By Ronak Gopaldas

In a year where like-for-like global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell, FDI in Africa recorded a spectacular 75% jump in 2024 from the previous year.(1) It’s a headline grabbing performance to be sure, but one that doesn’t tell the full story.(2) Digging through the detail shows that while FDI in Africa remains positive, its lumpy, and its coming under growing threat.

In a year where like-for-like global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell, FDI in Africa recorded a spectacular 75% jump in 2024 from the previous year.(1) It’s a headline grabbing performance to be sure, but one that doesn’t tell the full story.(2) Digging through the detail shows that while FDI in Africa remains positive, its lumpy, and its coming under growing threat.

The basic pillars of investor confidence - political and policy predictability, currency stability, interest rate and funding conditions - are all at risk from rising geopolitical, economic and trade policy instability, not just on the continent, but globally. Uncertainty is the enemy of investment flows and in a highly uncertain global economic landscape, Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa in particular, will need to offer very compelling investment opportunities if it is to continue to grow development-enabling FDI.

African FDI in context

FDI inflows, investments to African economies from countries and multinational enterprises (MNE) outside the continent, reached a record high of US$97bn in 2024.(3) This contrasts sharply with an 11% fall in global FDI flows which declined to US$1.49trn from US$1.67trn in 2023.

A large part of Africa’s outperformance is a direct result of the Ras-El-Hekma megaproject (REH) in Egypt which added US$35bn to the continent’s 2024 inward FDI.(4) This joint venture (JV) between the Egyptian government and the United Arab Emirates’ Abu Dhabi Development Holding will see the construction of a mixed use (residential, commercial and recreational), next generation city along Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. The project is expected to be completed by 2030, create 100,000 jobs and attract as much as US$150bn in further investments to the Egyptian economy over its lifespan.(5)

Gulf investments in Africa have been a key theme over the past six years.(6) Large scale Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) investments have typically focused on ports and logistics which complement the Gulf region’s drive to become a nexus of global trade interconnectivity. The investment in Ras El-Hekma is a departure from this ambition and represents an expansion of interest into urban infrastructure, hospitality, leisure and tourism.

This single project investment accounted for three quarters of Egypt’s US$46.7bn FDI and more than a third of all FDI on the continent last year. To get a truer picture of the state of foreign direct investment in Africa, however, it’s important to strip out this significant once-off.

The simplest way to gauge the continent’s investment performance is to track its inward FDI as a percentage of total global FDI with and without the Ras El-Hekma project, and against its long-term average (figure 1). Doing this shows that inward FDI to the continent grew 12% y/y in 2024 (not the headline 75%), is above its 2010 - 2023 average of 3.5% of global GDP, and roughly in line with the 4.4% average since 2020. Hardly a step change in African inward FDI but a respectable performance, nonetheless.

Africa (+12%) and North America (+23%) were the only two continents to register growth in FDI inflows in 2024, with Europe (-58%), South America (-12%) and Asia (-3%) all contracting. Regionally within Africa, FDI inflows are relatively evenly distributed across the continent, with North and West Africa attracting the lion’s share of investment (half). East and Southern Africa accounted for a little under 40% of inflows, while foreign investment in Central Africa was largely driven by just three countries, the DRC, Gabon and Chad (figure 2).

Africa (+12%) and North America (+23%) were the only two continents to register growth in FDI inflows in 2024, with Europe (-58%), South America (-12%) and Asia (-3%) all contracting. Regionally within Africa, FDI inflows are relatively evenly distributed across the continent, with North and West Africa attracting the lion’s share of investment (half). East and Southern Africa accounted for a little under 40% of inflows, while foreign investment in Central Africa was largely driven by just three countries, the DRC, Gabon and Chad (figure 2).

Of these regions, West Africa was the only one to see a fall in overall investment growth (-7%) with all other regions growing by double digits.

On a country basis, there were notable investments in countries like Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Mozambique, Uganda and the DRC, all of whom attracted more than US$3bn in investments last year (figure 3).(7)

Despite the performance, the underlying data suggests that optimism for Africa’s FDI prospects over medium-term should be tempered.

Despite the performance, the underlying data suggests that optimism for Africa’s FDI prospects over medium-term should be tempered.

