The new economic imperatives of African railways

After decades of neglect railways is starting to get the attention it deserves.

by Rafiq Raji

1. Introduction

African governments have taken a renewed interest in railway infrastructure. While some of the new projects are still motivated by mine-to-port imperatives, others are aimed at moving passengers and freight. Additionally, the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) has added greater impetus for more cross-border railway connections. The African Integrated High-Speed Railway Network is one of a number of initiatives in this regard.[1] While there has always been a desire to link Africa through railway infrastructure, implementation has been slow and, at best, half-hearted. That is primarily because of two reasons. First, for many Africans the railways conjure painful memories of colonialism. It was the railways after all that allowed competing western powers to subjugate Africa and exploit its resources. Second, they are expensive to build, maintain and run. New railways in Kenya and Ethiopia have been operating at a loss, with little chance of paying back loans on time from continually elusive operational profits, for instance. Yet, there is a strong economic imperative behind investing in railway infrastructure. Once constructed, railways can serve as a safe, reliable, and cheap mode of transport. It is also relatively green. Efficient railways keep cars off the roads and reduce traffic, noise pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

Financing is now more readily available for railway projects, as governments, donors and financial institutions prioritise projects that can help meet their sustainability goals. Even so, the other cogent economic considerations for a railway project to become financially sound remain vital. High passenger volumes, market-based fares, flexible terms of concession, significant government investment in the railway projects and the development of a logistics corridor are key requirements to make railways sustainable.

New African railway projects have been dogged by problems. They take too long to complete, run over budget and require constant repair and maintenance once completed. No surprise that most such projects continue to run at a loss and are far from breaking even. Railways have been blamed for contributing to the debt problems of countries like Kenya and Ethiopia that have borrowed primarily from Chinese state-owned financial institutions for their showcase railway projects like the Mombasa-Nairobi and Addis Ababa–Djibouti Standard Gauge Railways (SGRs). But it would be unfair to single out the Chinese. Western banks are beginning to take interest in financing railway projects too. Deutsche Bank and Investec arranged €600m in financing for Ghana’s Western Railway line in June 2021, for instance.[2],[3]

In the article, we first assess the current state of African railways. Thereafter, we highlight ongoing new and proposed railway projects across the continent. Our focus is on the economic case for new and revamped old African railways, how to identify the potential winners and thereafter ensure their commercial viability and sustainability.

2. Economic viability assessment of new African railways

After the end of colonialism African railways entered an era of decay. With road transportation cheaper and offering last-mile connectivity, the incentives to maintain railways diminished. Few new rail tracks were added and the infrastructure that did exist was not maintained properly. With public finances under strain, governments eventually gave out railway concessions to private operators to run. The result was mixed.

In many cases, the new private operators failed to make the concessions profitable. The state was forced to step in to take back control. This time they got a better railway infrastructure in the buyout. In other cases, it was simply left to rot away. While there may be myriad factors behind the failure of private rail projects in Africa, lack of traffic volume is widely attributed to be the principal reason why many of the concessions faltered. Even when concessionaires were free to set their fares, there was simply not enough traffic to breakeven. Requests for renegotiation of contracts often fell on deaf ears, as most African governments simply lacked the will or resources to take on greater financial burdens.

While some governments have continued to run creaky and often outdated rail infrastructure - some nearly a century old - there is now a new motivation for private investors to test the waters again. An ongoing global drive towards climate change mitigation makes African railways quite attractive. Railways are not as carbon-intensive as road transport. Besides, a good rail network can help reduce road congestion and maintenance cost. According to the World Bank, this can add 20-40% in pure financial benefit to the concessionaire.[4]

African railways primarily fall into four different categories - (1) Mineral railways, (2) New railways, (3) Legacy railways and (4) Commuter railways. The transportation of minerals from mines to ports continue to be a major motivation for African railway infrastructure. There are new railways, however, that are not motivated by mining. These are either for moving passengers or freight or both. African railways, some built during the colonial era, continue to be operational across all the categories. Trams have been moving urban commuters in the cities of North Africa for a very long time, for example. More recently, commuter intra-city light rail transport (LRT) and modern inter-city rail have come up in several cities - most recently in Addis Ababa, and for over a decade now in Johannesburg.

As of 2019, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) had a total rail network of 65,760km spread across 32 countries, based on research by the World Bank. 18 of the 32 countries, which gave out railway concessions with 15 to 30 year durations since 1992, had mixed results (see Table 1). No surprise then that investors have not been particularly interested in African railways. Incidentally, those who did invest have lost their money. Anticipating these challenges, concession contracts included mitigants. Governments, which were supposed to make up for actual variances from revenue expectations, for instance, did not come through in many cases.

