Egypt emerges as a top FDI destination

Time for investors to take fresh look at a market that lies at the cross-roads of international trade

By Hebatallah Ghoneim

Because of Egypt’s strategic location and the large size of its domestic market, it is a country capable of attracting substantial foreign direct investment (FDI) (Tarek & Ghoneim, 2018[1]). The Government of Egypt (GOE) has carried out several economic reforms to create an environment conducive to FDI; this includes the reactivation of interbank foreign exchange, the enactment of a new investment law in 2017, and a new company’s law, bankruptcy law and customs law in 2020. Mega projects, such as the new administrative capital and the development of the Suez Canal area, have also generated enthusiasm. The GOE is engaged in more than 100 bilateral investment treaties and is also working on a stable fiscal and monetary policy that will contribute to creating a healthy investment environment (2020 Investment Climate Statement [2]).

This report provides a descriptive overview of FDI inflows in Egypt, explores the main determinates and major achievements, and highlights the challenges of attracting FDI in Egypt. This paper also outlines potential areas for investment and serves as a guide for policymakers.

This paper addresses the following questions:

1. What is the trend of FDI growth in Egypt?

2. What makes Egypt an attractive FDI destination?

3. To what extent have economic reforms succeeded in improving the investment climate in Egypt?

4. Why should Asian investors pay attention to Egypt?

1. Impact of Economic Reform Program on FDI

Since the launch of the Economic Reform and Structural Adjustment (ERSAP) program in the early 1990s, the GOE has used FDI as a primary means of increasing capital and accelerating growth. To attract foreign investors, in the 1990s, the GOE ratified laws that limited foreign ownership, waived custom duties and established free zones (Hanafy, 2015[3]). Then, during the early 2000s, the GOE worked on creating a better investment environment by empowering the General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI) to act as a ‘one stop shop’ for investors. This single-window facility helped facilitate FDI inflows, which came close to hitting US$12 billion in 2007 and accounted for 9% of Egypt’s GDP, compared to only 0.5% in 2001 (Figure 1).

FDI inflows remained healthy until 2011, when the Arab Spring revolution abruptly reversed the positive trend. Then, it was not until 2014 that the situation started to improve. After the introduction of economic reform packages under President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, FDI inflows exceeded US$6 billion in 2015. With the Egyptian pound stabilising after a 15.9% drop in 2013, foreign investors’ confidence began to return. The economic reforms not only introduced a flexible exchange rate regime but also set fiscal consolidation as a priority. To balance the budget, a Value Added Tax (VAT) was introduced and subsidies (except for low-income households) were removed (Helmy et al., 2019[5]).

In 2017, a more business-friendly investment law was ratified. This law guarantees the equitable treatment of domestic and foreign firms, and an investor service centre has been established to facilitate the issuance of licenses. The new law also gives foreign investors the ‘right’ to a temporary residence during the project, guarantees their freedom to repatriate profits (after tax), and protects them against state seizure of assets and/or capital (Alex Bank, 2017[6]; Hashish et al[7]., 2018-2019).

The GOE has also granted tax exemptions for projects that deliver ‘inclusive sustainable growth’, such as projects that include labour intensive production, small and medium enterprises (SME), renewable energy, automobile manufacturing, exports, pharmaceuticals, tourism, and power (AlexBank, 2017; Mbengue, 2019[8]). The investment law allows a tax deduction for investments in corporate social responsibility (CSR), research and development (R&D), environmental protection, health care and cultural enrichment (AlexBank, 2017; Mbengue, 2019). In principle, the GOE is not just targeting the quantum of FDI inflows but the quality—one that is in alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In the last 20 years, Egypt has been the top recipient of FDI in Africa. Between 2001 and 2019, Egypt’s net FDI inflows topped the continent and ranked third in comparison with other Arab countries (Figure 3). Even in 2021, Egypt continues to have the highest FDI rates in Africa - this despite the sharp decrease in FDI inflows experienced by the continent following the pandemic (UNCTAD Database[9]). Total FDI inflows in Egypt amounted to US$5.9 billion in 2020, which is more than half the inflows recorded for North Africa that year (UNCTAD database, 2021). According to the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE[10]), more than half of FDI inflows into Egypt between 2019 and 2020 were either for new businesses or for raising capital for the expansion of existing operations.

