How do Asian consumers determine which food is healthy?

This article outlines how Asian consumers approach the concept of health and nutrition in food choice making, compared to Westernised countries.

By May O. Lwin

This article outlines how Asian consumers approach the concept of health and nutrition in food choice making, compared to Westernised countries.

- Dietary habits across much of Asia have undergone substantial changes in the past 20 years as a result of economic growth, urbanisation and globalisation.

- Researchers indicate that as many as 50% of shoppers are seeking "health" when shopping for food but nutrition knowledge and literacy amongst Asian consumers is at much lower levels than for their Western counterparts.

- While Western consumers use prior product knowledge and nutrition labels, Asians often rely on highly visible external cues that are clearly seen (including pack design, product information, claims and advertisements) to determine whether food products are healthy.

- One of the key cues which Asians rely on are seals which appear in the front of packaging, and are usually awarded by a third party based on assessment of the product.

Asia has undergone tremendous changes in the accessibility of different food types as well as the way in which local food products are manufactured and distributed. This has presented major challenges for Asian consumers as they attempt to navigate new forms of retail, an unprecedented choice of food products and cuisines and all this in the face of a barrage of government communications about the rise of obesity, diabetes and the need to focus on individual health and nutrition. In such a confusing and rapidly evolving market, how do consumers in Asia determine what is healthy and what is unhealthy?

This article highlights some of the key trends shaping how Asian consumers approach the concept of health and nutrition in food choice making. It also describes how these changes offer opportunities for marketers to conceptualise and develop strategies to reach and satisfy consumers seeking healthy and nutritious benefits from their foods.

Asian food landscape

Dietary habits across much of Asia have undergone substantial changes in the past 20 years as a result of economic growth, urbanisation and globalisation. These dietary transformations among Asians have been been influenced by a number of key marketplace trends:

- Rise in availability of processed and packaged foods

- Increased access to non-indigenous food products

- Increase in Western and local fast food chains

- More women working, leading to less home food preparation

Asian food and food consumption has traditionally centred on health in terms of the use of natural ingredients, cuisines which balance dietary intakes, availability of freshly cooked meals and the use of local produce. In the past, these health-related concepts were typically communicated through word of mouth, family teachings and experiential learning – practices which are fast disappearing in the context of modern food consumption.

Daily meals in many parts of Asia are traditionally based around rice or noodles, with vegetables, optional meat and condiments all contributing to the dietary balance. Shopping at "wet markets" which sell fresh produce, was a daily activity and allowed Asian mothers to teach their daughters basic marketing skills, such as how to select seasonal fruits and vegetables. These skills were passed on from mother to daughter, with women traditionally undertaking the responsibility for shopping, food preparation and cooking. Today, with more women working, Asian women are spending fewer hours in the kitchen, and home-cooked meals are becoming far less prominent, especially in urban parts of Asia.

Rising economic prosperity has fuelled demand for greater convenience in food products and food preparation. Parallel to the loss of healthy food preparation in Asian kitchens is the rise in availability of many varieties of processed and packaged foods in minimarts and supermarts which in turn has given Asian consumers greater access to imported foods. Given this new food landscape, how do modern Asian shoppers decide what is healthy?

Researchers have shown a rising interest in health across Asia, with as many as 50% of shoppers seeking "health" when shopping for food. However, research has also revealed that nutrition knowledge and literacy amongst Asian consumers is at much lower levels than their Western counterparts, particularly when it comes to modern supermarket navigation. In the West, where supermarkets have existed for several decades, consumers have acquired knowledge and literacy about food items sold in supermarkets or convenience stores through both parental guidance and public education over generations. In Asia, on the other hand, traditional skills in conventional marketing have not transferred to modern supermarket environments. Hence Asian consumers are often challenged when it comes to deciphering nutrition cues from e.g. food labels, often located on the back of packs. Nutrition labels on packs originate from Western cultures and tend to utilise both numbers and English terminology unfamiliar to Asians (e.g. "iron, lactose, cardiovascular health"). Without specific nutrition label education, these forms of nutrition communication can become barriers to Asian consumers' assessment of health values in packaged foods.

Below are some of the key behavioural trends that have been observed amongst Asian consumers navigating the modern urban food settings in the recent decade.

Large dependence on external packaging

Without a long history of supermarket shopping knowledge, Asian consumers who are exposed to a baffling array of products on shelves attempt to utilise their traditional marketing skills when confronted with packaged goods. While Western consumers use prior product knowledge and nutrition labels to make choices, Asians often rely on highly visible external cues that are clearly seen (including pack design, product information, claims and advertisements) to determine whether food products are healthy. Some of these marketing signals can go beyond the central features of the packaging and are called "peripheral cues". Peripheral cues are less dominant features like the shelf position of the packaging, the physical weight and shape of the package or even the Country of Origin (COO) of the product.

One of the key cues which Asians rely on are seals which appear in the front of packaging, and are usually awarded by a third party based on assessment of the product. Below are some of the more common seals found on food products:

Singapore Health Promotion Board Seal of Approval: Indicates the "Healthier Choice"

HACCP Certification Seal: Indicates whether the food product is certified by HACCP.

Halal Seal: Indicates whether the food product is certified "Halal".

Fictitious seals are not true certifications issued by any governing authority but look like true seals. Examples:

Other types of seals that pinpoint to specific affiliations of foods. Examples:

In an experiment to test the impact of seals on food choice, our research team created two identical snack products: one with a seal which we manufactured to look like a real seal and another without. A group of Asians residing in Singapore aged between 18 and 36 years were then asked to rate these products on a number of dimensions. Unsurprisingly the pack which bore the fictitious seal fared significantly better in terms of perceived purity, wellness and healthiness of the product, suggesting that even an unfamiliar seal signifying an apparent endorsement by a public health authority confers perceived health benefits.