Railways in Africa are mostly state-run. But for even the ones which are run by private operators, governments are having to take bear more financial burden. That is because most of the non-mineral rail networks barely breakeven. Most of Africa’s legacy railways are in various states of disrepair. According to the World Bank, the key challenges include aging tracks, rail wear, deteriorating earthworks, poor civil works, obsolete signalling and telecommunications equipment and scarcity of spare parts. A huge disincentive to tackling these challenges relate to the lack of commercial viability of most of these rails, as traffic volumes are inadequate to breakeven, even if prices were liberalised. In fact, African rail networks with density over a million traffic units are just about 6 to 8, with others mostly under 500,000 (World Bank, 2020). This lack of scale is a major drawback. European systems average 2-5 million traffic units, for instance (World Bank, 2020).

Railways in Africa are mostly state-run. But for even the ones which are run by private operators, governments are having to take bear more financial burden. That is because most of the non-mineral rail networks barely breakeven. Most of Africa’s legacy railways are in various states of disrepair. According to the World Bank, the key challenges include aging tracks, rail wear, deteriorating earthworks, poor civil works, obsolete signalling and telecommunications equipment and scarcity of spare parts. A huge disincentive to tackling these challenges relate to the lack of commercial viability of most of these rails, as traffic volumes are inadequate to breakeven, even if prices were liberalised. In fact, African rail networks with density over a million traffic units are just about 6 to 8, with others mostly under 500,000 (World Bank, 2020). This lack of scale is a major drawback. European systems average 2-5 million traffic units, for instance (World Bank, 2020).

Data for the most recent year compiled by the World Bank show African railways carried 300m tons (181bn net ton kilometres) of freight and 305 million passengers (12bn passenger kilometres), with mineral lines accounting for more than half of freight traffic. South Africa accounts for the largest rail network in Africa (km). As far as commercial viability goes, freight volume is probably the key determinant. This is because more than 90% of total rail traffic units are owed to freight (World Bank, 2020).

In the African case, the most significant competition to rail is road transport, which offers last-mile connectivity at competitive prices.[5] For African governments that have to manage tight budgets, road infrastructure often takes priority over rail. That is because investment in railways come with higher fixed costs and takes much longer to recover.[6] For long-distance haulage and intra-city commute, however, rail is much more economically viable. But it needs to be modelled well. There are some fundamental economic and financial considerations in determining the choice of gauge for a new railway, for instance. Would there be enough passenger traffic or freight volume to warrant the much more significant upfront investment? If the fixed costs are high then what fares can be fixed to cover those costs? Will the users be able to afford those fares? Would passengers and firms be willing to pay more for a Standard Guage Railway (SGR)?

Although most new African railways have been of the wider standard-gauge (1.435m), instead of the Cape-gauge (1.067m) or meter-gauge (1.000m) that characterise the legacy ones, the size of the gauge itself is not material. Some advanced economies continue to maintain old railways and build new systems based on narrow gauges, for instance.[7] While the wider standard gauge is more suitable for higher speed operations, the assessment must be whether speed is differential to the economic goals of the railway project. There might be no need for a high-speed rail to carry freight, for instance.