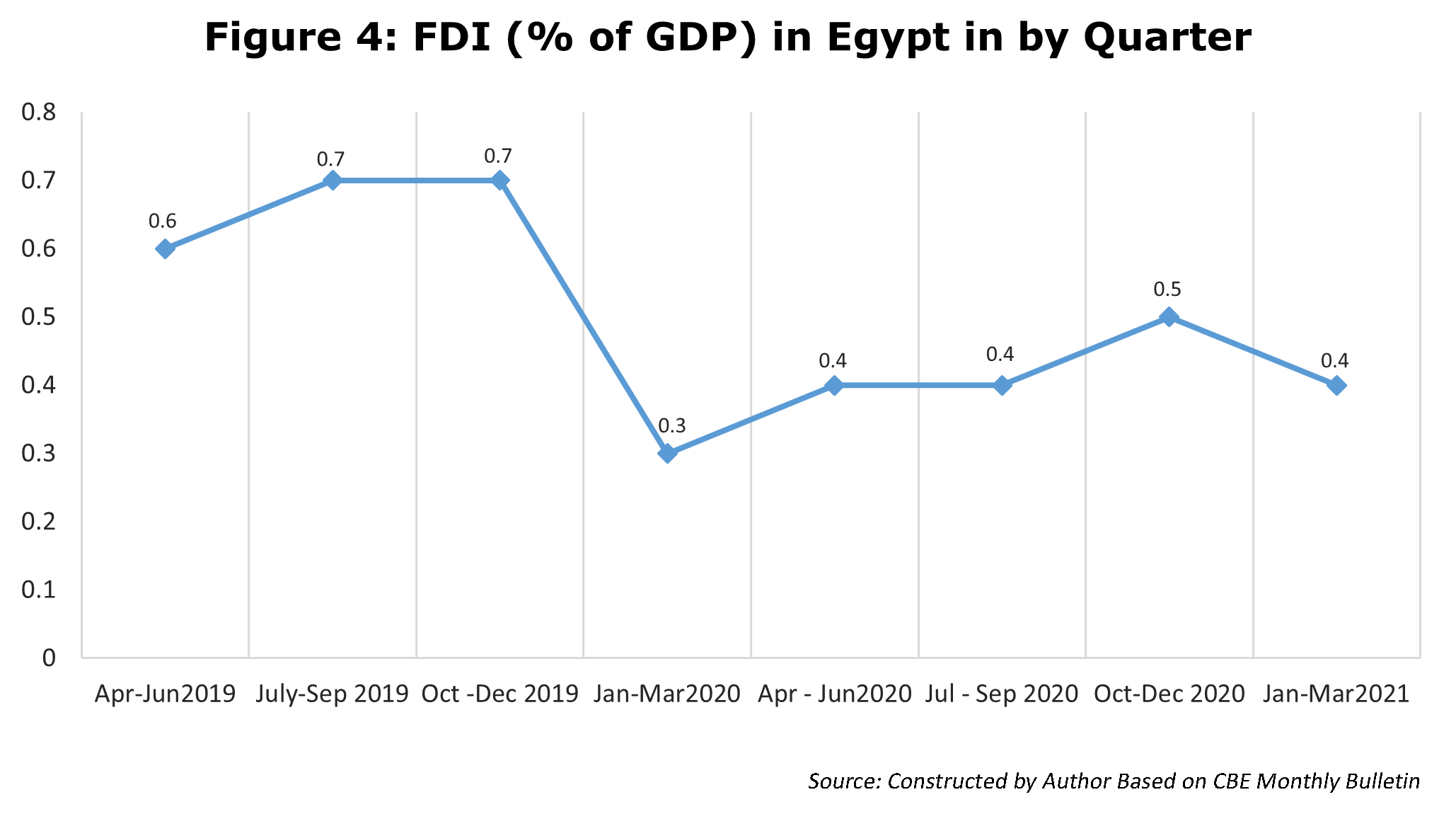

Based on data provided by CBE, there was a sharp decrease in FDI inflows during the first quarter of 2020, followed by a noticeable increase in the last quarter of the same year (Figure 4). UNCTAD (2021[11]) attributed this increase to the Saudi–Egyptian investment agreement that secured investments in different sectors, including tourism, health, infrastructure, financial services, education, food, and telecom. Also, new investments in the offshore gas fields at Zohr, Baltim Southwest, Kattameya and Kamose-North have contributed to an uptick in foreign investments.