Investment clouds gathering

Foreign direct investment is categorised into three broad types:

- Cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

- Greenfield projects, predominantly industrial in nature

- International project finance (IPF), typically large-scale infrastructure projects.

Cross-border M&A typically accounts for around 15% of Africa’s annual FDI(8) and 2024 saw US$1.5bn of divestments from US$9.5bn inflows to the continent in 2023. This was mainly due to the sale of oil and gas assets by ExxonMobil in Nigeria. Cross-border M&A growth was positive in only east Africa, dramatically lower in southern Africa (nearly 90%) with the north and central regions of the continent also registering net divestments.(8)

The latter two FDI categories, greenfield projects and IPF, are announcement based and more forward-looking indicators of the investment pipeline.(8) Here, the news isn’t great either. North Africa was the only African region to register growth (12.1%) in announced greenfield operations, with west, east, central and southern Africa registering year-on-year contractions of -82.5%, -80%, -70.2% and -16.3% respectively. Announced greenfield projects were down 37% year-on-year for the continent which does not bode well for FDI over the medium-term. One bright spot was international project finance deals which increased 15% from 2023 but are likely to slow meaningfully in the coming years given heightened global economic uncertainty. The latest available FDI data for 2025 also suggests worse is yet to come.

Dealmaking activity in the M&A space for the first quarter of 2025 fell sharply to levels last seen during the global financial crisis.(9) Greenfield project announcements also registered record lows.

