Africa’s water challenge

Despite its natural resource abundance, Africa is one of the driest continents on the planet, with nearly half its landmass considered dry and more than a third classified as hyper-arid or desert.

by Ronak Gopaldas

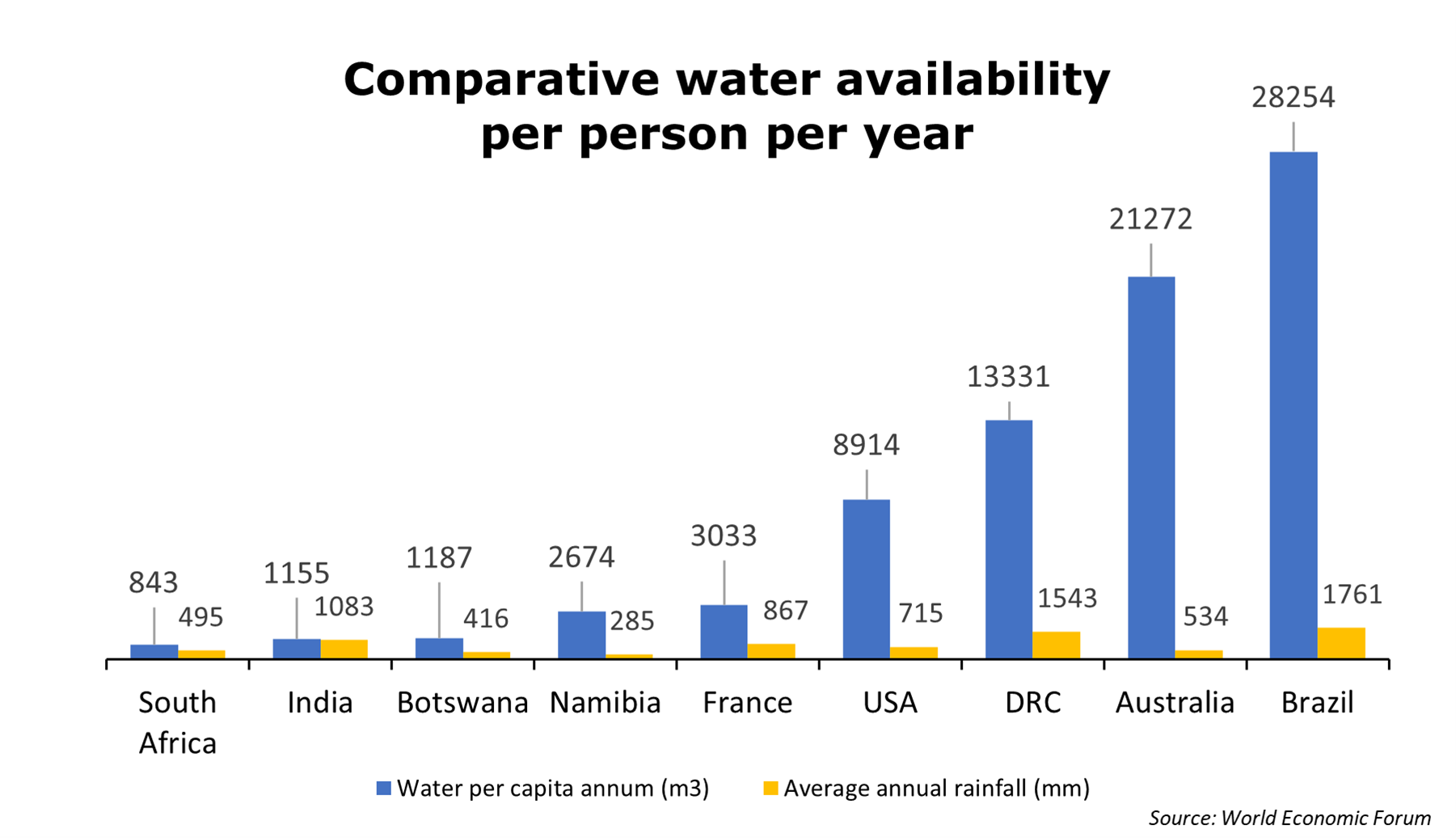

With nearly 20% of the world’s population and less than 10% of the planet’s water resources, access to sustainable clean water sources is fast becoming a matter of urgency both within countries and between nation-states.

Left unresolved, competition for this scarce resource threatens to spill over into domestic and regional conflict. The current tensions between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam provides a window into what could become escalating contestation for resources as a mix of policy mismanagement, complacency, pollution, and climate change accelerate the competition for water security.

With a focus on South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria, this article explores the current state of Africa’s mounting water challenge, how it got to this point and what needs to be done to ensure water access does not become a point of conflict on the continent. Finally, it unpacks the opportunities and challenges for the private sector and how the prudent management of resources can lead to greater economic prosperity for the continent.