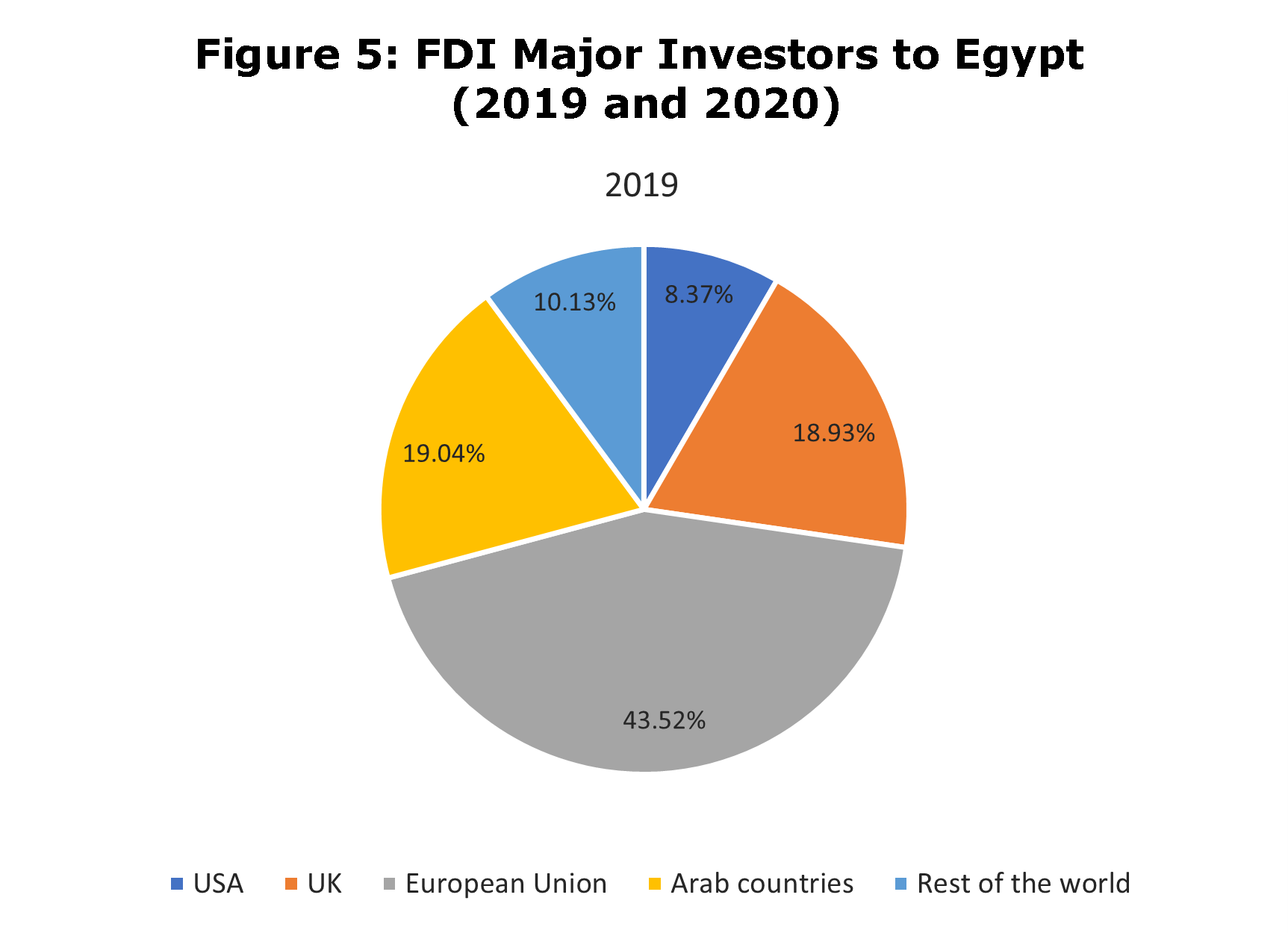

Nearly 90% of the FDI in Egypt originates from the European Union, Arab states, the UK, and the USA (Figure 5). In 2013, Egypt and the EU signed the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) agreement, which aims to improve market access and the investment climate. This deal extended a 2004 agreement that created the free trade area between Egypt and the EU, adding new trade in services, government procurement, competition, intellectual property rights and investment protection. This is one reason why the EU remains the top investor in Egypt. In December 2020, Egypt signed a bilateral trade agreement with the UK (known as the ‘UK and Egypt Association Agreement’) that was expected to expand both trade and investment opportunities for Egypt (UK and Egypt sign Association Agreement, 2020[12]). Until now, companies across industries have been operating in Egypt, including BP and Shell in the petroleum sector, Unilever in the retail sector, AstraZeneca and GSK in the pharmaceutical sector, and Vodafone Egypt in the communications sector. However, this new agreement seeks more cooperation attracting FDI in the education and renewable sectors.

In general, British investments in Egypt have been relatively diversified, while Italy has been heavily involved in the development of the gas fields. The UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are the leading Arab investors in Egypt, but their interest has largely been in the real estate sector.

