Collaboration between behavioural psychologists and geoscientists to understand origin of stone tool use in long-tailed macaques

Imagine that you are born with a talent for swimming. Still, in order to get really good at swimming you also need to have access to swimming pool, good coaches, and having a swim team to join will certainly help. How good you get at swimming will depend on a combination of several factors; your ability to learn the skill, as well as your social and physical environment. Among wild animals, a skill or behavioral adaptation, such as monkeys using stone tools to crack open oysters, is also influenced by the social and ecological environment, for example: Is the group they belong to using tools? And is there plenty of yummy oysters around? But individuals may also differ in the way they respond to these environmental factors depending on an innate ability to pick up the skill; a learning bias or ‘talent’. A recent study led by animal behavioural psychologist Assoc Prof Michael. D Gumert from NTU’s SSS, in collaboration with ASE’s Assoc Prof Adam Switzer and PhD student Constance Ting Chua, integrates environmental and social processes with learning biases to explain why some long-tailed macaques use stone tools while others don’t.

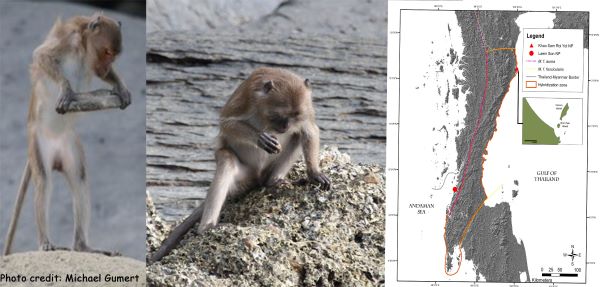

The study was possible thanks to the co-existence and interbreeding of two subspecies of longtailed macaques in coastal environments on the Andaman Sea of southern Thailand and southern Myanmar. One subspecies, the Burmese long-tailed macaque, uses stone tools to open and eat oysters and sea snails, spending as much as 41% of their foraging time on the coast doing so. The other subspecies, the common long-tailed macaque, almost never uses stone tools or feeds on molluscs. But where the two species interbreed, creating hybrid populations of mixed common and Burmese origin, the story is more complicated. This situation provides a unique opportunity to study the controls of animal behaviour in the wild.

So how come Burmese long-tailed macaques use stone tools? And why don’t common long-tailed macaques start making use of the marine food source when they encounter coastal environments? It turns out that in the hybrid populations, with shared ecological and social environments, how likely an individual is to use tools can be pretty well predicted by their physical appearance. Individuals that resemble the Burmese subspecies (in terms of hair around the face) are more likely to use stone tools, while individuals whose hair around the face more resemble the common subspecies, are less likely to use stone tools. The growth of facial hair is a trait that is expected to be inherited, while the skill to use stone tools requires learning. However, this study shows that the likelihood of an individual macaque learning how to use stone tools is likely connected to an inherited capacity, or ‘talent’, for using these tools. It could be that the Burmese subspecies have specialized learning capacities for stone tool use or social learning, or they may just be generally smarter, says Assoc Prof Gumert.

Assoc Prof Switzer and Ms Chua, experts on sea level history and past coastal change, were able to construct high quality maps of the current hybridization zone, showing what the researchers interpret as an historical divide between common and Burmese ancestry. In the future, the collaborators are planning to strengthen the biological data with genetic analysis and use geographical history as a tool to reveal possible past animal migration routes in the coastal landscape. For example, outlining the changes in sea levels within Phang Nga bay helps enable determination of whether there was a migration of macaques pre- and post- adoption of tool-use between islands and regions, Ms. Chua explains.

Link to the original article here

Read more about Michael Gumert's research here

Read more about the research by Adam Switzer and Constance Ting Chua at the Coastal Lab web page

Text by Anna Lagerström

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)

7e6fdc03-9018-4d08-9a98-8a21acbc37ba.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=7deaf618_1)