A subsequent experiment found that nutritional seals also contributed to a food product's perceived healthiness and naturalness of the ingredients.

Dependence on claims

In addition to external cues such as seals, Asians tend to look for explicit claims on the food products themselves. As a result there has been a proliferation of claims on Asian food packaging compared to products which originate in other regions such as North America and Europe. In the West, while consumers also read claims, they tend to be more experienced shoppers who also rely more on branding, nutritional label information etc. (typically at the side or back of packaging).

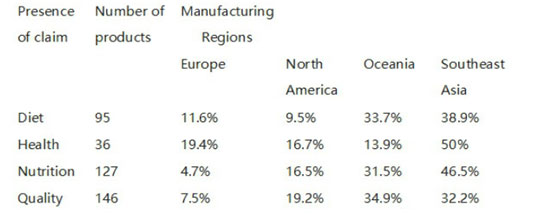

Below is a summary of the findings from our research which details the use of food label claims in different parts of the world.

Compared to Europe where less than 20% of products displayed health–related claims, in South East Asia, this figure rises to 50%. Similar differences in the use of claims were also observed for dietary, nutritional and quality claims.

Usage of food label claims in different parts of world

*Adapted from Lwin, May O. (2015) Ways of Eating, Ways of Being: Food Consumption and Representation in Asian Markets. Journal of Consumer Marketing.

In another study, to test the impact of food package claims on food choice, our research team again created two identical snack products: one with a "natural" claim on the pack and one without. A group of Singaporean consumers aged between 18 and 30 were then asked to rate these products on a number of dimensions. We found that consumers tended to generalise benefits beyond the claim itself. The use of the "natural" claim on a relatively unhealthy product prompted consumers to associate the product with other (unclaimed) health related benefits.

Convenience vs health trade-offs

Another facet of the modern Asian consumer is the growing desire for convenience despite its association with less healthy options. For example, the instant noodle phenomenon - a truly Asian convenience food - has become a staple diet in many parts of Asia. Yet many instant noodle brands in Asia continue quite openly include unhealthy ingredients such as MSG and colouring whereas in countries like Australia, these ingredients have been excluded in an attempt to make products more acceptable to health conscious Australians.

Modern Asian consumers, it seems, tend to place a higher value on convenience than healthiness. In Thailand, Philippines and Malaysia for example, convenience store penetration has risen at a much faster rate than any other retail platform. A recent study by the DBS group showed that across ASEAN, modern grocery retail grew at a staggering 12% compound annual growth rate between 2010 to 2015.

Speciality foods are treated differently

The same laissez faire attitude is also applied to speciality foods. Asians are inclined to place great emphasis on unique taste sensations and the overall food experience, and for such special meal experiences, health benefits are typically not a primary concern. When ordering a celebratory meal, the considerations would normally revolve around the symbolic nature of foods (for instance, noodles to signify long life) and the perceived significance to the host's status. Asians willingly spend much more time, effort and money locating and purchasing these food items, with little consideration of the health benefits. For example, long queues outside shops selling special Lunar New Year cookies, Hari Raya cakes and even the latest Japanese cheesecakes are common in urban and local malls.

Traditional concepts of health

When health benefits are sought by Asian consumers, there is still a strong tendency to refer to well-established traditional concepts of health. These are specific to indigenous cultures and cover an array of different philosophies such as Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurvedic or herbal medicines. Consequently, Asian consumers often seek evidence of traditional health benefits when purchasing food products and experiences. For instance, a modern food product might be perceived as healthy if it is perceived to have "cooling" (Yin) effects that balance the "Yang". Other products, such as those containing chicken essence, which is thought to provide energy, tend to be sought out and consumed by students during examination periods.

Implications

Food manufacturers who understand and adapt to the way in which Asians determine health benefits in foods have a clear opportunity to gain competitive advantage. One recommendation is for food companies to carefully calibrate if their products are indeed "healthy" and if so to provide clear explicit front-of-pack information supported by promotional materials such as brochures or website information to convey the key health benefit(s). Conversely, unhealthy products should refrain from attempting to mislead consumers via fluffy claims such as "natural" as this will lead to consumer confusion and eventual mistrust in marketing messages.

Another challenge for food marketers is to develop product benefits which are in sync, not just with Western concepts of health, but also communicate health benefits based on Asian notions. Market research, which informs marketers about indigenous notions of health in particular communities, is needed to develop and deliver culturally grounded messaging both in packaging and promotions.

For marketers, credible cues such as nutritional seals and clear health information based on scientific fact can be useful ways to assist consumers in making healthier food choices. For products from positively perceived countries-of-origin, highlighting these positive associations in product promotions can be advantageous. However, manufacturers need to exercise caution. Excessive use of claims on product packs can have the reverse effect, causing consumer confusion and an inability to perceive the real nutritional information.

Policymakers in Asia too, can benefit from these findings. There is clearly an urgent need to educate Asian consumers in food nutrition literacy, as well as how to read food labels correctly, so that consumers can make informed choice comparisons between alternative products. Education needs to start early, ideally in schools, as children today are making their own food choices in school canteens and local convenience stores. Government policies to prevent food manufacturers from posting confusing or unsupported cues on their food packaging will also help build closer relationships between global food brands and their new target audiences in the Asia-Pacific region.

About the author

May Lwin is an Associate Professor of Strategic and Health Communication at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication & Information, Nanyang Technological University and a Senior Fellow of the Institute on Asian Consumer Insight. She is one of the leading authorities on Marketing Communications in Asia. She has authored a number of marketing books, including the bestselling Clueless Series (Clueless in Advertising and Clueless in Marketing Communications).

This commentary was published in Warc Exclusive, January 2017.