2. What makes Egypt an attractive FDI destination?

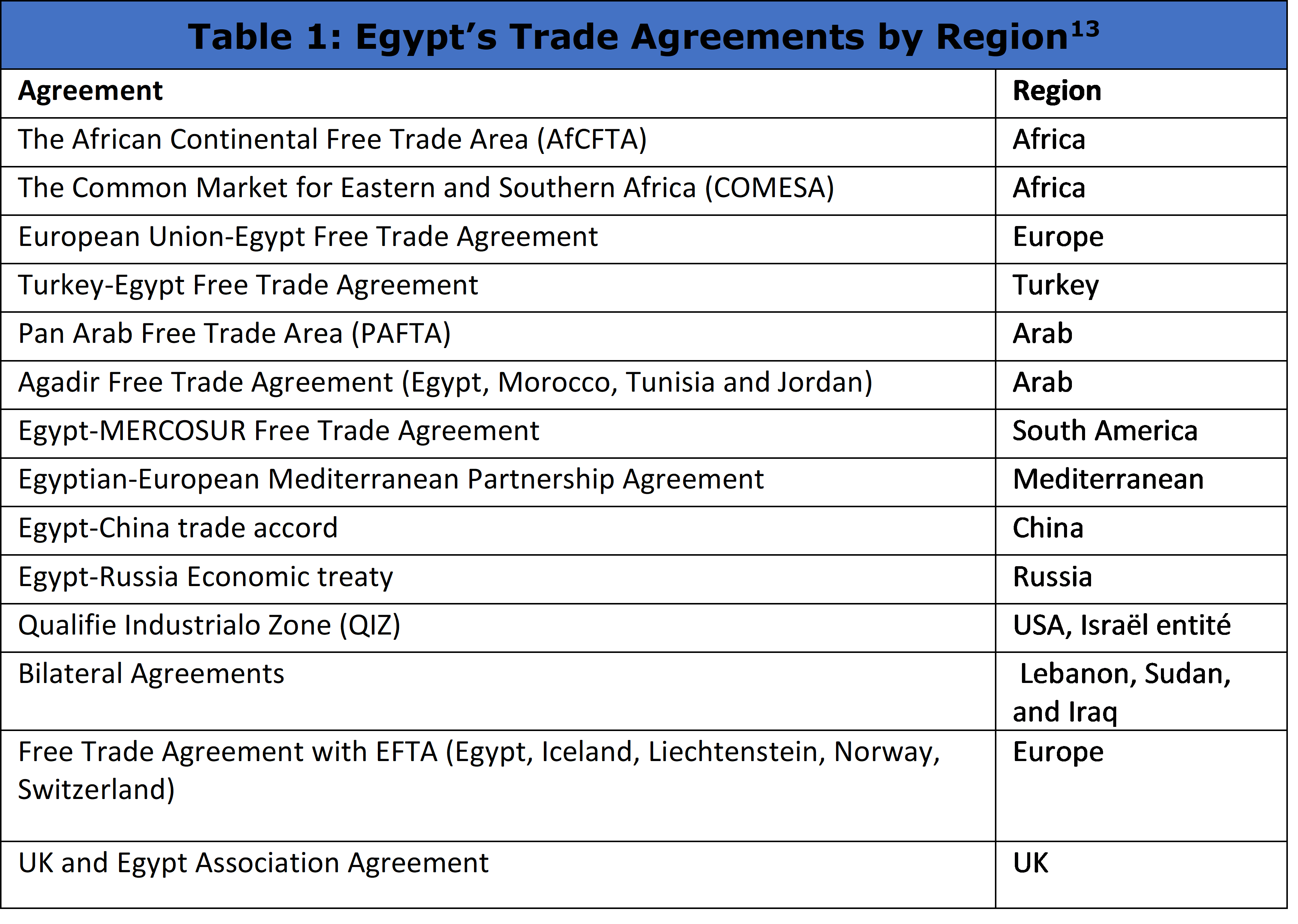

With a population of more than 100 million, the size of Egypt’s domestic market is already large enough to attract FDI investors. However, preferential access to Europe and free trade agreements with a number of other markets makes it an attractive for manufacturing (see Table 1).

Additionally, a series of macroeconomic and structural reforms have set the country on a healthy growth trajectory. Even during the height of the pandemic, Egypt grew at 3.56%. In its latest review of IMF economic reform it is predicted that Egypt’s economic growth will reach 2.8% in FY 2020/21 and rebound strongly to 5.2% in FY 2021/22. Nevertheless, the IMF review stressed the importance of further public expenditure cuts, the control of public debt, and the promotion of inclusive and sustainable private sector-led growth to create durable jobs (IMF Country Focus, 2021[14]).

In 2016, CBE switched from a managed exchange rate to a free-floating exchange rate, letting the Egyptian pound slide in value. It fell from 8.87 to a dollar (US) to 14.3 to a dollar (US) in a matter of two weeks. But the depreciation of the Egyptian pound also made exports much more competitive – thanks to the comparative cost advantage. According to Fadl and Ghoneim (2020[15]), a depreciating foreign currency has always been one of the determinants of FDI inflow. Nevertheless, over the last three years, the exchange rate has settled and there is much less volatility in the currency market. This has brought about economic stability economy significantly reduced the risk of currency devaluation.

In 2016, CBE switched from a managed exchange rate to a free-floating exchange rate, letting the Egyptian pound slide in value. It fell from 8.87 to a dollar (US) to 14.3 to a dollar (US) in a matter of two weeks. But the depreciation of the Egyptian pound also made exports much more competitive – thanks to the comparative cost advantage. According to Fadl and Ghoneim (2020[15]), a depreciating foreign currency has always been one of the determinants of FDI inflow. Nevertheless, over the last three years, the exchange rate has settled and there is much less volatility in the currency market. This has brought about economic stability economy significantly reduced the risk of currency devaluation.