- The mounting urgency of water security in Africa: An examination of South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria.

- How did it get to this point?

- The implications for African economies and industry.

- “Crowding in” private sector investments: Can it be done?

To many an observer, drought and famine are the first thoughts when considering the topic of water security in Africa. As the second driest continent (Australia is drier)[1], several African countries continue to experience severe water shortages, impacting food security, livelihoods, and economic growth. Water security, however, encompasses a far broader spectrum of risks.

The OECD measures a country’s water security based on:

- shortage (drought)

- inadequate quality (of water)

- excess (flooding)

- access (to safe water and sanitation)

On many of these scores, several of Africa’s biggest states are falling behind, jeopardising the likelihood of them meeting the sixth United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) which calls for ensuring the ‘availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.’[2] An audit of the progress of several African countries shows that significant or major challenges remain with 50% of them showing no progress in achieving SDG 6 targets (Table 1).

Table 1: Progress toward SDG 6

1. The mounting urgency of water security in Africa: An examination of South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria.

South Africa

South Africa’s ill-preparedness for a water emergency was brought to international attention in 2017 when Cape Town, a coastal city of more than four million people[3] braced for a so-called ‘Day Zero’ (11 May 2018) - the day the city’s taps were expected to run dry. After years of below-average rainfall the city’s groundwater levels had been depleted by a rapidly rising urban population. In the end, Cape Town city narrowly averted the eventuality through a mix of tighter regulatory controls and good fortune.

City authorities imposed stringent water consumption controls on households as well as businesses, which ultimately resulted in halving of daily consumption of water – 500m litres per day[4] and pushed ‘Day Zero’ further out into the future. A full-blown crisis was only averted, however, by a fortuitous high winter rainfall which raised water levels at the dam which had fallen below 15% to nearly full capacity in a matter of a year. Nevertheless, the economic damage had already been done. The drought is estimated to have cost South Africa 37,000 jobs, pushing more than 50,000 citizens below the poverty line.[5]

One particularly successful intervention was the reduction in water loss through maintenance and repair of its ageing infrastructure. The city’s water loss rate is currently 14% compared to the national average of 35%. Such high loss ratios in a low-rainfall country with deteriorating infrastructure and low levels of infrastructure investment due to severe fiscal constraints does not bode well for other regions. (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The neighbouring province of the Eastern Cape has experienced drought conditions since 2015 and it is estimated that the Nelson Mandela Bay coastal metro, one of eight metropolitan municipalities in South Africa, only has 1.5% usable water left for consumption.[6] In Johannesburg, the country’s economic hub, several hospitals had to function without water in May earlier this year after a power blackout knocked the city’s pump station out of action.[7] A charity group eventually stepped in to drill boreholes at two hospitals, averting what could have become a public health emergency. Protests, some violent are not uncommon in towns affected by a lack of basic service delivery as water infrastructure fails and communities are left without water for days.[8] While the country’s water challenges highlight government and municipal mismanagement and a lack of infrastructure investment, it also shows how proactive interventions, as well as private sector funding and expertise can quickly turn a potentially devastating situation around.

Egypt

Despite being one of the most water-stressed countries on the continent, or perhaps because of it, Egypt has made great strides in overcoming its water challenges. It is actually on track in meeting its SDG 6 goals (Figure 1). Nevertheless, water security remains an ever-present concern as its population grows and the economy improves. Classified as a country in water poverty (Figure 3), Egypt’s water demand is outstripping supply, which has remained steady, at 55.5 billion cubic metres for decades.[9] The annual water deficit that Egypt must cover is 30 billion cubic metres.

Figure 3:

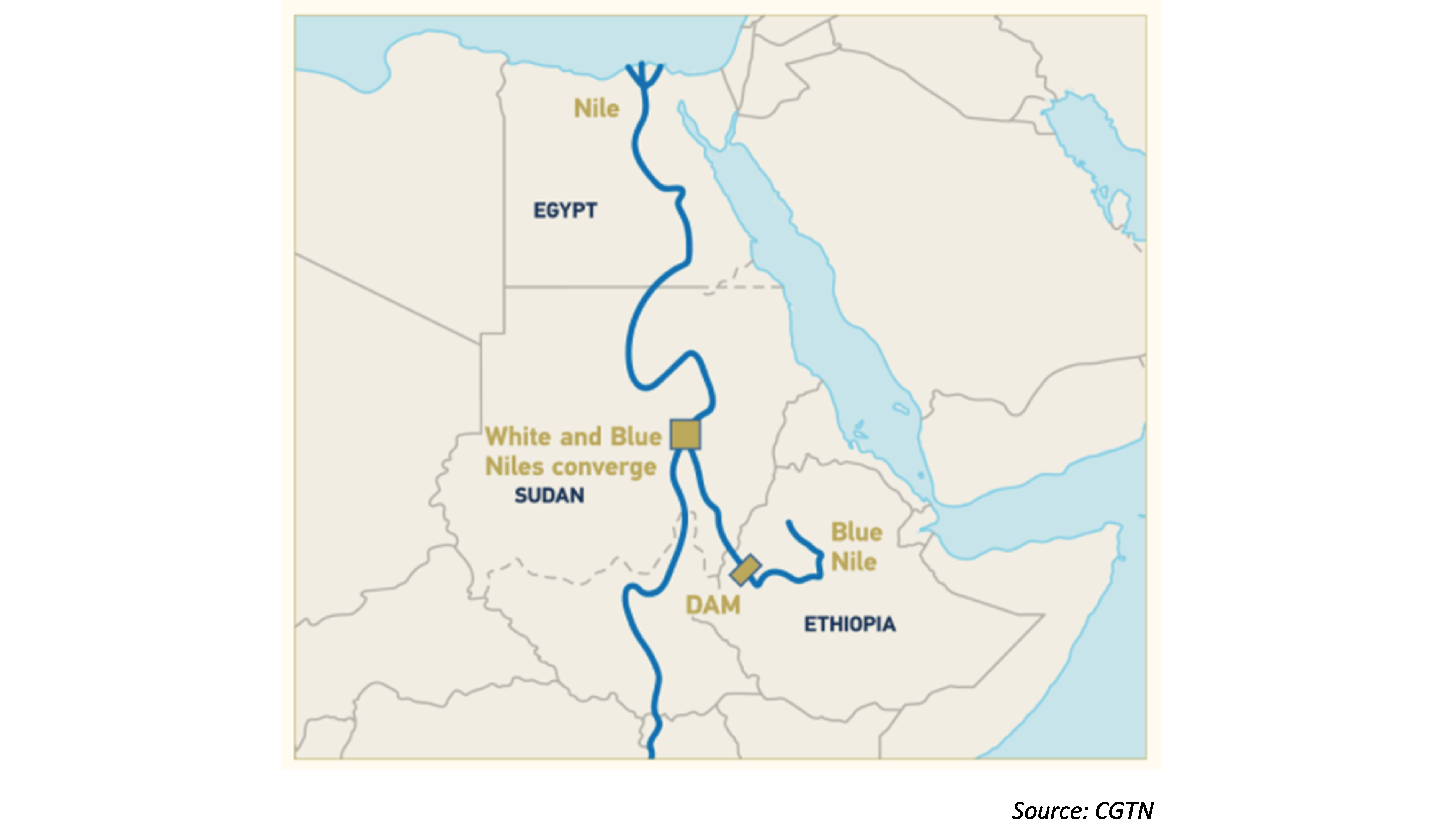

The country is heavily reliant on the Nile River for its water supply. A colonial-era treaty grants Cairo 90% control of the Nile river water. This has put it on a collision course with Ethiopia, whose plans for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in the upper-Nile is seen as a threat by the government of Abdel Fatah al-Sisi.[10] For Ethiopia and Sudan, the GERD is an equally strategic project - bringing in the much-needed water and (hydro) electricity required for their economic and industrial growth (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Position of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

While an agreement between the three countries on the way forward for GERD is still at an impasse, Egypt is proactively developing water infrastructure including additional desalination plants and catchment areas to harvest surface and flood water.

The GERD is far from the only contentious large-scale water project in Africa. The Grand Inga dams along the Congo River in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have the potential to generate nearly 40 GW of electricity making it the largest hydroelectric facility in the world. Plagued by delays, cost-overruns, and financial viability concerns, the project has also ensnared several private companies and nation-states in supply agreements that are mired in controversy and tainted by corruption.

In June, the Australian Fortescue Metals Group was granted exclusive rights to develop the US$100bn Grand Inga project[11], parts of which had already been committed to Chinese and Spanish companies. South Africa is another example. According to the WoMin African Alliance, the country’s offtake agreement with the DRC to procure 2500 MW of electricity from the project will cost utility provider Eskom an additional US$500m just to break even.[12] It will also allegedly create virtually no new jobs in the country.[13] Its report also found that other renewable sources could achieve better generating, financial and employment outcomes. Such mega-projects highlight the risks and complexities of doing business in Africa but also the enormous potential the continent holds.