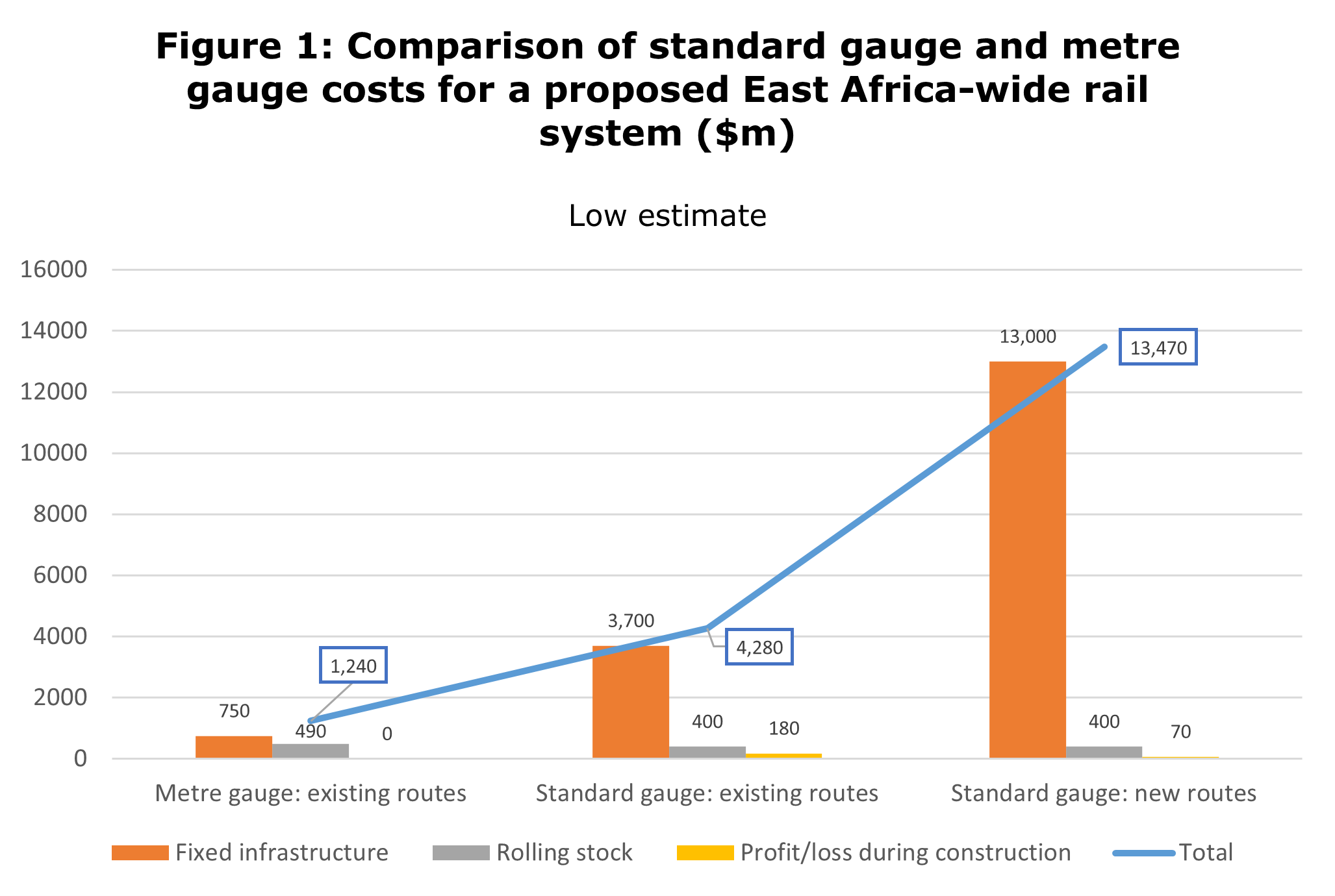

As shown in Figure 1, it costs four to eleven times more to build a new SGR than to repair an old meter-gauge rail. Adopting a narrow gauge for a short-distance rail to match a longer existing network would make more economic sense than a more expensive SGR to replace the entire network, for instance. If the thinner gauge is sufficient for the purpose of the railway, there is no reason to invest in a wider one. For example, the planned Nigerian Port Harcourt-Maiduguri (Eastern Line) SGR project, which was estimated to cost US$11-14bn, has been discarded in favour of the rehabilitation of the existing narrow gauge rail, which could cost as little as US$3.2bn.[8] Although circumstances clearly forced the hand of the Nigerian government towards a cheaper alternative, had the economic imperatives been properly analysed earlier, there would probably have been no need for an SGR in the first place.

Avoiding the error of digging in on an SGR in the face of economic constraints may have been easily achieved in this case of the Eastern line owing to the mixed Nigerian experience with the ongoing US$8.3bn 2,700km Western Lagos-Kano SGR project. Awarded to China Civil Engineering Construction (CCECC) in 2006, the Lagos-Kano SGR has come under severe financial constraint.[10] To manage the funding encumbrances, the Nigerian authorities opted to construct the Western line in phases, securing financing in tandem. Two phases of the Western line, the Lagos-Ibadan and Abuja-Kaduna segments, which are already operational, have suffered myriad operational problems, however.[11]

Avoiding the error of digging in on an SGR in the face of economic constraints may have been easily achieved in this case of the Eastern line owing to the mixed Nigerian experience with the ongoing US$8.3bn 2,700km Western Lagos-Kano SGR project. Awarded to China Civil Engineering Construction (CCECC) in 2006, the Lagos-Kano SGR has come under severe financial constraint.[10] To manage the funding encumbrances, the Nigerian authorities opted to construct the Western line in phases, securing financing in tandem. Two phases of the Western line, the Lagos-Ibadan and Abuja-Kaduna segments, which are already operational, have suffered myriad operational problems, however.[11]

Recently built SGRs in Kenya and Ethiopia by Chinese firms have also been slammed for being expensive and economically unsustainable (see Table 2).[12] In fact, most recently, the Kenyan government has had to exercise the option to take over the running of the Mombasa-Nairobi SGR, which has been operating at a loss since its launch in 2017.[13] Hitherto, Kenya’s aged metre gauge railway system carried no more than a tenth of the cargo coming through the Mombasa sea port.[14] Thus, the decision to build the US$3.8bn 472km Mombasa-Nairobi SGR in May 2014 made sense. But since its opening in May 2017 many issues have come up. The Mombasa-Nairobi line is just the first phase, though. Another, a 369 km line from Nairobi to Naivasha, Kisumu and Malaba is planned.