Its well-qualified but relatively low-cost workforce makes Egypt attractive to the manufacturing and service sector. Egypt is also rich in natural resources, such as hydrocarbons, iron ore, phosphate, manganese, limestone, gypsum, talc, asbestos, lead and zinc. These factors should make Egypt attractive to foreign investors.

For years, businesses struggled to cope with frequent power cuts, but these have become a thing of the past. Thanks to concert investments made in power generation and regulatory reforms, Egypt now produces surplus electricity at a rate of 25%[16] . The GOE has also restructured electricity tariffs and issued a five-year plan (commencing in 2017) to phase out subsidies, which is an attempt to provide electricity at the cost of production and save approximately US$1.14m in electricity subsidy bill (IRENA, 2018[17]). The ministry of electricity has also switched to levying progressive tariff based on income level in a bid to support low-income consumers and create an incentive for saving energy. The state now allows the private sector to bid on contracts to handle the maintenance and management of power plants. Power substations, such as those in New Ismailiyah, Eastern Sohag and October city, and the construction of three mega stations in Beni Sweif (Upper Egypt), Borlus (beside Port Said) and New Capital city have been replaced resulted in the expansion of the capacity to produce 14000 megawatts (MW)[28] of more electricity.

One of the 2030 agenda is to generate half of the country’s electricity through renewable sources. Because Egypt is rich in hydro, wind, solar and biomass a great deal of attention is being given to investments in renewable energy. The GOE is working on expanding wind and solar farms, which represented slightly less than 5% of total electricity generated (2018). The largest wind farms are those located at Zaafarana and the Gulf of El-Zayt, which have a capacity of about 750 MW.