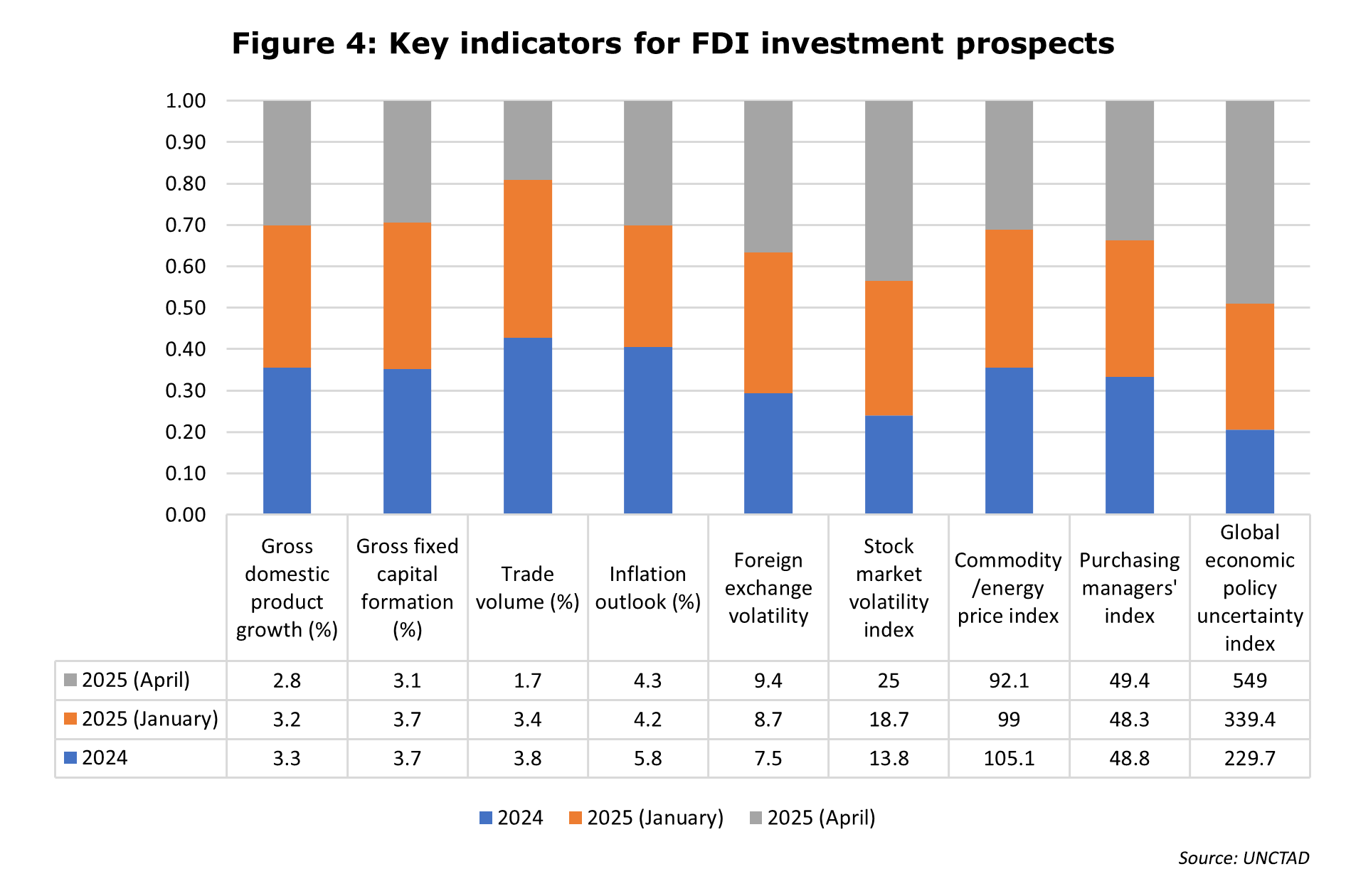

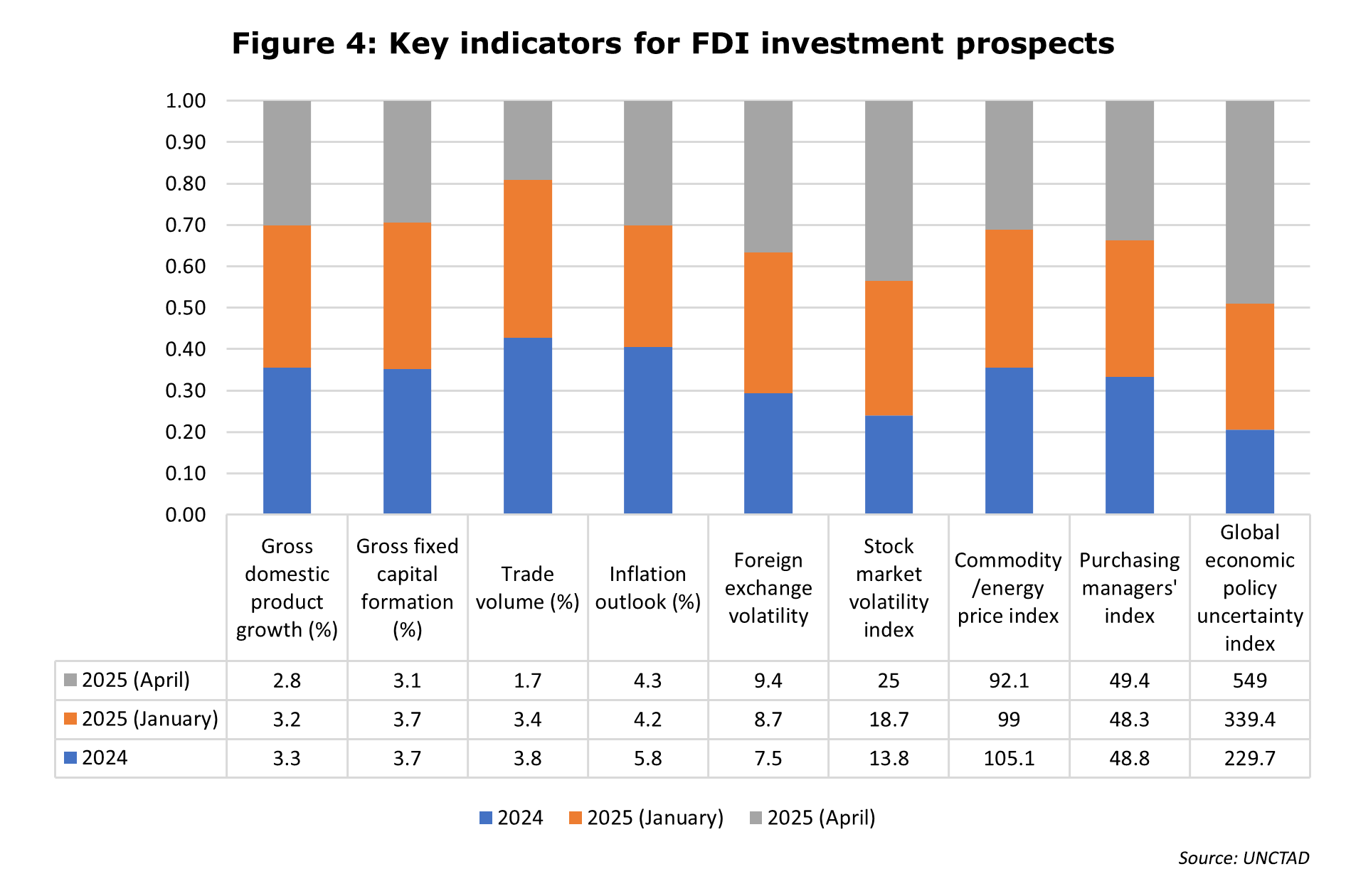

(9) Moreover, as highlighted in the 2025 World Investment Report, forecasts for the key drivers of FDI, global GDP, gross fixed capital formation, trade and forex stability, have all been downwardly revised since the beginning of the year (figure 4).

The dour medium-term FDI prognosis is sobering and confirms that the investment landscape has shifted. Global growth concerns on the back of a slowing Chinese economy and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East saw a sharp uptick in investor caution in 2024. 2025 started with even greater tumult and saw investor confidence battered further in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s trade relationships. Add in fears of higher global inflation and interest rates, and it’s understandable that many investors would rather take a wait-and-see approach until the dust settles.

The dour medium-term FDI prognosis is sobering and confirms that the investment landscape has shifted. Global growth concerns on the back of a slowing Chinese economy and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East saw a sharp uptick in investor caution in 2024. 2025 started with even greater tumult and saw investor confidence battered further in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s trade relationships. Add in fears of higher global inflation and interest rates, and it’s understandable that many investors would rather take a wait-and-see approach until the dust settles.Trade-offs: Tariffs will force an African rethink

August marked the end of Africa’s long-standing preferential trade agreement with the US (AGOA – African Growth and Opportunities Act). It is replaced by a blanket 10% import tariff for most goods sent to the US, with more than 20 African states being hit with higher tariffs of between 15% and 30%.(10) The implications for trade are bad but the impact on FDI will be just as detrimental. The US is one of the biggest investors in Africa by FDI stock, behind only the Netherlands and the United Kingdom(11), and the fifth biggest market for the export of goods made in Africa.(12)