The US$4.5bn 759km Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway is another interesting case in point. Construction cost overruns ran into half a billion dollars, with payments on the US$3.7bn debt coming due more than a year before train operations started in early 2018.[15] The planned full freight capacity is still a long way off. Scheduling is problematic, power cuts are endemic, and the main Addis Ababa terminal is located far out of town (Voros & Tarrosy, 2018). Security risks from the fast-expanding conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region has now cast an added layer of concern over the viability of the project. This has prompted China to enter into a security arrangement with the Ethiopian police to protect the railway and its other infrastructure investments in Ethiopia.[16]

The US$4.5bn 759km Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway is another interesting case in point. Construction cost overruns ran into half a billion dollars, with payments on the US$3.7bn debt coming due more than a year before train operations started in early 2018.[15] The planned full freight capacity is still a long way off. Scheduling is problematic, power cuts are endemic, and the main Addis Ababa terminal is located far out of town (Voros & Tarrosy, 2018). Security risks from the fast-expanding conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region has now cast an added layer of concern over the viability of the project. This has prompted China to enter into a security arrangement with the Ethiopian police to protect the railway and its other infrastructure investments in Ethiopia.[16]

Suburban rail was previously unknown in much of SSA, except perhaps places such as South Africa and Senegal. North African cities, however, do have a long running love affair with French-style city trams. But modern commuter railway and light rail transit (LRT) systems are now coming up all across SSA (see Table 3). Outside South Africa, however, operations have been hobbled by poor planning and financial constraints. Many such projects therefore remain on the drawing board or face construction delays.

The US$475m Chinese-financed 34.4km Addis-Ababa light railway system, which started operations in 2015, is a much-cited recent example. Hailed at first for its promise of clean and comfortable urban transport, it is now widely seen as an example of what could go wrong. With an average of 110,000 passengers recorded daily (accounting for only 2% of Addis Ababa’s 5 million population) the light railway has fallen short of the primary objective of easing vehicular traffic in Addis Ababa. Overcrowding, power cuts, irregular scheduling, last-mile inadequacies, and limited reach within the city are some of the identified constraints.[18] The financial burden of repaying the loan of the loss-making system is another downside. In a nutshell, the Addis-Ababa LRT has thus far failed to meet its economic and social goals.

The US$475m Chinese-financed 34.4km Addis-Ababa light railway system, which started operations in 2015, is a much-cited recent example. Hailed at first for its promise of clean and comfortable urban transport, it is now widely seen as an example of what could go wrong. With an average of 110,000 passengers recorded daily (accounting for only 2% of Addis Ababa’s 5 million population) the light railway has fallen short of the primary objective of easing vehicular traffic in Addis Ababa. Overcrowding, power cuts, irregular scheduling, last-mile inadequacies, and limited reach within the city are some of the identified constraints.[18] The financial burden of repaying the loan of the loss-making system is another downside. In a nutshell, the Addis-Ababa LRT has thus far failed to meet its economic and social goals.

18 years after, the construction of the seven-line Lagos light rail project by China Civil Engineering Construction (CCECC) remains ongoing.[19] Still, there are renewed expectations that one or two of the Lagos LRT seven lines would become operational in the fourth quarter of 2022.[20],[21] Ground-breaking for the red line of the Lagos rail mass transit (LRMT) project, making two in total of the seven lines currently under construction, was held in April 2021.[22] Financing has been a major constraint. Another is the socio-political costs of constructing the light rail. Property along the route have had to be demolished, with compensation owed previous owners.[23] Managing the politically influential road transportation union is a knotty problem to deal with and so is the turf battle between Lagos state regulatory agencies over jurisdiction.[24]

Africa’s first high-speed railway, the Gauteng Rapid Rail Integrated Network (“Gautrain”) is an 80km commuter line that links South Africa’s big cities, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Ekurhuleni, and the Oliver Tambo international airport. Even before the project got off the drawing board concerns were raised about the project from various quarters. Critics said the opportunity cost of building the Gautrain was too high, and claimed it would only serve the relatively wealthy. [25] Unsurprisingly, South Africa’s Automobile Association (AA) voiced its opposition to planned route extensions of the Gautrain on economic grounds in August 2021, more than a decade after it began operations. According to AA, Gautrain passenger traffic, which has underwhelmed projections thus far, do not support an expansion, arguing for more cost-efficient alternatives with greater mass coverage instead.[26]

3. Social, economic, and environmental approach to railway investments

In making the capital allocation decision on a railway project, cashflow should not be the only consideration. Doing so misses crucial parameters. The social, economic, and environmental (SEE) impacts of the project are equally relevant. Assigning monetary values to the SEE benefits allows for a clearer picture and aligns with the classical discounted cashflow approach more robustly. A monetized SEE analysis makes it easier to point out which of the stakeholders in a railway project or concession are better suited for which undertaking.