Nigeria

Nigeria is rich in water resources, with an estimated 215 cubic Kms of water available for use annually. South Africa by comparison has only 49 cubic Kms.[14] Despite this, the country suffers from a dearth of safe, reliable, and accessible drinking water - a phenomenon known as “economic water scarcity”.[15] The term broadly refers to water shortages that happen because of shoddy infrastructure or poor management of water resources.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) found that 86% of Nigerians lack access to safe drinking water and one-third of Nigerian children (26.5m) do not have access to enough water to meet their daily needs.[16] Overall, while two-thirds of the population have access to a basic water supply, only 19% of Nigerians have access to safe drinking water.[17] Water-borne disease outbreaks such as typhoid, cholera, and hepatitis[18] are not uncommon and are the direct cause of more than 70,000 children under the age of five dying annually.[19]

Poor planning, lack of investment in sanitation infrastructure[20], growing population and rising pollution have all combined to make much of Nigeria’s water unfit for consumption. Dangerous levels of metal toxins are now found in the country’s drinking water.[21] Chemicals, pesticides, and waste often flow into rivers, polluting water sources and seeping into underground aquifers. Budgetary constraints from a treasury heavily dependent on oil revenue, and a seeming lack of urgency from the government have compounded matters. In May, the World Bank approved a US$700m credit facility for the country’s National Action Plan (NAP) to improve water supply, sanitation, and hygiene programmes. The plan has set a target of providing six million people with basic drinking water and 1.4 million people with improved sanitation facilities[22] over the next 13 years.

Nigerians have responded with remarkable ingenuity and initiative to deal with the clean water scarcity. Entrepreneurs and small businesses have stepped in to fill the market gap by providing clean water in sachets and bottles. Insurgent groups, however, have capitalised on the state’s failure to provide basic services to rally support for their cause. Even Boko Haram, the fanatical Islamic group which is particularly active in the north, is demanding the provision of clean water.[23] Time is running out for the government to begin addressing the country’s water challenges. Failure to do so risks growing social unrest, the continued rise of insurgent groups, and poses a broader threat to regional stability.

2. How did it get to this point?

To be sure, this is not just an African problem. Many regions around the world face the same challenges. While South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria all have region-specific causes for their water problems, there are several common threads: rapid population growth, high rates of urbanisation, insufficient (or inefficient use of) resources and the growing impact of climate change.

Africa’s overall annual population growth rate has remained stable at approximately 2.5% for the past two decades.[24] But the population of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has grown nearly 30% in just the last ten years.[25] Forecasts are far more worrisome. The continent’s population is set to triple by 2100.[26] A surge expected to be led by Nigeria whose population is set to reach 870m from 200m currently.[27] Over the same period, Egypt’s population is likely to double and South Africa’s to swell by almost 50% (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Table 2: Africa’s most populated countries

Rapidly rising rates of urbanisation are placing additional pressure on limited water resources and infrastructure investment has not kept pace with the increasing demand. It is easy to lay the blame on the government. Indeed, some criticism is justified. Poor planning, neglect, mismanagement, and corruption have all contributed to the problem. But private business and citizens must also accept their share of the responsibility.

Cape Town’s 2018 ‘Day Zero’ crisis proved that wasteful consumption of water can be cut down when businesses and citizens start to take responsibility. Water use for industrial usage and agriculture too can be far more efficient. The dramatic reduction in pollution due to reduced industrial, domestic, and tourist activity during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic shows that the effects of pollution can be reversed. Data taken from Vembanad Lake[28] and the Ganga River[29] showed dramatic improvements in water quality, all of which will be undone without the implementation of better water practices, waste management, and sanitation. Thus, the challenges to Africa’s water can be overcome and must urgently and proactively be addressed before the effects of climate change become even more severe.

Climate change is possibly the single biggest threat facing Africa’s water security. The continent is particularly vulnerable given low levels of adaptive capacity and high rates of poverty. The United Nations Environment programme estimates that up to 250m Africans are exposed to water stress as a direct result of climate change, which will increasingly bring droughts, floods, food insecurity, and economic hardship.[30]