Investments in major road projects have eased traffic congestion and lowered the cost of logistics in Egypt. Most of these new roads are centred around the capital, such as Cairo-Ain Shkouna Road, Cairo-Alexandria desert road, Road Al-Farag Road, Suez-New Capital Road, 30 June Axis road (which links Cairo with Canal cities), Shoubra-Benha Road (which reduces traffic on the path to Cairo), Alexandria Road, Al-Fouka Road, and Wadi El-Natroun Road (which links Cairo with the North Coast). However, roads have also been constructed to facilitate transactions in other governorates (i.e., provinces), such as Dahshur-Wahat-Fayoum Road and Farafra-Dairut Road (which try to make the Oasis in West Egypt Desert less marginalized), Sohag-Red Sea Road (which is part of the effort to develop Upper Egypt), and El-Galala Road (which makes it easier to reach coastal cities along the Red Sea).

For decades, FDI in Egypt flowed primarily into the oil and gas sector and Cairo benefited most from these investments. Even now, five out of the 26 Egyptian governorates take up 90% of the FDI (Hanafy, 2015; OECD, 2020[19]). The GOE is trying to channel FDI into other regions (targeted investment represented in Table 2 based on GAFI website) but has only been partially successful in achieving this thus far.

Construction and real estate accounted for 11.1% of total FDI flows received by Egypt in 2018/19 in comparison with 3.6% in 2013/14. During the same period, the proportion of FDI into the service sector (such as transport, logistics and finance) also increased from 5% to 17.6% (OECD, 2020). Nonetheless, oil and gas remains the sector that receives most of the FDI - although its share in the total FDI basket is reducing. According to the CBE 2019-2020 economic review, FDI inflow in oil and gas came down from 63.4% in 2018/2019 to 55.4% in 2019/2020.

The GOE is trying hard to maintain its status as a premier investment hub in North Africa. It has succeeded in maintaining macroeconomic stability, which has improved the environment for doing business, and has launched several projects aimed at diversifying the economy.

The GOE is trying hard to maintain its status as a premier investment hub in North Africa. It has succeeded in maintaining macroeconomic stability, which has improved the environment for doing business, and has launched several projects aimed at diversifying the economy.

For example, one of these projects targets the agriculture sector. The project, grandly titled - ‘Land Reclamation of 1.5 million Acres’, aims to increase land available for agricultural use by 20%. The government has targeted Tosheka and West Minyah in Upper Egypt, Farafrah Qasis in the New Valley governorate (which is one of the frontier governorates located in the West Desert), and El Magraa in the West Delta for this project. It is hoped the land reclamation project will not only enhance Egypt’s food security but will also help accelerate the economic development of long neglected rural communities. Food exports, which account for nearly 18% of the total exports in Egypt are also expected to grow. The 1.5 million Acres project is the first stage of a plan targeting 4 million acres that would provide raw materials to important industries, such as textile manufacturing, leather production and food processing (Arab Republic of Egypt General Authority for Investment and Free Zones website).[21]

Another example of a project aimed at diversifying the economy is the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SEZone), which is part of government policy expanding investment in Suez Canal governorates. The GOE has paid full attention to this strategic area to expand employment opportunities for the North Sinai, South Sinai, and East Delta governates as well as to benefit from the natural resources accessible in these regions. The SEZone includes four different industrial zones and plans for the development of six different airports in the area. The SEZone is expected to act as a logistics hub and industrial processing centre within the region, benefiting from the Suez Canal’s potential to act as a gateway between East and West. The SEZone authority acts as a ‘one stop shop’ for investors wanting to register and start business in Egypt. It is empowered to issue licences, work permits and can even act as an intermediary to settle dispute. Incentives such as waiving of customs duties for imported capital equipment and raw materials has also been extended to foreign investors as well as sales and indirect tax exemption.[22]

The Golden Triangle, which is located between Qena, Safaga and Al Qusair, is another economic zone that is expected to attract FDI. This region is rich both in terms of the available mining resources and in terms of its highly touristic coast, which is located between the Nile and the Red Sea. Since 2017, the GOE has worked on developing infrastructure in this area by creating essential roads, water springs and electricity, and a special authority unit responsible for managing the project’s development. The area is expected to host different industries (e.g. cement, glass, silicon, chemicals and computer chips) that will benefit from the rich mining resources in the Golden Triangle. Additionally, because this area includes the ancient pilgrimage route to Mecca, it is especially appealing as a tourist destination. The Golden Triangle project will also serve as a trade road linking Upper Egypt with the Safaga sea port. Moreover, the area will benefit greatly from the solar energy project located in Safaga, which is one of the major renewable energy projects included in Egypt Vision 2030 (Arab Republic of Egypt General Authority for Investment and Free Zones website).