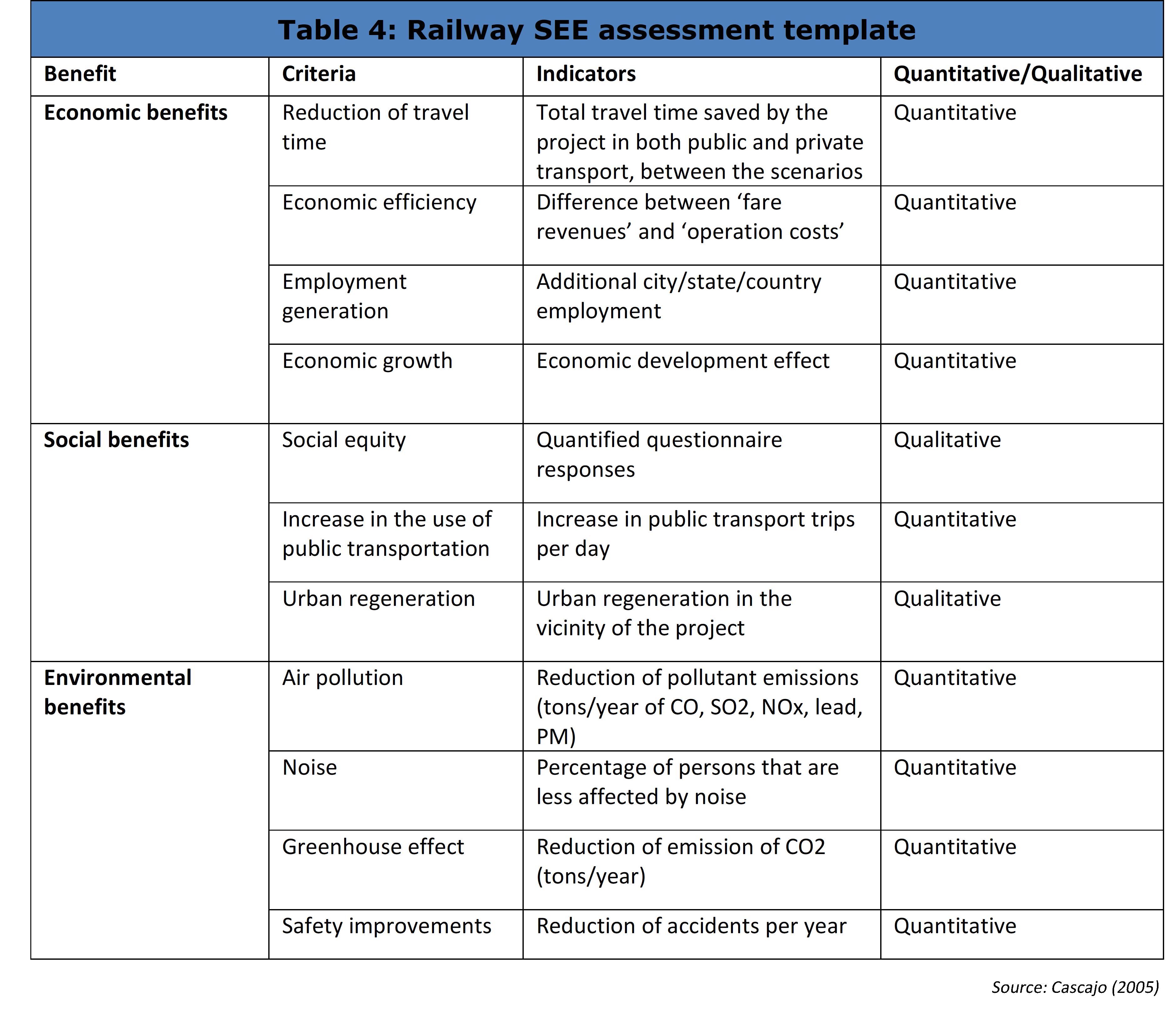

Some previously unattractive railway concessions or projects might actually be found to be economically attractive and in line with an investor’s goals when analysed through the SEE prism. Take the case of a commuter railway, an SEE assessment template for which is shown in Table 4. Commuter railways reduce travel time in most cities and contribute to urban regeneration.[27] They also increase social equity, as the rich and poor use the same mode of transportation. There are less accidents on the road and railways reduce street noise pollution in the cities making them more liveable. So does the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. An efficient urban rail network helps make cities more productive and healthier, which eventually results in economic growth.

As our exposition in the earlier sections show, the low traffic density of most African railways limits their profitability prospects. Apart from mineral railways, there is simply not enough passenger traffic and freight volume for most African railways to be considered attractive on a cashflow basis alone (World Bank, 2020). When analysed through the lens of a monetised SEE impact analysis, however, the non-economic benefits of a railway, become more apparent. It also brings to light why governments should bear a significant portion of the financial burden of a railway concession. But an SEE approach also makes it easier to make a case for more accommodative financing terms with international and development financial institutions (IFIs and DFIs), whose projects often come with social and environmental scrutiny.