3. The implications for African economies and industry

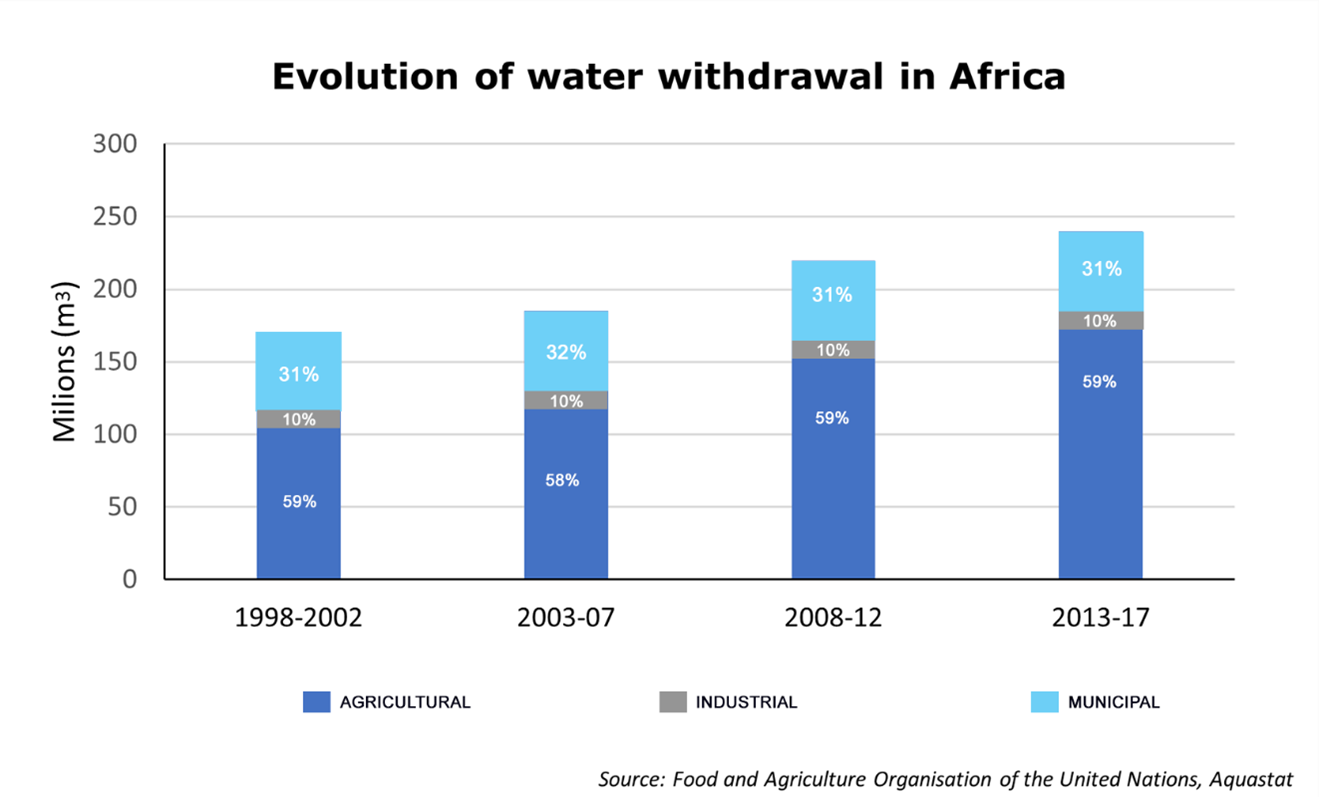

The greatest impact on usage will be felt at the municipal level and in the agricultural sector that together account for 90% of water usage on the continent (Figure 6). More than simply penalising wasteful and inefficient water usage, newer and more efficient practices must be implemented.

Figure 6:

Disincentivising consumption is usually done by increasing unit prices. But if not done carefully it can lead to widening the inequality that exists in water access. It could also be inflationary as often the higher costs are simply passed on to the end consumer. The most vulnerable communities must be protected from soaring water costs.[31] Countries can, however, mandate that taps in all new buildings be fitted with more efficient outlets (aerators) and smart meters with leak detection sensors. They can incentivise the collection and storage of rainwater and the use of “grey water” (a term used for domestic wastewater, excluding sewage) for irrigation. Similar measures can be applied to industrial users.

The biggest behavioural change will have to come from the agricultural sector, which is responsible for almost 60% of the continent’s water consumption. No government will want to compromise food security and export earnings but must work collaboratively with farmers and agricultural bodies to develop more water-efficient practices. It is estimated that improved rainwater and watershed management techniques in Africa could increase crop yields by two to four times.[32] Drip irrigation can reduce water consumption by up to 70% while newer technology to measure soil water content can prevent excess irrigation. Hydroponic farming which recycles water and greatly reduces the physical crop footprint while delivering higher yields is still in its infancy on the continent and African governments and organisations must encourage the participation and knowledge sharing of foreign firms with the requisite skills.

While industrial users only account for 10% of Africa’s water consumption they are the worst polluters sending harmful chemicals and toxins into rivers and streams, which eventually end up in the food chain. Policymakers will have to find the right balance between carrot and stick and should offer incentives to drive behavioural change and impose heavy penalties for non-compliance. Governments and industries across the continent must begin preparing now given the long lead-times for water project completion. Encouragingly, there are signs that governments are addressing the matter with some urgency.

In Egypt, local construction company, Orascom is building the country’s largest wastewater treatment plant in Cairo to address the needs of the agricultural sector, and as part of the Sinai Development Programme.[33] In South Africa, the National Department of Water and Sanitation has admitted that it does not have the financial resources to develop critical water infrastructure over the next ten years and has called on for greater private sector participation to, among other things, avert further economic and job losses in the agricultural sector.[34] The department has also recently established the National Water Resources Infrastructure Agency which is prioritising 11 water and sanitation infrastructure projects due to start over the next two years.[35] Lastly, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari urged the passing of the National Water Resources Bill by the National Assembly at the commissioning ceremony of the Zobe Water Scheme which will provide water for the irrigation of 2000 hectares of agricultural land.[36] He also called on the private sector to assist with funding and construction.