Many multinational enterprises (MNEs) from around the world have invested heavily in African manufacturing facilities to take advantage of the AGOA agreement, which allowed them to export goods made on the continent to the US without duties to American buyers. Just one example is South Africa’s vehicle manufacturing sector.

German car maker, Mercedes Benz, set up a production plant in the country to produce vehicles for export to the US market. With these vehicles now subject to 30% import duties, Mercedes Benz may have to shutter its South African facility if it is unable to divert its products to new markets.(13) This would result in substantial disinvestment not just by the company, but by many of the smaller companies that supply into it, or that produce components for the US export market. In anticipation of the shock to US-Africa trade volumes, shipping company Maersk announced that it will only operate a single direct shipping line to the US from South Africa from October(14), with all other routes from South Africa to North America routed through European hubs.(15)

There are hundreds more examples(16) with smaller, less industrially diversified countries like Lesotho (textiles), eSwatini, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Namibia worse affected. The growing uncertainty will also likely put the brakes on new greenfield announcements as project finance gets more expensive and harder to come by, and investment risk appetite wanes.

Navigating the storm

How then can Africa offset, at least partially, the expected slowdown in FDI inflows to the continent, and likely wave of disinvestment it faces in the wake of higher trade tariffs and heightened global investment apprehension? There are a few levers it can pull, none of which will be easy, or yield short-term results.

Firstly, countries that can, should lean into their natural resource endowment, not just for investment in the extractive part of the value chain, but for downstream beneficiation. In 2024, nearly 15% of announced greenfield projects on the continent were in the extractive industries (figure 5). FDI in countries like the DRC, Uganda, Nigeria and Mozambique remain skewed toward mineral mining and extraction.