Foreign investors have been participating in real estate projects such as the New Capital City, New Alalamin and Galala. Now opportunities for investors have opened in the renewable energy sector – such as the solar, wind, and more controversially, nuclear energy plants in Dabaa. Projects have also been launched in the manufacturing sector, such as the leather-making centre in Al-Robbiki City and furniture-making projects in Damietta City (based on GAFI website).

3. Asian Investment in Egypt

Egypt is a unique Afro-Asian country, where Sinai is considered the bridge that links Egypt with the Asian continent. Suez Canal has long been a critical thoroughfare for trade between Asia and Europe. Although the Gulf states have been dominant foreign investors in Egypt (see Figure 9) the GOE is wooing investors from other parts of Asia. FDI inflows from Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar accounts for 23.5% of all FDI received in 2020. Inflows from the Gulf increased in 2020 despite the pandemic. This could be the result of dialling down of political tensions between Qatar and Egypt relations. Of the top five Gulf countries investing in Egypt, the UAE is in a league of its own – accounting for half of the total FDI inflows received from these five countries. Investments from the UAE include large-scale renewable projects (Al-Nowais Group in Upper Egypt and Suez Gulf), downstream oil and gas retail, construction and real estate development (Majiid Alfatuim and Emaar). UAE’s Global Education Management Systems (GEMS) has also acquired a number of international and language schools in Cairo. Similar acquisitions have also been made in the health sector.

China turned into a major investor after Egypt signed a comprehensive ‘strategic’ partnership in 2014 Despite the effects of the pandemic, China invested more than US$300m in Egypt in 2020 and approximately US$159m in the first quarter of 2021 (CBE Statistics Bulletin). Between 2015/16 and 2019/20, FDI inflows from China increased by approximately 68% (see Figure 10). The most notable Chinese investment is the Suez Economic & Trade Cooperation Zone (SETC-ZONE) at Ain-Sokhna. It has attracted a number of Chinese manufacturing units providing them access to the European and North African market. The SETC-ZONE includes multiple sectors, including textiles and clothing, petroleum equipment, fiberglass, and high- and low-voltage electrical equipment (Scott, 2013[23]). This is in addition to increased Chinese investments in building the new capital infrastructure (El-Tawil, 2018[24]).

Investments from South Korea and Singapore exceeded US$50bn in the first quarter of 2021 (see Figure 11) reversing the trend seen in the two years prior when investors from the two countries pulled out their relatively modest exposure. It shows renewed interest in Egypt and a fresh vote of confidence. South Korean giants Samsung and LG dominate the electronics market in the country. It has recently also been announced that a South Korean company will start manufacturing tablets in Egypt. Major investment in agriculture, communication, construction, services, clean energy, maritime transportation, infrastructure and sea water desalination is also expected from South Korea (MTS, 2021).[25]

Singapore has taken steps towards expanding its footprint in Egypt. Its firms are venturing in logistics, retail, and the financial sector. One of the biggest projects is a US$10m logistics hub in the SEZone. It is expected to double in size (Cheong, 2020[26]). In 2018 an agreement between Egypt and Singapore to boost investments in fintech. The result was the emergence of ten new fintech start-ups in Egypt. Yet, these are still early days for Singapore firms in Egypt. There remains a lot more room to grow.

4. Summary

Recently, Egypt has succeeded in growing its economy and improving its position in terms of doing business (ranked 114 in 2020 in comparison to 131 in 2016). The mega projects and free zones the GOE have recently established have succeeded in setting Egypt on the top of the continent as a recipient country for FDI. However, many questions have been raised about the major investment in the construction sector, which can lead to inflated prices, expanded real state supply, and challenges relating to further demand in the construction sector. Also, the country’s ability to become more digital, especially under the ongoing threats related to the pandemic and the need for social distancing, raises major concerns. For further economic expansion, major improvements should be made within the internet connection sector, specifically, and the telecommunication sector more generally.