Africa would do well to tap the expertise of Singapore, a water-stressed city-state. Singapore has already overcome its water challenges and has made great strides in modifying consumption patterns and encouraging water conservation. The bulk of Singapore’s water comes from Malaysia under a contentious 1927 agreement, which is set to expire in 2061.[37] City authorities are, therefore, pre-emptively working to become self-sufficient in water. Singapore’s strategy is to diversify its water sources through rainwater harvesting, more efficient recycling, and the development of desalination plants. It has also invested heavily in the expansion of water catchment areas, better drainage, and changing consumer behaviour.[38] All of this has helped Singapore approach full water independence.

While it may seem like an insurmountable task for Africa, Singapore could also not envision that it would have come so far in such a short space of time. Paradoxically, Africa’s lack of infrastructure development may be its greatest opportunity. Most of Africa’s future cities have not yet been built. That means it has an opportunity to radically redesign urban infrastructure and make it water efficient.

It has not all been smooth sailing for Singapore though. Hyflux, the once high-flying Singaporean water utility is currently in liquidation after being crippled by US$2bn of unsecured debt and unable to agree to terms with creditors.[39] Singapore’s National Water Agency[40], Public Utility Board (PUB), recently took over the now-defunct company’s operations in Singapore after Hyflux defaulted on terms. The company once looked to Africa as a growth catalyst and in 2015 and won the contract to develop drinking and wastewater infrastructure in the Morogoro District of Tanzania. The project ultimately never took off due to delays and the ultimate demise of Hyflux, but the privatisation of water utilities across the world is facing strong pushback.

South Korea offers another approach. The country has been proactive in tackling water challenges posed by a rapidly expanding population, and limited water resources. It invested heavily in wastewater infrastructure, crowding in private sector companies like K-Water and building more than 100 wastewater treatment plants[41] while keeping user costs low and expanding access to all. Despite these investments, many Koreans remain wary of tap water after a phenol leak into the water supply in the 1990s and many households have built-in water purifiers manufactured by private Korean companies like Coway that make the bulk of their revenue from servicing water purifiers and selling replacement filters. Indeed, South Korea has seen large-scale private sector participation not only in the capital-intensive Build, Develop, Operate (BDO) space, but in the servicing of private households and companies.

4. “Crowding in” the local and foreign private sector: Can it be done?

Public-private partnership (PPP) and privatisation of inefficient state utilities are an often-vaunted solution to the government’s inability to deliver services.[42] This is, however, not always the case. In part, Nigeria’s water constraints are due to a longstanding impasse between the government, international funding agencies, and private water utility companies.[43] On its own, the government is unable to provide sufficient access to citizens of the country but has curiously pushed back strongly against industry privatisation citing profit motive.[44] For their part, funding agencies and private utilities have been unable to devise a funding and payment model that would make access to water cost-effective.[45]

Research by the Transnational Institute (TNI) shows that 180 cities across 35 countries have “re-municipalised” their water system in the past 10 years, both in developing and developed countries[46] (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Water utility re-municipalisations

The greatest obstacle to greater private sector participation in the water space is the cost of finance. There is also mutual distrust between governments and the private sector when it comes to managing public utility. This is not insurmountable. New technologies in the renewable energy space (power consumption is the single biggest cost factor in water desalination) and innovations in desalination, such as Hyflux’s proprietary membrane technology, mean that the cost of developing new infrastructure should come down in the future. Professor Shane Snyder, executive director of the Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute (NEWRI) at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University believes that the rapid development of water purification technologies such as the use of aluminium oxides, ceramics, and silicon carbide will rapidly reduce price points and greatly improve accessibility for smaller-scale water purification facilities that could be run privately and service limited areas cost-effectively, thereby negating the need for expensive large-scale projects. The decentralisation of water purification and supply could be an important pivot in water service provision in Africa and relieve funding and risk pressures for overstretched states. According to Snyder, less than 5% of purified water is used for human consumption. As such, he advocates for water recycling, where only water for human consumption is purified to the highest standard, thereby saving enormous expense, and generating far greater efficiencies in water supply.

What is, nevertheless, required are new and innovative funding structures that would make new projects digestible to heavily indebted African nations. It is estimated that the continent needs to collectively invest US$50bn per year to meet its longer-term water infrastructure requirements. Debt service costs and the payback periods will need to be dramatically reduced.