Thus, investors must approach the selection of African railway concessions and financing with an SEE mindset. A railway financing request or concession invitation should probably get high marks if such considerations are adopted by the sponsors at the outset. In this event, the project valuation might set out a lesser financial element at the acquisition stage. When this is not the case, the investment decision should be made based on an accurate estimation of the SEE impacts that would ordinarily not be part of the discounted cashflow analysis. Upon agreement with the sponsors on a likely more accommodative valuation thereafter, the concession deal could then be sealed with a mutual understanding of the broader SEE benefits.

In any case, the increasing global environmental, social and governance (ESG) concern means that investors are starting to factor SEE concerns in their investment decisions. It would still be the case, though, that some railway projects would fall below the mark. This should be recognized and necessary accommodation made in the financing agreement should the decision be made to go ahead regardless.

4. Optimization of railway business model and financial structuring

Railway infrastructure, operations and passenger services require different financing approaches and expertise. Assigning all these three aspects of a railway to a concessionaire, typically a railway management firm, has been attributed for failed African railway concessions in the past (AfDB, 2015). Were concessionaires to focus on operations and passenger services, leaving construction, procurement and maintenance to firms with specialist expertise, their cashflows might be positive on a sustained basis, and financing more easily and readily available to them.

The broader socioeconomic imperatives of constructing new African railways, rehabilitating some legacy ones and constructing new LRTs in the continent’s big cities also inform the need for governments to take on the greater financial burden. Even before the environmental advantages of railways gained currency with financiers and other stakeholders, renegotiated concessions bore in mind this realisation. It is simply the case that most of Africa’s railways would barely breakeven, if at all.

For the current momentum to be sustained, however, African governments must make their propositions very attractive for concessionaires and financiers. The likelihood of success in this regard depends on an optimal cost-benefit assessment of each railway project at the outset. As stated earlier, a costlier SGR would not make economic sense if a cheaper narrow-gauge alternative would do. High traffic density mineral railways are almost certainly self-sustaining. Legacy railways, even those with relatively ample freight volumes, are not able to do similarly.

To keep costs low, increase the chances of breaking even and maintain a positive cashflow, the upfront fixed costs of a railway project can be reduced first by making the right choice on the selection of the gauge and then deciding whether to build a new rail line or rehabilitate an old one. Once in operation, periodic maintenance could be done at longer intervals, track renewal only on occasion and replenishment of rolling stock only if necessary. The long-term potential of a railway concession must also be writ large. It would be all too obvious the likely eventual success of a railway system that connects to a port, airport, and key road interchanges as part of a wider logistics chain, for instance.

To keep costs low, increase the chances of breaking even and maintain a positive cashflow, the upfront fixed costs of a railway project can be reduced first by making the right choice on the selection of the gauge and then deciding whether to build a new rail line or rehabilitate an old one. Once in operation, periodic maintenance could be done at longer intervals, track renewal only on occasion and replenishment of rolling stock only if necessary. The long-term potential of a railway concession must also be writ large. It would be all too obvious the likely eventual success of a railway system that connects to a port, airport, and key road interchanges as part of a wider logistics chain, for instance.

Financiers should certainly focus on high volume passenger African markets and freight-focused railways that form part of a logistics chain.[28] But how many of these are available for investment? As shown in Table 5, only about a quarter of SSA railways have a traffic density of more than 3m net tons. In fact, the lesser the traffic density the greater the likelihood that the state will be required to carry the higher or all the financial burden, which is already the case for about 75 percent of all SSA railways, according to the World Bank.

Financiers should certainly focus on high volume passenger African markets and freight-focused railways that form part of a logistics chain.[28] But how many of these are available for investment? As shown in Table 5, only about a quarter of SSA railways have a traffic density of more than 3m net tons. In fact, the lesser the traffic density the greater the likelihood that the state will be required to carry the higher or all the financial burden, which is already the case for about 75 percent of all SSA railways, according to the World Bank.

As shown in Table 6, the investment or financing decision should be dependent on whether the business model is optimal and fit-for-purpose in regard of the peculiarities of the subject African market. A concessionaire focused on just passenger services can take on or off-balance sheet financing that is separate from the sovereign owner of the railway. A government could also finance the construction of new railways or the rehabilitation of legacy lines, current and periodic maintenance of assets, as well as the procurement of rolling stock, using an adaptable mix of on- and off-balance sheet financing that leverages on its sovereign credit rating without weighing on the concessionaire’s balance sheet.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

As the world transitions towards greener energy sources and ramps up climate action, the payoff for transportation modes like railway is more than just financial and should be measured as such. An African railway project that cannot break even need not be rejected outrightly. Its returns should be seen through a more comprehensive SEE lens. Nonetheless, the viability and sustainability of a railway concession or system are greatly dependent on key economic imperatives, which SEE considerations can complement. Anticipated passenger and/or cargo volumes should be large enough to justify investments in rail projects. These must not be prestige projects. Fares must be above marginal costs. Concessions must be flexible and allow for periodic renegotiations. And finally, governments must be willing to take on a greater financial burden, especially with respect to fixed costs.