Despite beneficiation and the development of value-added products on home soil having long been a goal for African economies, progress has been slow. New investments in extractive sectors must entail some level of local value-add before goods are exported. The DRC (rare earth minerals), Mozambique (natural gas), Namibia (oil and gas), Angola (oil) and Zambia (copper) have all drawn substantial foreign investment for the exploration, extraction and production of minerals and commodities. Once these commodities have been mined, however, there are few, if any, economic benefits to the broader economy. Extraction must become a force-multiplier, and governments must do more to attract support industries for these extractive investments.

The DRC, in particular, has gained a great deal of foreign investor interest from the US, Europe and China recently due its large deposits of rare earth minerals such as lithium, cobalt and coltan which are used in battery technology. US and Chinese interests have spurred development of the Lobito (US$4bn from the US) and Tazara (US$1bn from China) railways which have also benefited the multiple African countries through which they each pass.(17) The spinoffs of these investments go beyond extraction and into infrastructure, energy and digital technologies and create thousands of employment opportunities.

Secondly, as with the development of rail corridors, African countries need to prioritise investments in support infrastructure such as energy, renewables, logistics and information and communication technologies (ICT) which have broader and longer-term economic benefits for the country. Several African countries are seizing opportunities for foreign ICT investment as a low hanging fruit (figure 6).

In this space, Ethiopia and Uganda are leading the way. Ethiopia has put tech investment front and centre of its FDI drive with the July ratification of the tech “Startup Business Proclamation”[i] which provides tax breaks, access to funding and other incentives for local and foreign investors in the sector, and which is already catching the interest of early stage venture capital and private equity firms from outside the continent.(18)

In this space, Ethiopia and Uganda are leading the way. Ethiopia has put tech investment front and centre of its FDI drive with the July ratification of the tech “Startup Business Proclamation”[i] which provides tax breaks, access to funding and other incentives for local and foreign investors in the sector, and which is already catching the interest of early stage venture capital and private equity firms from outside the continent.(18)

In Uganda, the government developed the ICT Sector investment plan in 2015[ii] which is bearing fruit. Fintech, ICT and digital economy investment is now the fastest growing FDI industry in the country. Tunisia, Nigeria, Kenya and Mauritius have created similar frameworks to encourage tech investment in their respective countries and more must follow suit.

In South Africa, global payments player, Visa, opened its first data centre in Africa in 2025 as part of a three year, US$60m investment in the country aimed at boosting the country’s digital economy.(19) Technology companies such as Alibaba, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Equinix and NTT all continue to expand their data centre presence on the continent(20), which is estimated only hosts 2% of the world’s data centres. With the rapid growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and the need for greater computing capacity to sustain this growth, Africa must position itself as a preferred location for data centres but will have to address its energy and connectivity challenges.

Between 2022 and 2024, FDI into software and IT made up almost 20% of total inward investments in countries like Kenya and Nigeria, with communications and media making up a further 8%, while renewables, alternative energy and metals and minerals adding 7% and 5% respectively.(9) Encouraging technology and ICT investment in Africa is a quick win as project implementation times are far shorter than capital intensive infrastructure projects which take years to realise.

There is another, often overlooked aspect of IT infrastructure FDI: between 2020 and 2023, it made up almost 50% of intra-regional greenfield FDI, with business services and software making up another 13%. As extra-regional FDI is expected to slow, intra-continental FDI in the digital economy, software, e-commerce, data processing, cloud and AI infrastructure investment can help maintain investment momentum, albeit not at the scale foreign investment offers. Currently, digital economy investments make up only 6% of total FDI on the continent but has become one of the fastest growing sectors with investment value in this sector up almost 75% since 2000 and project numbers more than 30% higher over the same period. Growth in digital economy investment in Africa is expected to grow sustainably between 10% and 12% over the next decade.

Finally, just like countries on the continent will have to expand current and build new trade relationships, it will have to do the same to attract new investment. The scale of intra-continental FDI pales in comparison to the value of inflows from outside the continent and Africa cannot go it alone. The end of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which allowed African products duty-free access to the US market will hit more than just trade. It will likely also see FDI from the US slow as many of the agencies in the US promoting African investment face severe funding cuts under the current administration. Large Chinese infrastructure projects have also slowed as that economy focuses more inwardly. To mitigate some of this impact, African states should actively court smaller, yet impactful investments from smaller eastern countries like Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea and Vietnam, all of whom already have an investment presence on the continent. While not the grand scale infrastructure and extractive investments many African countries have received from China, these smaller ASEAN countries typically target investments higher up the value chain in retail, manufacturing and services which are important economic multipliers. In this way, Africa can offset some of the anticipated slowdown from the US and China and drive economic diversification.