Blended financing models must be developed that incorporate project revenue, sovereign-backed funds, donor funds as well as insurance to lower the risk profile.[47] Various projects of differing risk profiles can also be pooled under a special purpose vehicle that would lower the funding costs of the riskiest projects and only marginally lift the cost of lower-risk investments. Climate funds, social and green bonds as well as government infrastructure debt all have a role to play in ensuring that Africa begins work on establishing greater water security. The capital-intensive nature and the limited financial resources in Africa make this approach all the more critical.[48] The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that the annual funding shortfall to meet the continent’s 2025 water security vision is between $54 and $45 bn and is actively driving engagements to secure financing.[49] The construction of a water treatment plant in Kigali, Rwanda, utilised funding from the AfDB, the Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund, and the Private Infrastructure Development Group through a mix of debt and equity instruments. Similar models have been employed in Morocco, Benin, and Malawi, as well as many other regions across the continent.

Figure 8: Blended financing approaches

The international private sector’s participation must not be consigned to just funding and privatisation. From expertise in dam building and water reticulation infrastructure development, to desalination plants, pumping stations and water sanitation equipment, there is ample opportunity for foreign investors to partner with and profit from water ventures.

Not only is water security a critical foundation for economic stability, but its sustainable management and equitable distribution can act as a catalyst for rapid economic growth and industrial diversification.[51] Inaction would be ruinous. As the impact of climate change becomes more pronounced, Africa has no alternative but to attract foreign investments in building its water infrastructure. Depending on their own unique conditions countries across the continent will need to diversify their water supply, introduce greater efficiencies through new technology and help chart a future that is water secure. If done right, private sector participation in Africa’s water future could be a goldmine, not a landmine.

References

[1] Schonberger, Steven. Advancing together toward water security and safely managed sanitation in Africa. World Bank. [Online] Novermber 9, 2018. https://blogs.worldbank.org/water/advancing-together-toward-water-security-and-safely-managed-sanitation-africa

[2] United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations. [Online] April 18, 2018. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

[3] World Population Review. Cape Town Population 2021. World Population Review. [Online] World Population Review, 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/cape-town-population

[4] Edmond, Charlotte. Cape Town almost ran out of water. Here's how it averted the crisis. World Economic Forum. [Online] August 23, 2019. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/08/cape-town-was-90-days-away-from-running-out-of-water-heres-how-it-averted-the-crisis/

[5] Baker, Aryn. What It’s Like To Live Through Cape Town’s Massive Water Crisis. Time. [Online] March 30, 2018. https://time.com/cape-town-south-africa-water-crisis/

[6] Ellis, Estelle. Eastern Cape crisis: Only 1.5% usable water left in Nelson Mandela Bay’s biggest dam. Daily Maverick. [Online] April 28, 2021. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-04-28-eastern-cape-crisis-only-1-5-usable-water-left-in-nelson-mandela-bays-biggest-dam/

[7] Heywood, Mark. Fire and no water: Johannesburg’s hospitals are in critical condition and need urgent help. Daily Maverick. [Online] May 24, 2021. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-24-fire-and-no-water-johannesburgs-hospitals-are-in-critical-condition-and-need-urgent-help/

[8] Ellis, Estelle. Eastern Cape: Panic and protests after Makhanda’s waterworks fail. Daily Maverick. [Online] February 23, 2021. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-02-23-eastern-cape-panic-and-protests-after-makhandas-waterworks-fail/

[9] Aziz, Mahmoud. Egypt's water challenges: Beyond the dam saga. Ahram. [Online] January 15, 2020. https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/359272/Egypt/Politics-/Egypts-water-challenges-Beyond-the-dam-saga-.aspx

[10] Egypt Today. Egypt's population to rise about 75 million by 2050: Water Minister. Egypt Today. [Online] June 5, 2021. https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/104692/Egypt-s-population-to-rise-about-75-million-by-2050

[11] https://www.mining.com/inga-hydropower-could-be-key-to-the-green-electrification-of-africa-report/

[14] Slaughter, Nelson Odume and Andrew. How Nigeria is wasting its rich water resources. The Conversation. [Online] September 5, 2017. https://theconversation.com/how-nigeria-is-wasting-its-rich-water-resources-83110

[16] UNICEF. Nearly one third of Nigerian children do not have enough water to meet their daily needs - UNICEF. UNICEF. [Online] March 22, 2021. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/nearly-one-third-nigerian-children-do-not-have-enough-water-meet-their-daily-needs

[17] Slaughter, Nelson Odume and Andrew. How Nigeria is wasting its rich water resources. The Conversation. [Online] September 5, 2017. https://theconversation.com/how-nigeria-is-wasting-its-rich-water-resources-83110

[18] Adeyinka Sikiru Yusuff, Wasiu John and Akintayo Christopher Oloruntoba. Review on Prevalence of Waterborne Diseases in Nigeria. Core. [Online] March 31, 2014. https://core.ac.uk/display/190320350

[19] Unicef. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. Unicef. [Online] 2001. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/water-sanitation-and-hygiene

[20] 7 in 10 Nigerian citizens do not have access to suitable sanitation.