An efficient rail network remains a better alternative for long-distance haulage. Commuter railways are certainly greener than road alternatives but its design must take into cognisance some of the advantages of road transportation like last-mile connectivity, greater flexibility and frequency that are not easily replicable by LRTs. The case of the Addis Ababa LRT, as shown in this article, is a cautionary tale of a project gone wrong. What should have been a panacea to traffic congestion on the roads has instead become a drag for the exchequer. After an initial flurry of excitement, most city commuters have reverted to using the buses.

To realise its full economic potential, African railways must be backed by strong governance, a sustainable financing mechanism and creative market development, as the World Bank argues. Optimal economic decision-making should also underpin the railway projects at the outset, before costs become entrenched and are not easily reversible. How the various activities, from passenger services, infrastructure and maintenance and rolling stock are modelled, matter a great deal too.

How much of the fixed cost burden is being carried by the sponsor government? Is ticket pricing market-based? Is traffic density high enough? Would a narrow-gauge rail suffice? Is there a robust economic justification for a new SGR? These are some of the key questions to ask before deciding on a railway concession or financing. In our exposition of the African case thus far, we show how the answers to these questions might not be encouraging to a prospective investor, financier or concessionaire initially. But when analysed from a wider economic value perspective, especially with respect to their potential social, economic, and environmental impacts, there might be more than a few attractive prospects.

For current and prospective investors, financiers, and concessionaires in new, legacy and commuter African railways, we recommend the following:

- Monetise SEE benefits of railways in investment decision

Monetising the SEE benefits of a railway allows for a more robust approach in deciding whether to finance a project or not. Some previously unattractive railway concessions or projects might be found to be economically attractive in the aftermath. Considering the low traffic density of most African railways, an SEE impact analysis could make a strong case for governments to step in to cover the fixed costs, leaving the concessionaire to focus on passenger services and freight operations. More accommodative financing terms from IFIs and DFIs are also likely with an SEE approach.

- Adopt optimal railway business model and financial structuring approach

Railway infrastructure, operations and passenger services require different financing approaches and expertise. Interested investors should hinge their capital allocation decisions on whether the business model of the railway concession or project is optimal with respect to the African market being considered. In most, a prospective concessionaire should not accept terms insisting that it build new rail infrastructure, for instance. A financier should probably shun funding requests by a non-sovereign entity for railway infrastructure, maintenance, and the procurement of rolling stock. A concessionaire focused on just passenger and freight services is best for most African railways. Consequently, the concessionaire is likely to have positive cashflows on a sustained basis since the cost-heavy fixed components are borne by the sovereign. Financiers who optimize as such are also likely to earn positive returns.

References

[1] African Union Development Agency & NEPAD (2020, July 7). Update on the African Integrated High-Speed Railway Network by AUDA-NEPAD [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.nepad.org/overview/update-african-integrated-high-speed-railway-network-auda-nepad

[2] Ojekunle, A. (2021, July 12). Amaechi: FG still discussing with Standard Chartered over railway project loan. The Cable. Retrieved from https://www.thecable.ng/amaechi-fg-still-discussing-with-standard-chartered-over-railway-project-loan

[3] Deutsche Bank, Investec arrange EUR 600 mln financing to construct railway line in Ghana (2021, June 29). Markets Insider. Retrieved from https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/deutsche-bank-investec-arrange-eur-600-mln-financing-to-construct-railway-line-in-ghana-1030562043

[4] World Bank (2020). Modern railway services in Africa: Building traffic – building value. Washington DC: The World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34576/Modern-Railway-Services-in-Africa-Building-Traffic-Building-Value.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] Bouraima, M.B., Qiu, Y., Yusupov, B. and Ndjegwes, C.M. (2020). A study on the development strategy of the railway transportation system in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) based on the SWOT/AHP technique. Scientific African, 8. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468227620301265

[6] World Bank (2017). Railway reform: Toolkit for improving rail sector performance. Washington DC: World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30734/69256-REVISED-ENGLISH-PUBLIC-RR-Toolkit-EN-New-report-date-2017-12-27.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[7] Saito, A. (2002). Why did Japan choose the 3’6” narrow gauge? Japan Railway & Transport Review, 31, pp. 33-38. Retrieved from https://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr31/f33_sai.html

[8] Falaju, J. (2021, March 15). Why FG opted for narrow gauge on Eastern rail line, by Amaechi. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/news/why-fg-opted-for-narrow-gauge-on-eastern-rail-line-by-amaechi/