Africa is likely to undergo a period of adjustment in FDI patterns and in quantum as investor caution grows amid heightened global uncertainty. While still much needed, FDI in large scale infrastructure projects (ports, road, rail), energy and renewables are expected to slow as investors take stock of the impact of a vastly different economic landscape. Africa still has a great deal to offer foreign investors and should double down on attracting extractive investments as a gateway to broader, and conditional infrastructure FDI. It must actively pursue foreign investment in the technology space which acts as an important economic multiplier and court tertiary sector investments from smaller ASEAN countries who will find opportunity in the void left by the US and China on the continent. For Africa, it will be a difficult period of adjustment, but one that may leave it better economically diversified and positioned for sustained growth in the long run.

Citations and references.

In a year where like-for-like global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell, FDI in Africa recorded a spectacular 75% jump in 2024 from the previous year.(1) It’s a headline grabbing performance to be sure, but one that doesn’t tell the full story.(2) Digging through the detail shows that while FDI in Africa remains positive, its lumpy, and its coming under growing threat.

In a year where like-for-like global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell, FDI in Africa recorded a spectacular 75% jump in 2024 from the previous year.(1) It’s a headline grabbing performance to be sure, but one that doesn’t tell the full story.(2) Digging through the detail shows that while FDI in Africa remains positive, its lumpy, and its coming under growing threat. Africa (+12%) and North America (+23%) were the only two continents to register growth in FDI inflows in 2024, with Europe (-58%), South America (-12%) and Asia (-3%) all contracting. Regionally within Africa, FDI inflows are relatively evenly distributed across the continent, with North and West Africa attracting the lion’s share of investment (half). East and Southern Africa accounted for a little under 40% of inflows, while foreign investment in Central Africa was largely driven by just three countries, the DRC, Gabon and Chad (figure 2).

Africa (+12%) and North America (+23%) were the only two continents to register growth in FDI inflows in 2024, with Europe (-58%), South America (-12%) and Asia (-3%) all contracting. Regionally within Africa, FDI inflows are relatively evenly distributed across the continent, with North and West Africa attracting the lion’s share of investment (half). East and Southern Africa accounted for a little under 40% of inflows, while foreign investment in Central Africa was largely driven by just three countries, the DRC, Gabon and Chad (figure 2).

Despite the performance, the underlying data suggests that optimism for Africa’s FDI prospects over medium-term should be tempered.

Despite the performance, the underlying data suggests that optimism for Africa’s FDI prospects over medium-term should be tempered. The dour medium-term FDI prognosis is sobering and confirms that the investment landscape has shifted. Global growth concerns on the back of a slowing Chinese economy and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East saw a sharp uptick in investor caution in 2024. 2025 started with even greater tumult and saw investor confidence battered further in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s trade relationships. Add in fears of higher global inflation and interest rates, and it’s understandable that many investors would rather take a wait-and-see approach until the dust settles.

The dour medium-term FDI prognosis is sobering and confirms that the investment landscape has shifted. Global growth concerns on the back of a slowing Chinese economy and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East saw a sharp uptick in investor caution in 2024. 2025 started with even greater tumult and saw investor confidence battered further in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s trade relationships. Add in fears of higher global inflation and interest rates, and it’s understandable that many investors would rather take a wait-and-see approach until the dust settles.

In this space, Ethiopia and Uganda are leading the way. Ethiopia has put tech investment front and centre of its FDI drive with the July ratification of the tech “Startup Business Proclamation”[i] which provides tax breaks, access to funding and other incentives for local and foreign investors in the sector, and which is already catching the interest of early stage venture capital and private equity firms from outside the continent.(18)

In this space, Ethiopia and Uganda are leading the way. Ethiopia has put tech investment front and centre of its FDI drive with the July ratification of the tech “Startup Business Proclamation”[i] which provides tax breaks, access to funding and other incentives for local and foreign investors in the sector, and which is already catching the interest of early stage venture capital and private equity firms from outside the continent.(18)

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)