References

[1] Tarek, S. & Ghoneim, H. (2018) Have FDI enhanced growth in Egypt? GUC Working Paper no 49- September 2018. Retrieved from: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/gucwpaper/49.htm

[2] 2020 Investment Climate Statements: Egypt. U.S. Department of State Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-investment-climate-statements/egypt/

[3] Hanafy, S. (2015). Patterns of foreign direct investment in Egypt: Descriptive insights from a novel panel dataset at the governorate level (No. 12-2015). MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics.

[4] WorldBank Databank. World Development Indicators. Retrieved from: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

[5] Helmy, I., Ghoneim, H., Siddig, K., & Richter, C. (2019). Reaping the harvest of economic reforms: The case of social safety nets in Egypt. Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES) Working Papers, (200).

[6] Alex Bank (2017). Egypt’s New Investment Law: July 2017. Alex Bank. Retrieved from: https://www.alexbank.com/document/documents/ALEX/Retail/Research/Flash-Note/AR/New-Investment-Law_Jul17.pdf

[7] Hashish, M., Taha, W., Kaplan, A., Liberman, M., Cooper, D., Pfeiffer, D., Saab, O., EL-Khalil, H., Blount, K., Malkawi, B. and Ridgwa, D.A. (2018-2019). Egypt. In The Year In Review: An Annual Publication of The ABA/Section of International Law (pp. 655-657). American Bar. Retrieved from: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/international-law-year-in-review/yir2018.pdf

[8] Mbengue, M. M. (2019). Africa’s voice in the formation, shaping and redesign of international investment law. ICSID Review-Foreign Investment Law Journal, 34(2), 455-481.

[9] UNCTAD Database. Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740

[10] CBE. Economic research: Economic review & monthly bulletin (different issues). Central Bank of Egypt (CBE). Retrieved from: https://www.cbe.org.eg/en/EconomicResearch/

[11] UNCTAD (2021). World Investment Report 2021: Investing in Sustainable Economy. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, USA, New York

[12] UK and Egypt sign Association Agreement: UK (2020) https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-and-egypt-sign-association-agreement

[13] Ministry of Industry and Trade Official Website. Agreements. Retrieved from: http://www.mti.gov.eg/English/Pages/agreements.aspx

[14] IMF Country Focus (2021). Egypt: Overcoming the COVID Shock and Maintaining Growth. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/07/14/na070621-egypt-overcoming-the-covid-shock-and-maintaining-growth

[15] Fadl, N. & Ghoneim,H. (2020). Impact of foreign exchange rate on foreign direct investment: Egypt case. Revue d'études sur les institutions et le développement, 6(1), 138-157.

[16] Based on Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy proclamations in a number of Egyptian newspapers, such as Masrawy and Alahram.

[17] IRENA (2018). Renewable energy outlook: Egypt. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Cairo, Egypt. Retrieved from: https:// www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Oct/IRENA_Outlook_Egypt_2018_En.pdf

[18] Based on Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy proclamations in a number of Egyptian newspapers, such as Masrawy and Alahram.

[19] OECD (2020). OECD review of foreign direct investment statistics: Egypt. OECD. www.oecd.org/investment/OECD-Review-of-Foreign-Direct-Investment-Statistics-Egypt.pdf

[20] Gafi-Home: https://www.gafi.gov.eg/English/Pages/default.aspx

[21] Arab Republic of Egypt General Authority for Investment and Free Zones . https://www.investinegypt.gov.eg/english/pages/reef.aspx

[22] Provided data is based on the official website for General Authority For Suez Canal Economic Zone

[23] Scott, E. (2013). China goes global in Egypt: A special economic zone in Suez. Discussion Paper 22. Stellenbosch University Library and Information Services: Center for Chinese studies.

[24] El-Tawil, N. (2018). Details of Egyptian-Chinese agreements, prospective partnerships . Egypt today Press. Retrieved from: https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/59533/Details-of-Egyptian-Chinese-agreements-prospective-partnerships

[25] MTS (2021). Tay Yong: Korean investments in Egypt maritime transport sector and upgrading Alex port soon. Retrieved From: https://www.emdb.gov.eg/en/content/948-Tay-Yong%3A-Korean-investments-in-Egypt-maritime-transport-.

[26] Cheong, D. (2016, October 31). Singapore firm PIL opens Egypt logistics hub. The Straits Times. Retrieved from: https://www.straitstimes.com/business/spore-firm-pil-opens-egypt-logistics-hub

.tmb-listing.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8636ce67_1)