[9] Taylor, I. (2020). Kenya’s new lunatic express: The standard gauge railway. African Studies Quarterly, 19 (3-4), pp. 29-52. Retrieved from https://asq.africa.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/168/V19i3-4a3.pdf

[10] Ayemba, D. (2021, August 14). Lagos-Kano SGR project timeline and what you need to know. Construction Review Online. Retrieved from https://constructionreviewonline.com/project-timelines/lagos-kano-sgr-project-timeline-and-what-you-need-to-know/

[11] Editorial Board (2021, July 11). The embarassing train breakdowns. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/opinion/the-embarrassing-train-breakdowns/

[12] Chen, Y. (2019, June 4). Ethiopia and Kenya are struggling to manage debt for their Chinese-built railways. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/1634659/ethiopia-kenya-struggle-with-chinese-debt-over-sgr-railways/

[13] Kenya to take over Chinese-operated rail line five years early (2021, March 15). Global Construction Review. Retrieved from https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/kenya-take-over-chinese-operated-rail-line-five-ye/

[14]Irandu, E.M. & Owilla, H.H. (2020). The economic implications of Belt and Road Initiative in the development of railway transport infrastructure in Africa: The case of the standard gauge railway in Kenya. The African Review, 47 (2020), pp. 1-24. Retrieved from https://brill.com/downloadpdf/journals/tare/47/2/article-p457_9.xml

[15] Tarrosy, I. & Voros, Z. (2018, February 22). China and Ethiopia, Part 2: The Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway. Academia. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/china-and-ethiopia-part-2-the-addis-ababa-djibouti-railway/

[16] China, Ethiopia ink accord on establishing security safeguarding mechanism for major projects under BRI (2021, March 6). Xinhua. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-03/07/c_139792150.htm

[17] Africa: Upcoming urban rail projects (2016, November 1). Global Mass Transit Report. Retrieved from https://www.globalmasstransit.net/archive.php?id=23846

[18] Voros, Z. & Tarrosy, I. (2018, February 13). China and Ethiopia, Part I: The light railway system. Academia. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/china-and-ethiopia-part-1-the-light-railway-system/

[19] Olawoyin, O. (2020, December 18). Lagos light rail: 17 years after, failed promises, rot, neglect trail project. Premium Times. Retrieved from https://www.premiumtimesng.com/investigationspecial-reports/431862-lagos-light-rail-17-years-after-failed-promises-rot-neglect-trail-project.html

[20] Editorial Board (2021, May 23). The return of Lagos rail project. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/opinion/the-return-of-lagos-rail-project/

[21] Olisah, C. (2021, February 25). Lagos says blue, red rail lines will be ready by December 2022. Nairametrics. Retrieved from https://nairametrics.com/2021/02/25/lagos-says-blue-red-rail-lines-will-be-ready-by-december-2022/

[22] Nigeria’s economic hub starts construction of new light rail to improve connectivity (2021, April 16). Xinhua. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/africa/2021-04/16/c_139884208.htm

[23] Alade, B. (2021, April 30). Lagos begins demolition for light rail project. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/saturday-magazine/travel-a-tourism/lagos-begins-demolition-for-light-rail-project/

[24] Lagos State House of Assembly. (2016, July 27). NIWA hinders Lagos light rail project – Mojeed [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.lagoshouseofassembly.gov.ng/niwa-hinders-lagos-light-rail-project-mojeed/

[25] Thomas, D.P. (2013). The Gautrain project in South Africa: a cautionary tale. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 31(1), pp. 77-94. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Thomas-43/publication/263372046_The_Gautrain_project_in_South_Africa_a_cautionary_tale/links/5d5fdbeea6fdccc32cc9ea49/The-Gautrain-project-in-South-Africa-a-cautionary-tale.pdf

[26] New Gautrain route must be rejected says AA – here’s what should be done instead (2021, August 13). BusinessTech. Retrieved from https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/512908/new-gautrain-route-must-be-rejected-says-aa-heres-what-should-be-done-instead/

[27] Cascajo, R. (2005, May 11-13). Assessment of economic, social and environmental effects of rail urban projects [Paper presentation]. Young Researchers Seminar 2005, The Hague, The Netherlands. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rocio-Cascajo/publication/237576161_ASSESSMENT_OF_ECONOMIC_SOCIAL_AND_ENVIRONMENTAL_EFFECTS_OF_RAIL_URBAN_PROJECTS/links/0c960529700b75b9fd000000/ASSESSMENT-OF-ECONOMIC-SOCIAL-AND-ENVIRONMENTAL-EFFECTS-OF-RAIL-URBAN-PROJECTS.pdf

[28] African Development Bank (2015). Railway infrastructure in Africa: Financing policy options. Abidjan: AfDB. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Events/ATFforum/Rail_Infrastructure_in_Africa_-_Financing_Policy_Options_-_AfDB.pdf

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)