[21] Slaughter, Nelson Odume and Andrew. How Nigeria is wasting its rich water resources. The Conversation. [Online] September 5, 2017. https://theconversation.com/how-nigeria-is-wasting-its-rich-water-resources-83110

[22] World Bank. Improving Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Services in Nigeria. World Bank. [Online] May 25, 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/25/improving-water-supply-sanitation-and-hygiene-services-in-nigeria

[23] King, Marcus DuBois. Water Stress: A Triple Threat in Nigeria. Pacific Council. [Online] February 15, 2019. https://www.pacificcouncil.org/newsroom/water-stress-triple-threat-nigeria

[26] Kazeem, Yomi. Africa’s population will triple by the end of the century even as the rest of the world shrinks. Quartz. [Online] July 16, 2020. https://qz.com/africa/1881468/how-fast-is-africas-population-growing/

[27] Prof Stein Emil Vollset, DrPH Emily Goren, PhD Chun-Wei Yuan, PhD Jackie Cao, MS Amanda E Smith, MPA Thomas Hsiao, BS et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. [Online] October 17, 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30677-2/fulltext?utm_campaign=gbd20&utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social

[28] Hijioka, Ali P. Yunusa Yoshifumi Masago Yasuaki. COVID-19 and surface water quality: Improved lake water quality during the lockdown. Science Direct. [Online] August 20, 2020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969720325298

[29] Sumita Singhal, Mahreen Matto. COVID-19 lockdown: A ventilator for rivers. Down to Earch. [Online] April 29, 2020. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/covid-19-lockdown-a-ventilator-for-rivers-70771

[30] Boateng, George. Saving our planet: Regional collaboration on effective climate change actions may provide answers. African Center for Economic Transformation. [Online] March 18, 2019. https://acetforafrica.org/media/blogs/saving-our-planet-regional-collaboration-on-effective-climate-change-actions-may-provide-answers/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI8uWgv5yx8QIVxAyLCh11LQNwEAAYASAAEgLvzfD_BwE

[31] Rogier van den Berg, Betsy Otto and Aklilu Fikresilassie. As Cities Grow Across Africa, They Must Plan for Water Security . World Resources Institute. [Online] May 11, 2021. https://www.wri.org/insights/cities-grow-across-africa-they-must-plan-water-security

[32] Sustainia. Water-Efficient Agriculture. Global Opportunity Explorer. [Online] June 26, 2018. https://goexplorer.org/water-efficient-agriculture/

[37] Reuters. Thirsty Singapore taps into innovation to secure its water future. The Hindu Business Line. [Online] June 7, 2019. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/world/thirsty-singapore-taps-into-innovation-to-secure-its-water-future/article27594282.ece

[38] WWF. Singapore water management: Water scarcity prompts water self-sufficiency. WWF. [Online] March 1, 2012. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?204587/Singapore-water-management

[39] Palma, Stefania. Court delays hit Singapore’s bid to be global restructuring hub. Financial Times. [Online] October 16, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/f67feebe-a87c-44f9-bfd7-577252b7b1c9

[40] Pangarkar, Nitin. The fall of once-great Hyflux, a unicorn in the Singapore story. Channel News Asia. [Online] March 8, 2019. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/fall-of-once-great-hyflux-unicorn-in-singapore-story-11320640

[42] Vidal, John. Water privatisation: a worldwide failure? The Guardian. [Online] January 30, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jan/30/water-privatisation-worldwide-failure-lagos-world-bank

[43] Oluwafemi, Akinbode Matthew. The Lagos Water Crisis: Any Role for the Private Sector? Urbanet. [Online] August 28, 2018. https://www.urbanet.info/nigeria-lagos-water-crisis/

[44] Obani, Pedi. Localizing the Human Right to Water in Lagos State, Nigeria. Utrecht Law Review. [Online] October 30, 2020. https://www.utrechtlawreview.org/article/10.36633/ulr.559/

[45] Hall, David. Nigeria - Water - Impact on Lagos water of WB privatisation plans, union response. Public Services International Research Unit. [Online] July 2010. http://www.psiru.org/node/15297.html

[46] Vidal, John. Water privatisation: a worldwide failure? The Guardian. [Online] January 30, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jan/30/water-privatisation-worldwide-failure-lagos-world-bank

[47] Global Water Partnership. Water Security in Africa: How Innovative Financing Can Enable Climate Resilient Development. Global Water Partnership. [Online] 2020. https://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/gwp-saf-files/innnovative-financing.pdf

[48] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/3b064c31-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/3b064c31-en

[51] Network of African Science Academies. The Grand Challenge of Water Security in Africa. Network of African Science Academies. [Online] 2014. http://nasaconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/The-Grand-Challenge-of-Water-Security-in-Africa-Recommendations-to-Policymakers.pdf

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)