

The MOUs and cooperation agreements signed by these two nations in September broadly align with the principles that laid a foundation for Singapore’s exceptional success and offer Egypt a valuable opportunity to partner with and learn from a world leading economic power.

- Maritime Field Cooperation

- Promoting Economic Partnership

- Cooperation in SMME and Startup Development

- Potential Cooperation in the Field of Social Protection

- Health Cooperation

- Agricultural Cooperation

- Cooperation in Training and Development of Government Capability

The first three; maritime(1), economic(2) and small business development(3), were all signed by Singapore Cooperation Enterprise (SCE), a state-run agency set up to share Singapore’s development experience with foreign governments. This knowledge sharing acts as a beachhead to private sector opportunities for Singaporean companies. It demonstrates the philosophy of shared experience (best practice) for shared prosperity which has not only been key to Singapore’s sustained momentum and success but delivered projects with revenue of US$50bn in just the last three years alone.(12) For Egypt, this collaboration will be invaluable in transforming its public sector into a leaner, more efficient entity positioned to drive Egyptian industry, exports and growth. Port and maritime logistics improvements are a key enabler of this vision.

Driving cooperation and enterprise

The latest Maritime MOU[v] signed between Singapore and Egypt is an extension of an agreement signed in 2015[vi] whereby the Port of Singapore Authority would assist Egypt in the running, operation and development of Egyptian Maritime Ports.(13)

As part of the new agreement, Singapore, leveraging its own experience of driving efficiencies and automating the Port of Singapore (and Tuas), will help with the digitisation and modernisation of West Port Said and conduct a feasibility study into converting it to a “smart port”.(14) More than just automation, the smart port will be able to provide real-time predictive data analytics, integrate artificial intelligence and introduce paperless customs and smart cargo handling at container terminals to reduce bottlenecks. A vessel traffic management system is also in the works to drive even greater efficiency, safety and cost savings.[vii]

Egypt has also expressed its desire to see Singapore investments in the Suez Canal Economic Zone(15) for the development of port terminals and bunkering services.(16) Already, Destiny Energy of Singapore has committed to investing US$210m in the country to build a green ammonia and hydrogen plant in the Suez Canal Economic Zone which will be powered by Destiny-developed wind and solar or existing renewable capacity.(17) Cooperation on a desalination plant has also been mooted.(18)

For Egypt and its ports, a crucial part of the agreement will be the training and upskilling of port officials and management, equipping them to implement global best practice. As a critical trade gateway between East and West, Egypt’s part in driving trade, time and cost efficiencies through the Suez Canal would have far broader spin offs for global trade and logistics well beyond Egypt (and Singapore). Additionally, the Suez Canal is an important revenue earner for Egypt and higher passage volumes, and lower costs through efficiencies would be an important boost for the fiscus. The Suez Canal alone facilitates 12% of global trade, reinforcing Egypt’s pivotal role in global supply chains. The US$ 58bn New Administrative Capital and nationwide smart infrastructure projects are also creating unprecedented investment opportunities for foreign investors in urban solutions, energy, logistics, and real estate.

Capacity building and digital transformation is also a key feature of the MOU(3) on cooperation in the field of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) and startups development. Singapore has a vibrant MSME ecosystem that is nurtured by state run agencies through funding, grants, tax breaks and incentives and mentorship and training. Singapore is ranked as the best startup ecosystem in Asia Pacific by the Global Startup Ecosystem Index, the fourth best in the world[viii] and was named the fifth most innovative country in the world[ix] in the 2025 Global Innovation Index. Much of these accolades have their roots in the supportive and nurturing environment the government provides small business enterprises, particularly ones with a focus on tech.

While Egypt provides considerable budget allocation (US$100m in 2025/26[x]) for the development of micro, small and medium sized enterprises (MSME), it currently lacks the coordination, focus and sophistication of the Singaporean model. The MSME MOU will use the blueprint of Singapore’s successful incubator program and industry sector focus to equip Egyptian government agencies to drive greater value and return from their investments while at the same time ramping up entrepreneur support and MSME success rates.

Similarly, the MOUs signed for social protection(4), health cooperation(5) and government training(7) focus on Singapore sharing best practice in building institutional capability and capacity for Egypt to better serve its development and economic agenda. The skills transfer and policy exchange will take place through various programs and fora with Egyptian delegates travelling to Singapore to understand their systems and processes and Singaporean experts travelling to Egypt to impart their experiences and practices.

The Institute of Technical Education (ITE) and the Civil Service College (CSC) of Singapore will consult on vocational training and a hospitality school project to help upskill institutions and workforces in key economic sectors as part of boosting the tourism sector, social services and women’s empowerment. The aim is to strengthen the public sector, governance and administration. The Singapore Ministry of Health will exchange experts on health services management, disease control, the digitisation of health information systems, aged care, research and medical biotechnology.

Overwhelmingly, the MOUs all have a strong bias toward human capital development, particularly in government. One of the more concrete MOUs signed, however, was that between Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory and Egypt’s Ministry of Agriculture who will jointly explore the growing of Temasek developed drought resistant rice cultivars on reclaimed Egyptian desert.(19) Food security is a key priority for both countries and successful trials, and ultimately full-scale production would be a significant boost to Egypt’s already considerable food and agricultural produce exports to Singapore.

Finally, the two nations have also agreed to explore the merits and feasibility[xi] of a Free Trade Agreement between the countries.(20) A Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) between the two countries has already been in force since 1997. While a FTA would be particularly pertinent in the current environment of heightened trade tariff uncertainty, negotiating a mutually beneficial agreement would take considerable time(21) since import duties from the country’s substantial purchases of Singaporean goods are a significant contributor to the Egyptian fiscus.(22)

Where the rubber hits the road

Egypt is by no means the first country Singapore has offered assistance to. SCE has a project presence in more than fifteen African countries (among them Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Namibia, Nigeria, Tanzania), and more than sixty globally, all with mixed success. Singapore’s guidance is overwhelmingly focused on upskilling, workforce development, public sector reform, government capacity building and urban development.

Egypt, whose economy suffered a sharp showdown from 2022-2024, appears to have bounced back. According to the IMF its economy will grow by 4.3% this year (2025) – almost twice the rate at which it grew in 2024. Its ability to leverage Singapore’s experience and lessons for growth and development will only ever be as good as the willingness to implement reforms and see them through. Singapore’s trajectory is a powerful illustration of what can be achieved, not when government gets out of the way, but when government paves the way for private sector investment and innovation. Ultimately, however, any plan (blueprint) will only be as effective as its implementation. The ball is in Egypt’s court.

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)